McClure Arctic expedition facts for kids

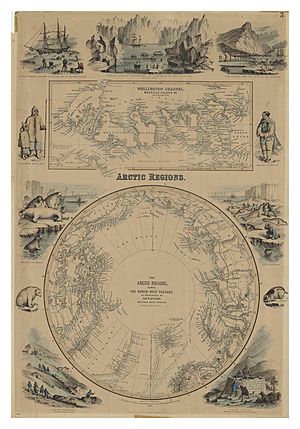

The McClure Arctic expedition started in 1850. It was one of many British efforts to find out what happened to Franklin's lost expedition. During this trip, the Irish explorer Robert McClure became the first person to prove and travel through the Northwest Passage. He did this by sailing and using sledges.

McClure and his crew spent three years stuck in the ice on their ship, HMS Investigator. They eventually had to leave their ship and escape across the ice. Another ship, HMS Resolute, rescued them. McClure returned to England in 1854. He was made a knight and rewarded for completing the passage.

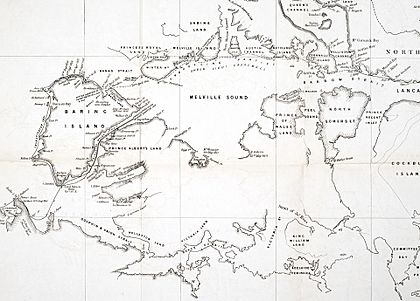

The expedition found the first known Northwest Passage, which was the Prince of Wales Strait. It also made the first journey across the Canadian Arctic from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean. However, they didn't actually sail through the Prince of Wales Strait. Instead, they crossed Banks Island, then went through Banks Strait, Melville Sound, and Barrow Strait. Finally, they entered the Atlantic Ocean through the Parry Channel. This second route was found by accident because the crew was trying to find their way back home.

Today, ships rarely travel through the Northwest Passage. It's not good for business because the ice is too unpredictable. The SS Manhattan, the first commercial ship to cross the Northwest Passage, used the Prince of Wales Strait, which McClure discovered first.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Journey

Lady Jane Franklin pushed hard for a search for the Franklin Expedition. It had been missing since 1847. McClure had served on HMS Enterprise in 1848, but that trip didn't find any trace of Franklin.

So, on January 15, 1850, the British Navy ordered a new expedition. Their main goal was to find and help Sir John Franklin. They also hoped to complete the Northwest Passage from the other direction.

Two ships were chosen for this mission. The Enterprise was sent out again with Captain Richard Collinson. Investigator was led by Commander Robert J. McClure. This was his first time commanding an Arctic expedition. Both ships needed a lot of repairs because they had already been to the Arctic. They even got a new heating system. The Investigator had a walrus figurehead and a strong engine.

They packed plenty of preserved meat. Some of it spoiled, but it didn't cause big problems. They also took extra preserved limes to prevent scurvy, a disease caused by lack of vitamin C. The plan was to sail for seven months. They would go across the Atlantic, through the Straits of Magellan, to Hawaii, and then through the Aleutian Islands to the Bering Strait. This route would get them to the Arctic when there was the least ice. The ships carried enough supplies for a three-year journey.

The Start of the Voyage

On January 10, 1850, the ships left Woolwich, England. They finished loading supplies in Plymouth on January 20. There were 66 crew members, including John Miertsching, a German clergyman who could speak Inuit. By March 5, they had crossed the equator.

They reached the Strait of Magellan on March 15. The Enterprise was always faster than the Investigator. The two ships lost contact after the strait. McClure later reported that they officially separated on February 1, 1850.

As they continued north, storms damaged about 1,000 pounds of stored biscuits. But they got fresh supplies from the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii). On June 15, the Investigator crossed the equator again. They had already traveled nearly 15,000 miles. Everyone was in good spirits. McClure wrote in his journal, "I have much confidence in them. With such a spirit what may not be expected, even if difficulties should arise?"

On July 1, they stopped in Honolulu for fresh food. They had just missed the Enterprise by one day. Five days later, McClure sailed northwest. Strong winds helped them reach the Arctic Circle on July 28. They had passed both the Enterprise and HMS Herald. The crew got busy preparing their Arctic gear to explore the Arctic alone.

Reaching the Arctic

Instead of waiting for the Enterprise, McClure made a surprising decision. He took the Investigator alone into the ice near Cape Lisburne, Alaska. On July 20, McClure sent a letter explaining his plan. He said going alone was the best way to succeed since the Enterprise had already separated.

They saw ice fields on August 2. They couldn't find open paths, so they sailed around Point Barrow, the northernmost tip of Alaska. They entered unknown waters and the first ice floes.

Meanwhile, the Enterprise arrived at Point Barrow about two weeks later. Its path was blocked by ice, so it had to turn back. It spent the winter in Hong Kong, losing a whole season. The two ships never met again. The Enterprise carried out its own Arctic explorations.

On August 8, McClure and the Investigator met some local Inuit people. They had no news of Franklin. The Inuit were surprised to see sailing ships. As they sailed along the coast east of Point Barrow, the crew left message cairns (piles of stones) at each landing spot. They sometimes traded with the Inuit but still found no news of Franklin.

Ice and shallow waters made it hard to go northwest. At one point, the Investigator got stuck so badly that all supplies had to be moved to her boats. One boat tipped over, losing 3,344 pounds of dried beef. After being freed, McClure continued northeast, moving between ice floes and open water. They reached solid pack ice on August 19.

They met more Inuit groups near Point Warren, by the Mackenzie River. One group reported a European had died. It turned out to be from an overland trip by Sir John Richardson two years earlier, not Franklin's party. The ice to the north was too thick. But by September 3, they reached Franklin Bay to the west. They saw lots of wildlife there.

After spotting Banks Island, which McClure called "Baring Land," they explored it briefly. This was probably the first time anyone had explored it. A rock formation was named Nelson Head on September 7 because it looked like Lord Nelson. They followed the coast, hoping to find a way north.

They made good progress until a wind change on September 10. The ice closed in around the Investigator just as they found a promising route, the Prince of Wales Strait. They moved slowly through the ice, sometimes using ice anchors and saws. Temperatures were around 10°F. By September 16, they reached their furthest point north. They were just short of Barrow's Strait. They took off the rudder and started preparing for winter. A year's worth of supplies were brought on deck. They worried the ship might be crushed by the ice. The dangerous drifting ice finally stopped on September 23.

The Investigator was sometimes violently pushed by the ice. It stayed just south of Princess Royal Island. The ice became calmer by September 27, 1850. On the last day of September, the temperature dropped below 0°F for the first time. They took down the top masts for winter. McClure noted, "The crushing, creaking, and straining are beyond description." The ship was lifted several feet. They used black powder to blast away ice hummocks that threatened the ship.

They made several trips across the ice to land. McClure was sure there was a Northwest Passage. In mid-October, they officially claimed Prince Albert's Land and nearby islands. The crew started their winter routines, including lessons in reading, writing, and math. Hunting was difficult, but they caught five musk oxen. This helped stretch their food supplies.

The Northwest Passage Confirmed

On October 21, 1850, Captain McClure went on a sledge trip with seven men. They went northeast to confirm his ideas about the Northwest Passage. McClure confirmed it when he returned on October 31. He had seen a clear strait leading to Melville Island from a 600-foot peak on Banks Island. The ship's log entry read:

"October 31st, the Captain returned at 8.30. A.M., and at 11.30. A.M., the remainder of the parting, having, upon the 26th instant, ascertained that the waters we are now in communicate with those of Barrow Strait, the north-eastern limit being in latitude 73°31′, N. longitude 114°39′, W. thus establishing the existence of a NORTH-WEST PASSAGE between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans."

First Winter and Summer

The sun disappeared on November 11. Temperatures averaged -10°F, but it was 48°F below deck. The crew was healthy. They kept the air clean by increasing ventilation. The new year was celebrated. The crew entertained themselves, sometimes catching foxes or seeing seals. Winter temperatures averaged -37°F. On February 3, the sun returned after 83 days of darkness.

They set up an emergency supply depot and left a whaleboat on a nearby island. They saw reindeer, Arctic foxes, hares, ravens, wolves, and a polar bear. Local expeditions started again.

As spring returned, they cleared snow from the Investigator's decks and began repairs. More local trips were made. By mid-May, more hunting and exploration parties went out to find food. Some returned with frostbite. One party met isolated Inuit seal hunters. One group went around Banks Island and proved it was an island. Another party was on the south shore of Victoria Island. No signs of Franklin were found. As summer returned, the seven-foot-thick ice started to melt. An early breakup was expected.

They prepared for the ship to be freed from the ice. In late June, temperatures reached 53°F. But the ice held the Investigator until July 14. Then, the ship was finally sailing again near the Princess Royal Islands. They made progress northward. There was even hope of completing the passage that year. However, in August, progress slowed to a crawl. The solid northern ice offered few chances to move forward. On August 14, they reached their northernmost point in the Prince of Wales Strait. Some thought that if the Investigator had a propeller, it could have gone the 45 miles to Melville Island, finished the Northwest Passage, and returned home that year.

They decided to leave the strait and go around the south coast of Baring Island (Banks Island). This led them to open water and a wider search area. They continued through loose ice until they had to tie the ship to an iceberg for safety. They explored the nearby coast. They found old Inuit camps and petrified wood from an ancient forest. As winter returned, the ice threatened them several times while they were still attached to the iceberg. The crew managed these problems, often by blasting the ice. But McClure chose not to leave the iceberg for nearby open water, missing several chances.

Second Winter and Summer in Mercy Bay

Later efforts to move the ship eastward were slow. But occasional open water helped them get closer to Melville Island. Instead of following the ice east, McClure chose to take shelter in an open bay. On September 23, the ice stopped their progress. The ship was prepared for a second winter. Some crew members thought entering this bay was a big mistake. The expedition surgeon, Armstrong, said, "entering this bay was the fatal error of our voyage." The ice would have taken them within 50 miles of Melville Island. This would have given them a better chance of breaking free early in the spring. Their winter location was named Mercy Bay.

Their food supplies were running low. By October, heating was cut back until the coldest parts of winter. Temperatures below deck were around -10°F. Hunting parties were usually successful. But their explorations frustratingly showed open water just 8 miles outside Mercy Bay. As winter continued, the weakening hunting parties often needed rescue. On November 10, the ship was sealed for the winter. The crew made needed items and used gun wadding as money. Boredom was severe. Two crewmen even went temporarily mad. In December, storms came as temperatures kept falling.

The new year began with the crew generally healthy. This was mostly thanks to the reindeer venison provided by hunters. Temperatures reached -51°F. Frequent hunting of nearby reindeer continued to add to their food. But the hunters suffered from the cold and sometimes needed rescue. Despite fresh meat, the crew slowly grew weaker. Of all the ships searching for Franklin the previous year, only the Enterprise and Investigator remained in the Arctic, separated.

On April 11, McClure led seven men by sledge with 28 days of food. They hoped to reach Melville Island across the ice and find other British explorers. In late April, the first case of scurvy appeared, with more soon after. McClure's party returned on May 7. They said poor visibility and soft snow had made progress difficult. They didn't reach Melville Island. But they saw enough of the strait and a large harbor to know that Captain Austin's ships were not there. They did find a cairn left by Sir Edward Parry from his 1819–1820 expedition. It also had a message from Captain Austin from June 1851. This message did not say that traces of Franklin's expedition had been found the previous year at Beechey Island.

In June, the crews prepared to be freed from the ice of Mercy Bay. Temperatures rose, but it was cooler than the year before. Cases of scurvy kept increasing. But hunting and gathering sorrel (a plant) helped. By mid-June, the ice outside the bay was moving. By September, all hope of freeing the ship was gone. McClure planned to abandon the ship in the spring. He wrote that "nothing but the most urgent necessity will induce me to take such a step."

The Third Winter

On September 8, McClure announced his plan for escaping in the spring. Twenty-six crew members would go to Cape Spencer (550 miles away). Austin had left supplies and a boat there. From there, they would seek rescue on Baffin Bay. A smaller group of eight men would go back along the shore of Banks Land. They would go to the supplies and boat McClure had left in 1851. Then they would head to the Hudson's Bay Company post on the Mackenzie River for rescue. This plan would stretch the food for the crew staying on the Investigator. Food rations were immediately cut. Hunting success became even more important. They even started hunting mice.

In October, the crew's health continued to get worse. This winter was the coldest yet. The ship was prepared for winter. Temperatures below deck were below freezing. Complete darkness returned on November 7. Morale and physical activity, including hunting, decreased. The officers continued hunting, often needing rescue as temperatures reached -65°F. 1852 ended with the crew weaker and sicker than ever before. But not a single crew member had been lost.

1853 brought the coldest conditions yet, once reaching -67°F. The crew spent their days with minimal activity. They worked on small necessary projects and hunted when possible. Rations were thin, and the sick bay was full. Even minor illnesses caused big problems for the weakened crew. McClure continued preparing his spring escape parties. He planned to send the weaker but able men to improve the chances of those left behind. Crew selections were made and announced on March 3. Full rations were given to the men preparing to leave in mid-April, and their health improved. Still, on April 5, the first crew member, John Boyle, died. This affected morale and showed how serious their situation was.

Relief and the Fourth Winter

Preparations for the escape parties continued, despite their slim chances. On April 6, men digging Boyle's grave saw a figure approaching from the sea. It was Lieutenant Bedford Pim of HMS Resolute. The Resolute was spending the winter off Melville Island with Captain Henry Kellett. It was 28 days away by sledge. The Resolute was with Intrepid, laying supply depots for the continued search for Franklin and now McClure. Pim had found one of McClure's hidden messages from 1852. Pim later described meeting McClure:

"Who are you, and where (did) you come from?"

"Lieutenant Pim, Herald, Capt. Kellett." This was more inexplicable to M'Clure, as I was the last person he shook hands with in Behring's Straits.

Two days later, Pim left for the Resolute, about 80 miles east. McClure and six men soon followed him. They would journey for 16 days.

Despite the good news of relief, conditions on the Investigator were still getting worse. Scurvy increased with the reduced rations. On April 11, another crewman died, and another the next day. Some exercise was possible for the crew. Breathing was helped by the modern Jeffreys respirator.

On April 15, the 28-man traveling party, now focused only on Melville Island, set out on three sledges. Four days later, McClure reached the ships and met with Captain Kellett and Commander McClintock. McClure returned on May 19 with Dr. W. T. Domville, the surgeon from the Resolute. A medical survey was done to see if the Investigator could be properly manned if freed from the ice. The assessment showed it couldn't. It was "utterly unfit to undergo the rigour of another winter in this climate." This made abandoning the Investigator unavoidable. Captain Kellett of the Resolute ordered it. The official announcement was made. All men were put back on full rations for the first time in 20 months. A beach supply depot was set up by the end of May, with a cairn and a monument to the fallen crew members.

On June 3, final flags were raised. The remaining crew left the Investigator. They traveled by sledge to the Resolute. They had 18 days of supplies. McClure led the way on foot. Progress across the melting ice was slow. The four sledges weighed between 1,200 and 1,400 pounds. The weakened crew reached Melville Island on June 12 and the ships on June 17.

A group of sick men had been taken from the Resolute to Beechey Island and North Star. They were sent back to England in October 1853. This was the first news of the Investigator and the Northwest Passage to reach the outside world. Hunting helped with food while the Resolute and Intrepid waited to be freed from the ice. The ice broke up on August 18. The ships followed the edge of the ice before getting stuck again in early November. The combined crews prepared for another winter in the ice. Another crewman died on October 16. Far from shore, they couldn't hunt effectively. 1854 began the fifth year of Arctic service for the Investigator's crew.

Escape and Return Home

Plans were made to move the Investigator's crew to the North Star at Beechey Island in the spring of 1854. These three sledge parties set out on April 10–12. The journey was tough, but the crews were in better condition. Socks often froze to their feet and had to be cut off to fight frostbite. Despite these hard conditions, the parties reached the North Star between April 23–27. Even with this relief, another man died at Beechey Island. They searched the area for more signs of Franklin. Beechey Island was known to be his first winter camp. Meanwhile, the Resolute and Intrepid were also abandoned. Their crews joined the Beechey Island camp on May 28.

An exploration party from the Resolute had earlier met Captain Collinson and the Enterprise. They learned about their search path. A report on the Investigator's condition, abandoned for about 12 months, was also obtained. It said the ship was damaged and leaking but otherwise whole and held by the ice. Mercy Bay was still solid. By mid-August, the North Star was freed from the ice. Two other nearby ships were abandoned on August 25. They sailed along Greenland and reached the English port of Ramsgate on October 6, 1854. They had been gone for four years and ten months and lost five men.

Ship Found

In July 2010, Parks Canada archeologists were looking for HMS Investigator. They found it just fifteen minutes after starting a sonar scan of Banks Island, Mercy Bay, Northwest Territories. The archaeology team said they had no plans to raise the ship. Instead, they planned a full sonar scan of the area and would send a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). Parks Canada archeologists planned dives on the Investigator site for 15 days starting on July 10, 2011. They wanted to get detailed photos of the wreck. Led by Marc-Andre Bernier, the team of six divers were the first to visit the wreck. It lies partly buried in silt just 150 feet off the north shore of Banks Island.

What McClure's Journey Taught Us

McClure is known as the first person to complete the Northwest Passage (by boat and sledge). He was given a share of the £10,000 prize for completing the passage.

Later, the Copper Inuit people salvaged metals and materials from the abandoned Investigator. This was a big change in how they used materials.

The McClure Strait is named after Captain McClure.

On October 29, 2009, a special service was held in Greenwich. It was to honor the national monument to Sir John Franklin. The service also included burying the remains of Lieutenant Henry Thomas Dundas Le Vesconte. He was the only crew member whose remains were brought back to England. This event brought together polar explorers, photographers, authors, and many descendants of Franklin and his search parties. It celebrated the United Kingdom's role in mapping the Canadian North. It also honored the lives lost in exploring new places.

How McClure's Trip Was Different from Franklin's

- McClure used an Inuit interpreter. Franklin's expedition had no interpreters or Inuit people. Their knowledge of the area might have helped Franklin's crew survive.

- Banks Island had enough game (animals to hunt). This helped McClure's crew avoid severe scurvy and weakness. Franklin's crew seemed to have a much harder time. The game near Beechey Island was less common. This lack of fresh food, plus spoiled canned provisions, hurt Franklin's expedition.

- McClure benefited from leaving message cairns (stone piles) along his route. One of these was found by the Resolute, which led directly to their rescue. Franklin only left two message cairns, even though he had many message canisters. More messages from Franklin would have helped search efforts. Many searchers guessed his route incorrectly.