Franklin's lost expedition facts for kids

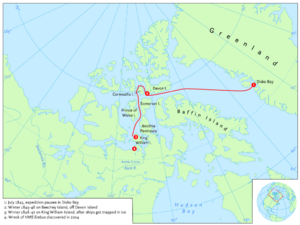

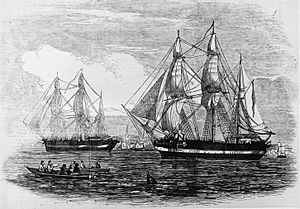

The Franklin's lost expedition was a British journey to explore the Arctic in 1845. It was led by Captain Sir John Franklin. Two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, set sail from England. Their main goal was to find the last unknown parts of the Northwest Passage in the Canadian Arctic. They also wanted to collect magnetic data to help with navigation.

Sadly, the expedition faced a terrible disaster. Both ships and all 129 officers and men got stuck in the ice near King William Island in what is now Nunavut, Canada. After being stuck for over a year, Erebus and Terror were left behind in April 1848. By then, Franklin and almost two dozen others had already died. The remaining crew, led by Francis Crozier and James Fitzjames, tried to walk to the Canadian mainland. They were never seen again and are believed to have died.

Sir John Franklin's wife, Lady Jane Franklin, and others pushed the British Navy to search for the missing expedition. Many search parties were sent out over the next few decades. They found several items from the expedition, including the remains of two men. Modern scientific studies suggest the men did not die quickly. They likely suffered from extreme cold, hunger, lead poisoning, and diseases like scurvy. Being in such a harsh environment without enough warm clothes or food led to everyone's death after 1845.

Even though the expedition failed, it helped explore the area around one of the many Northwest Passages. Robert McClure led one of the search expeditions. His journey was also very difficult. McClure's team found an ice-covered route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. This was a big discovery! The Northwest Passage was finally sailed through by boat in 1906. This was done by Roald Amundsen on his ship, the Gjøa.

In 2014, a Canadian team found the wreck of Erebus. It was in the eastern part of Queen Maud Gulf. Two years later, the Arctic Research Foundation found the wreck of Terror. It was south of King William Island, in a place now called Terror Bay. Research and dive trips happen every year at these wreck sites. They are now protected as a National Historic Site.

Contents

Ships and Supplies

The expedition used two ships: HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. Both ships had been used before for a trip to the Antarctic. Francis Crozier had commanded Terror on that earlier journey. Sir John Franklin was given command of Erebus and the whole expedition. Crozier became his second-in-command and led Terror.

The ships were very strong and well-equipped. They even had new inventions for their time. They had steam engines that powered a single screw propeller on each ship. These engines were actually converted from old steam locomotives! The ships could travel at about 7.4 kilometers per hour (4.6 mph) using steam. They could also use wind power to go faster or save fuel.

Other cool technologies on the ships included:

- Strong bows (front parts) made with heavy beams and iron plates.

- An internal steam heating system to keep the crew warm in the cold Arctic.

- A system that allowed the propellers and rudders to be pulled up into the ship's body. This protected them from ice damage.

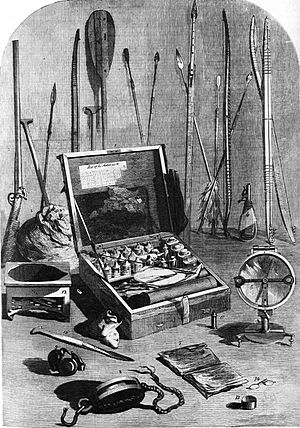

The ships also carried libraries with over 1,000 books. They had enough food for three years. This included tinned soup and vegetables, salt-cured meat, and pemmican. They even had live cattle for fresh meat. The tinned food was ordered quickly, which led to some problems. Later, it was found that some tins had lead soldering that was not done well. Most of the crew were from England, with some from Ireland, Wales, and Scotland.

Journey and Disappearance

The expedition started its journey on May 19, 1845. There were 24 officers and 110 men. The ships made a quick stop in Scotland. Then they sailed to Greenland. In Greenland, 10 oxen were killed for fresh meat. The crew also wrote their last letters home. Five men who were sick were sent back to England, leaving 129 men on the expedition.

In late July 1845, whaling ships saw Terror and Erebus in Baffin Bay. The expedition was waiting for good conditions to cross to Lancaster Sound. After this sighting, no European ever heard from the expedition again.

Most of what we know about what happened next comes from other expeditions and interviews with Inuit people over the next 150 years. The only direct information from the expedition itself is a two-part note found on King William Island.

Franklin's men spent the winter of 1845–46 on Beechey Island. Three crew members died there and were buried. In the summer of 1846, the ships sailed down Peel Sound. In September 1846, Terror and Erebus got stuck in the ice near King William Island. They are believed to have never sailed again.

The second part of the note, dated April 25, 1848, said that the crew had spent two winters stuck in the ice. It also stated that Franklin had died on June 11, 1847. The remaining crew decided to leave the ships on April 26, 1848. They planned to walk across the island and the sea ice towards the Back River on the Canadian mainland. By this time, 8 more officers and 15 men had also died. This note is the last known message from the expedition.

From things found by archaeologists, it's believed that all the remaining crew died during their long walk. Most died on King William Island. About 30 or 40 men reached the northern coast of the mainland. But they died there, still hundreds of miles from any settlements.

What We Learned from the Expedition

Mapping the Arctic

The most important result of the Franklin expedition was the mapping of thousands of miles of coastline. This mapping was done by the many expeditions that searched for Franklin's lost ships and crew. As one historian noted, losing the expedition probably led to much more geographical knowledge than if it had returned successfully.

The Northwest Passage

Franklin’s expedition explored the area around what would become one of the many Northwest Passages. While the famous search expeditions were happening in 1850, Robert McClure set out on his own journey. He commanded HMS Investigator to search for Franklin. McClure didn't find much about Franklin's fate. But he did find an ice-covered route that connected the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. This was the Prince of Wales Strait, which was far north of where Franklin's ships were.

McClure was honored for his discovery. Today, people still debate "who discovered the Northwest Passage?" This is because there are many different passages, and some are easier to sail through than others.

Simpson Strait

Some members of the Franklin expedition crossed the southern part of King William Island. They made it onto the Canadian mainland. We know this because human remains from the expedition have been found there. This journey might have involved walking across the Simpson Strait. This strait is now known as a way through from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It's possible that the Franklin expedition did discover this passage. However, since no one survived, we don't know if they realized its importance. George Back had found the strait in 1834 but didn't know it was a Northwest Passage.

The Northwest Passage was not fully sailed through by boat until 1906. That's when Roald Amundsen famously traveled through it on the Gjøa, using the Simpson Strait.

Importance in Canada

The Franklin expedition has had a big impact on Canadian literature and culture. One well-known song about it is "Northwest Passage" by the Canadian singer Stan Rogers. Some people even call it Canada's unofficial national anthem. The famous Canadian writer Margaret Atwood has called the Franklin expedition a kind of national myth for Canada. She said that some stories are told again and again in a culture, and the Franklin expedition is one of them in Canada.

Timeline of Events

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1845 | 12 May | Expedition leaves Woolwich, England. |

| At Greenhithe, crews get pay advances for their families. | ||

| 19 May | Expedition leaves Greenhithe with 134 men and some animals. | |

| 26 May | Expedition passes Sheerness. | |

| Expedition stops at Stromness, Scotland for water. Some letters are sent home. | ||

| Early July | Expedition reaches Disko Island, Greenland. Five sick men are sent home. | |

| 12 July | Expedition leaves Greenland. | |

| 26 July | Expedition is seen by whaling ships in Baffin Bay. | |

| 1845–46 | Expedition sails up Wellington Channel and returns by Cornwallis Island. | |

| Expedition spends winter on Beechey Island. | ||

| 1846 | 1 January | John Torrington dies and is buried at Beechey Island. |

| 4 January | John Hartnell dies and is buried at Beechey Island. | |

| 3 April | William Braine dies. | |

| c. 8 April | Braine is buried at Beechey Island. | |

| HMS Erebus and HMS Terror leave Beechey Island and sail down Peel Sound towards King William Island. | ||

| 12 September | Ships get stuck in the ice off King William Island. | |

| 1846–47 | Expedition spends winter on King William Island. | |

| 1847 | 28 May | A small party leaves notes at Victory Point and Gore Point, saying "All well". |

| 11 June | Franklin dies. Crozier takes charge of the expedition. | |

| 1847–48 | Expedition winters again off King William Island, as the ice doesn't melt. | |

| 1848 | 22 April | Erebus and Terror are abandoned after one year and seven months trapped in the ice. |

| 25 April | A second note is left, saying 24 men are dead, including Franklin. The 105 survivors plan to walk south to the Back River. | |

| July | Scheduled end of food supplies. | |

| Many men die at Erebus Bay and Terror Bay. Some try to return to the ships. | ||

| 1850 | 7 March | The British government offers rewards for finding the expedition. |

| 19 August | Erasmus Ommanney finds the expedition's camp on Beechey Island. | |

| 1854 | Dr. John Rae talks to local Inuit and buys items from the expedition. | |

| 1 March | The expedition members are officially declared dead. | |

| 1859 | Francis Leopold McClintock finds the 1847–48 notes, an abandoned boat, and a skeleton. | |

| 1864–69 | Charles Francis Hall searches for survivors and interviews Inuit. He finds many items. | |

| 1878–1880 | Frederick Schwatka leads a search, collects Inuit stories, and finds items and remains. | |

| 1949 | Human remains are found near a camp, possibly from graves. | |

| 1984–86 | Beechey Island graves are opened. Bodies show signs of lead poisoning. | |

| 1995 | David Woodman publishes a book with Inuit testimonies. | |

| 2014 | 7 September | Wreck of Erebus is found. |

| 2016 | 3 September | Wreck of Terror is found in Terror Bay. |

| 2020 | Archaeological work paused due to COVID-19 pandemic. | |

| 2021 | A body found in 1859 is identified by DNA as John Gregory. | |

| 2022 | May | Research at wreck sites starts again. |

| 2024 | September | Bones found in 1993 are identified by DNA as James Fitzjames. |

Images for kids

-

Captain Francis Crozier, second-in-command of the expedition, led HMS Terror.

-

Commander James Fitzjames was captain of the expedition's main ship, HMS Erebus.

-

Sonar images of the first ship found, HMS Erebus, in September 2014.

-

A statue of John Franklin in his hometown of Spilsby, England.

-

A statue of Francis Crozier in his hometown of Banbridge, Ireland.

-

An illustration by Édouard Riou for a book by Jules Verne.

-

Man Proposes, God Disposes by Edwin Landseer, 1864.

-

The four graves at Franklin Camp near the harbor on Beechey Island, Nunavut, Canada.

-

(L–R) Three grave stones for John Torrington, William Braine and John Hartnell of the Franklin Expedition. A fourth stone is for Thomas Morgan, a sailor from a later search expedition.

See also

In Spanish: Expedición perdida de Franklin para niños

In Spanish: Expedición perdida de Franklin para niños