History of Ontario facts for kids

The history of Ontario covers the time from when the first people arrived thousands of years ago until today. The land that is now Ontario, Canada's most populated province, has been home to Indigenous groups for a very long time. French and British explorers and settlers started arriving in the 1600s. Before Europeans, the area was home to Algonquian tribes like the Ojibwa, Cree, and Algonquin, and Iroquoian tribes like the Iroquois, Petun, and Huron.

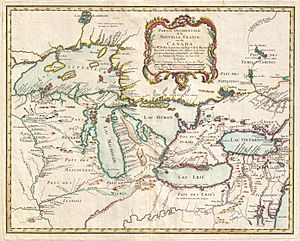

French explorer Étienne Brûlé explored parts of the area between 1610 and 1612. The English explorer Henry Hudson sailed into Hudson Bay in 1611 and claimed the land for England. Later, Samuel de Champlain reached Lake Huron in 1615. Both the English/British and the French built fur trading forts in Ontario during the 1600s and 1700s. They wanted to control the North American fur trade. The English built forts around Hudson Bay, while the French built forts in the Pays d'en Haut region.

The two sides fought over the area until the end of the Seven Years' War. In 1763, the Treaty of Paris gave the French colony of New France to the British.

After the American Revolutionary War, many loyalists (people who supported Britain) moved to the area. Because of this, the Constitutional Act of 1791 was passed. It split the colony of Quebec into Lower Canada (now southern Quebec) and Upper Canada (now southern Ontario). These two areas were later reunited as the Province of Canada by the Act of Union 1840.

On July 1, 1867, the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia joined together to form a new country called Canada. The Province of Canada was then split into two provinces: Quebec (east of the Ottawa River) and Ontario (west of the river).

Early People in Ontario

Woodland Period Life

The Woodland period came after the Archaic period. During this time, people started using ceramics (pottery). They also began trying to grow different crops, especially maize (corn). Later in this period, people started building villages and farming.

Farming mostly happened in southern Ontario. However, northern Ontario saw big changes in pottery and continued building mounds. Pictographs (rock paintings) were made during the Late Woodland period. People continued to make them even after Europeans arrived, sometimes showing horses, guns, and ships.

By the later part of the Woodland period, many different Indigenous groups lived in the area. Some of these groups formed powerful alliances. In what is now Ontario, examples include the Huron, Petun, and Neutral confederacies. These Northern Iroquoian peoples were related to the Iroquois Confederacy further south. The land was also home to Algonquian peoples like the Ojibwe, Cree, and Algonquin.

French and British Exploration

French explorer Étienne Brûlé explored parts of the area in 1610–1612. The English explorer Henry Hudson sailed into Hudson Bay in 1611 and claimed the land for England. But Samuel de Champlain reached Lake Huron in 1615.

French Jesuit missionaries set up posts along the Great Lakes. They made alliances, especially with the Huron people. However, permanent French settlement was difficult because of conflicts with the Five Nations of the Iroquois, who were allied with the British. By the 1650s, the Iroquois, using British and Dutch weapons, pushed other Iroquoian-speaking groups like the Petun and Neutral Nation out of southern Ontario.

In 1747, a small group of French settlers started the oldest continuously inhabited European community in what became western Ontario. This place, called Petite Côte, was settled on the south bank of the Detroit River, near Huron and Petun villages. The British also set up trading posts on Hudson Bay in the late 1600s.

British Rule and New Beginnings

Province of Quebec (1763–1791)

After winning the Seven Years' War, Britain gained almost all of France's North American lands (New France) through the 1763 Treaty of Paris. Areas like Canada and the Pays d'en Haut were combined and renamed the Province of Quebec.

The first English settlements in what is now Ontario happened in 1782–1784. About 5,000 American loyalists fled the American Revolution and settled in places like the Thousand Islands and the Niagara Peninsula. From 1783 to 1796, Britain gave these families land and other supplies to help them rebuild their lives.

Upper Canada (1791–1841)

The Constitutional Act of 1791 recognized this growth. It split the Province of Quebec into the Canadas. Lower Canada was east of the St. Lawrence-Ottawa River, where settlement first began. Upper Canada was southwest of this area. John Graves Simcoe became Upper Canada's first Lieutenant-Governor in 1793.

War of 1812

The United States declared war on the United Kingdom on July 1, 1812. This was partly because the British were taking American sailors and were thought to be supporting Native Americans in the Northwest Territory. Because it was so close to the United States, Upper Canada became a major battleground.

Early fights happened near southwestern Ontario and the Great Lakes. American forces briefly entered Ontario. Then, British and First Nations forces attacked into the Michigan Territory. However, in September 1813, the Americans gained control of Lake Erie. British forces left Detroit and decided to retreat. American forces, led by William Henry Harrison, caught up to them and defeated them at the Battle of the Thames. Tecumseh, a leader of a Native American alliance, was killed. This broke the alliance between the British and First Nations.

American forces also tried to invade the Niagara Peninsula several times. On October 13, 1812, an American invasion was stopped at the Battle of Queenston Heights. However, Major-General Isaac Brock, the British commander, was killed. On April 27, 1813, American forces raided and briefly took over York, the capital of Upper Canada. A month later, Americans captured Fort George, forcing the British to retreat. But American advances were stopped at the Battle of Stoney Creek and Battle of Beaver Dams. The Americans eventually left the peninsula in December 1813. An American invasion force heading towards Montreal was also defeated at the Battle of Chrysler's Farm in November 1813.

In the summer of 1814, Americans invaded the Niagara Peninsula again, defeating the British at the Battle of Chippewa. However, American forces had to retreat to Fort Erie after the Battle of Lundy's Lane on July 25, 1814. Americans held off a British siege of the fort, but they left the fort in November 1814. American actions in Upper Canada, like the burning of York and the raid on Port Dover, later led to British forces burning Buffalo and Washington. The war ended in December 1814 with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent.

Transportation and Growth

After the War of 1812, things became more stable. More immigrants came from Britain and Ireland, rather than the United States. Many new arrivals found frontier life hard, but the population grew a lot.

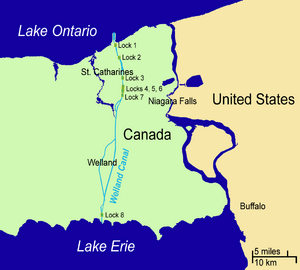

Canals and new plank roads helped trade grow within the colony and with the United States. Ontario's many waterways made travel easier and provided power for development. Canals were big projects that helped trade. The Oswego Canal in New York (built 1825–1829) was an important link to the Great Lakes–Atlantic seaway. It connected to Ontario's Welland Canal in 1829. This new route offered another way to reach the St. Lawrence River and Europe.

The Family Compact

Upper Canada was run by a small, powerful group of men from the 1810s to the 1830s. They controlled most of the political, legal, and economic power. Their opponents called them the "Family Compact." A key leader was John Strachan, the Anglican bishop of Toronto. This group was conservative and against democracy. They believed they and their militia had stopped American attempts to take over Canada in the War of 1812. They were based in Toronto and helped promote canals and railroads.

Upper Canada Rebellion

Many people were unhappy with the anti-democratic Family Compact because they controlled the best lands and power through their connections. This led to ideas of self-rule and early Canadian nationalism. Rebellions for responsible government broke out in both Upper and Lower Canada. William Lyon Mackenzie led the Upper Canada Rebellion. The rebellions failed, but they led to important changes.

Canada West (1841–1867)

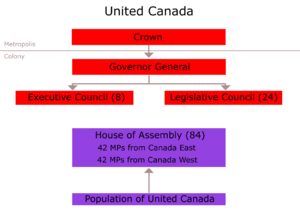

Even though the rebellions were quickly stopped, the British government sent Lord Durham to find out why they happened. He suggested that the colonies should have self-government. He also recommended that Lower and Upper Canada be joined to try and make French Canadians more like the English.

So, the two colonies were merged into the Province of Canada by the Act of Union (1840). The capital was in Kingston, and Upper Canada became known as Canada West. The colony gained parliamentary self-government in 1848.

Because of many immigrants in the 1840s, the population of Canada West more than doubled by 1851. For the first time, the English-speaking population of Canada West was larger than the French-speaking population of Canada East. This changed the balance of power.

An economic boom in the 1850s, helped by a free trade agreement with the United States, led to huge railway expansion. This made Central Canada even stronger economically before Confederation.

Confederation and the Late 1800s

A political deadlock between French- and English-speaking lawmakers, and fear of attack from the United States during the American Civil War, led leaders to hold meetings in the 1860s. They wanted to create a larger federal union of all British North American colonies.

The British North America Act (BNA Act) became law on July 1, 1867. It created the Dominion of Canada with four provinces: Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, and Ontario. The Province of Canada was divided into Ontario and Quebec so that each main European language group would have its own province.

Both Quebec and Ontario had to protect the existing educational rights of Protestant and Catholic minorities. So, separate Catholic schools were allowed in Ontario. Toronto officially became Ontario's provincial capital.

Once it became a province, Ontario started to use its economic and law-making power. In 1872, Oliver Mowat, a Liberal leader, became premier. He stayed premier until 1896. Mowat fought for provincial rights, which meant he wanted the provinces to have more power than the federal government. He often won these battles, which made Canada more decentralized.

Mowat strengthened Ontario's schools and provincial organizations. He created districts in Northern Ontario. He also fought hard to make sure that parts of Northwestern Ontario became part of Ontario. This victory was confirmed in the Canada (Ontario Boundary) Act, 1889. He also oversaw Ontario becoming Canada's economic powerhouse.

The border between Ontario and Manitoba was a big issue. The federal government tried to extend Manitoba's land eastward into areas Ontario claimed. In 1882, Premier Mowat threatened to pull Ontario out of Confederation over this. Both Ontario and Manitoba sent police into the disputed area. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain, which was Canada's highest court, sided with provincial rights. These decisions made the central government less powerful and created a more decentralized country.

Economic Development

Transportation and Industry

As the population grew, so did industries and transportation. By the end of the 1800s, Ontario was competing with Quebec as the leader in population, industry, and communication.

Ontario's manufacturing and finance sectors became very profitable in the late 1800s. New markets opened up across Canada thanks to the federal government's high-tariff National Policy after 1879. This policy limited competition from the United States. New markets in the west opened after the Canadian Pacific Railway was built (1875–1885) through Northern Ontario to the Prairies and British Columbia. Many European immigrants and Canadians moved west along the railway to get land and start farms. They shipped their wheat east and bought goods from Ontario merchants.

Farming and Innovation

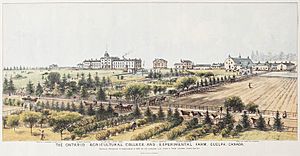

Farming was generally very profitable, especially after 1896. Big changes included using machines and focusing on high-profit products like milk, eggs, and vegetables for growing city markets. Farmers wanted more information on the best farming methods. This led to farm magazines and agricultural fairs. In 1868, the government created an agricultural museum, which became the Ontario Agricultural College in Guelph in 1874.

Commercial wine production in Ontario started in the 1860s. An aristocrat from France, Count Justin McCarthy De Courtenay, found that the right grapes could grow in the cold climate. He made an inexpensive good wine that could be sold. His success encouraged others to start wine businesses.

20th Century Ontario

In 1912, Regulation 17 was introduced by the Ontario government. It aimed to close French-language schools at a time when French speakers from Quebec were moving into eastern Ontario. The rule severely limited French-language teaching for the province's French-speaking minority. French could only be used in the first two years of school. After that, students and teachers had to use English. Many French-language teachers were not fluent in English, so schools had to close. French Canadians were very angry. The government repealed Regulation 17 in 1927. Ontario does not have an official language, but English is the main language. Many French language services are available in certain areas under the French Language Services Act of 1990.

World War I (1914–1918)

People of British background strongly supported World War I with soldiers, money, and excitement. However, French Canadians changed their support in 1915. Because Germany was an enemy, the Canadian government was suspicious of German-descent residents. Anti-German feelings grew. The City of Berlin, Ontario, was renamed Kitchener after a British commander.

The 1920s and 1930s

In 1919, the Conservatives were replaced by a new farmer's party, the United Farmers of Ontario. They formed a government with the "Ontario Independent Labour Party." They chose Ernest Drury as premier. They enforced prohibition (banning alcohol), passed a mother's pension, and set a minimum wage. The farmers and unionists did not get along well. In the 1923 election, the Conservatives won again, and George Howard Ferguson became premier.

When health surveys showed high infant death rates, especially in rural areas, the government and health reformers worked together. They started campaigns to teach mothers how to improve the lives of babies and young children.

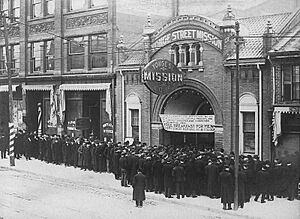

The Great Depression (1929–1939)

Farming and industry suffered during the Great Depression in Canada. Lumber regions, car plants, and steel mills were hit hardest. The milk industry faced price wars. The government set up the Ontario Milk Control Board (MCB), which raised and stabilized prices. This helped the industry, but consumers complained about higher prices.

After a big loss in 1934, the Conservatives reorganized. They focused on state help to deal with the Depression and encourage economic growth. They supported comprehensive health care and pension programs. These changes helped them win many elections from 1943 onwards.

Late 20th Century Ontario

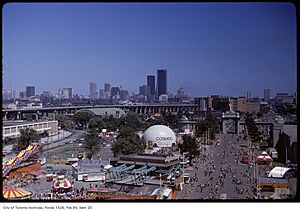

After World War II, Ontario's population grew even more. The Greater Toronto Area became the main destination for immigrants to Canada. In the 1950s and 1960s, many immigrants came from Europe. After changes to federal immigration law in 1967, most immigrants came from Asia. Ontario changed from being mostly British to very diverse.

Toronto replaced Montreal as Canada's main business center. This happened partly because the nationalist movement in Quebec, especially the success of the Parti Québécois in 1976, caused English-speaking businesses to leave. Poor economic conditions in the Maritime Provinces also led many people to move to Ontario in the 1900s.

Politics and Social Change

The Ontario Progressive Conservative Party held power in Ontario from 1943 until 1985. They stayed in the political middle ground.

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which became the New Democratic Party (NDP) in 1961, struggled after the war. Their best result was in 1948 when they became the official opposition. The NDP usually got about 20% of the vote. In a surprise win in 1990, the NDP won 38% of the vote and formed a government under Bob Rae. However, Ontario's labour unions, who supported the NDP, were angry when Rae cut pay for public workers. The NDP was defeated in 1995.

Ontario's Fair Employment Practices Act fought against racism and religious discrimination after World War II. However, it did not cover gender issues. After lobbying by women and unions, the Conservative government passed the Female Employees Fair Remuneration Act in 1951. This law required equal pay for women who did the same work as men.

Conservation and Economy

Early efforts to protect natural resources began with the Public Parks Act in 1883, which called for public parks in every town and city. Algonquin Provincial Park, the first provincial park, was created in 1893.

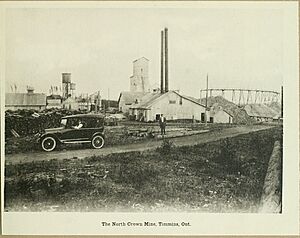

Mineral mining grew quickly in the late 1800s. This led to important mining centers in the northeast like Sudbury, Cobalt, and Timmins.

Energy policy focused on hydro-electric power. This led to the creation of the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario (HEPC) in 1906, later renamed Ontario Hydro in 1974. HEPC bought electricity from Niagara Falls and built an integrated power network. Cheap electricity helped industries grow. The Ford Motor Company of Canada was established in 1904, and General Motors Canada was formed in 1918. The car industry became Ontario's most productive industry by 1920.

Modernization and Medicine

Legal and Police Reform

Building roads and canals needed many workers. Their wages often went to alcohol, gambling, and other activities that caused fights. Community leaders realized that traditional ways of dealing with problems were not enough. They started to use more modern police, trial, and punishment systems.

Cities like Toronto, Hamilton, and Windsor modernized their public services in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The police force changed a lot. Emergency telephone call boxes, bicycles, motorcycles, and cars changed how police worked. After 1930, police radios made response times even faster.

Medical Advances

Doctors in Ontario worked to improve the quality of medical education. They banned untrained practitioners. In the 1880s, the Toronto School of Medicine (TSM) added instructors and focused on clinical teaching. In 1887, the TSM became the medical faculty of the University of Toronto, focusing more on research. In 1923, University of Toronto researchers John Macleod and Frederick Banting won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for discovering insulin in 1921. This put Toronto on the world map for science.

Transportation Changes

The fast spread of cars after 1910 and the building of roads, especially after 1920, made it easier for people in remote areas to travel to towns and cities. City people moved to suburbs. By the 1920s, it was common for city people to have a vacation cottage in remote lake areas. A part of the Queen Elizabeth Way ("QEW") opened in 1939. It was one of the world's first controlled-access highways. The trend of city dwellers having vacation cottages grew even more after 1945. This brought new money to remote areas, but also caused some environmental problems and occasional conflicts between cottagers and permanent residents.

21st Century Ontario

From the late 1900s to the early 2000s, Ontario received the largest number of immigrants in its history. Many of these immigrants settled in Toronto and Brampton. From 2020 to 2021, Ontario's government and people dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Historical Population

| Ontario | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1851 | 952,004 | — |

| 1861 | 1,396,091 | +46.6% |

| 1871 | 1,620,851 | +16.1% |

| 1881 | 1,926,922 | +18.9% |

| 1891 | 2,114,321 | +9.7% |

| 1901 | 2,182,947 | +3.2% |

| 1911 | 2,527,292 | +15.8% |

| 1921 | 2,933,662 | +16.1% |

| 1931 | 3,431,683 | +17.0% |

| 1941 | 3,787,655 | +10.4% |

| 1951 | 4,597,542 | +21.4% |

| 1961 | 6,236,092 | +35.6% |

| 1971 | 7,703,105 | +23.5% |

| 1981 | 8,625,107 | +12.0% |

| 1991 | 10,084,885 | +16.9% |

| 2001 | 11,410,046 | +13.1% |

| 2011 | 12,851,821 | +12.6% |

| Source: Statistics Canada website Censuses of Canada 1851 to 2011. | ||

See also

- Timeline of Ontario history

- Cobalt silver rush

- Porcupine Gold Rush

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |