Frederick Banting facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

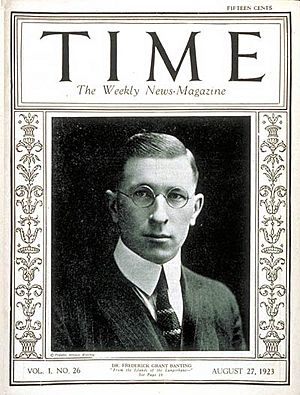

Frederick Banting

|

|

|---|---|

Frederick Banting

|

|

| Born | November 14, 1891 |

| Died | February 21, 1941 |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Alma mater | University of Toronto |

| Known for | Insulin |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1923) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Institutions | University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada |

Sir Frederick Grant Banting (November 14, 1891 – February 21, 1941) was a Canadian medical scientist and doctor. He was also a painter and a Nobel laureate. He is famous for helping to discover insulin and showing how it could be used to treat people.

In 1923, Banting and John James Rickard Macleod won the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Banting shared his prize money with his helper, Charles Best. Macleod shared his prize money with James Collip. Banting was only 32 years old when he won, making him the youngest Nobel winner in Physiology or Medicine. The Canadian government gave him money for life to keep doing his important research. In 1934, King George V made him a knight.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Frederick Banting was born on November 14, 1891, on a farm near Alliston, Ontario. He was the youngest of five children. He went to high school in Alliston. In 1910, he started studying arts at Victoria College, part of the University of Toronto.

After a tough first year, he decided to study medicine in 1912. He started medical school in September 1912.

Serving in the War

In 1915, Banting joined the army. He trained during the summer and then went back to school. His medical class finished quickly so more doctors could help in the war. He graduated in December 1916 and started military duty the very next day.

In 1918, he was hurt during the Battle of Cambrai. Even though he was injured, he helped other wounded soldiers for 16 hours! For his bravery, he received the Military Cross in 1919. In 1918, he also got his license to practice medicine.

After the war, Banting returned to Canada. He finished his training to become a surgeon in Toronto. From 1919 to 1920, he worked as a resident surgeon at The Hospital for Sick Children. He then moved to London, Ontario, to open his own medical office. His practice was not very busy, so he also taught part-time at the University of Western Ontario. In 1922, he earned his M.D. degree and a gold medal.

Discovering Insulin

A New Idea for Diabetes

Banting became very interested in diabetes after reading an article about the pancreas. He had to give a talk about the pancreas to his class in November 1920. He learned that diabetes happens when the body doesn't make enough of a special protein called "insulin." Insulin helps control sugar in the blood. Without it, sugar builds up and leaves the body in urine.

Scientists had tried to get insulin from the pancreas, but it didn't work. This was because other chemicals in the pancreas destroyed the insulin. Banting needed to find a way to get insulin without it being destroyed.

He read about a method where a tube in the pancreas was tied off. This made the cells that destroy insulin die, but it left the insulin-making cells (called islets of Langerhans) unharmed. Banting realized that after these destroying cells died, he could get insulin from the pancreas.

Working with Others

Banting talked about his idea with J. J. R. Macleod, a professor at the University of Toronto. Macleod gave Banting a lab and the help of one of his students, Charles Best. Banting and Best, along with a chemist named James Collip, started working to produce insulin.

At first, they got insulin from dogs. But they needed more. In November 1921, Banting thought of getting insulin from the pancreas of unborn calves. He found that this insulin worked just as well. By December 1921, he could also get insulin from adult pig and cow pancreases. For many years, pig and cow insulin were the main sources for treating diabetes.

On January 11, 1922, the very first insulin injection was given to a 14-year-old Canadian boy named Leonard Thompson at Toronto General Hospital. In the spring of 1922, Banting started treating diabetic patients in Toronto. One of his first American patients was Elizabeth Hughes Gossett, whose father was a U.S. Secretary of State.

Banting and Macleod won the 1923 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine together. Banting shared his prize money with Best, and Macleod shared his with Collip.

Later Research and Legacy

After the discovery of insulin, Banting became a senior teacher at the University of Toronto in 1922. The next year, he was given a special research position, funded by the government. He also worked as a doctor at several hospitals in Toronto.

At the Banting and Best Institute, he studied other health problems. He researched lung diseases like silicosis, cancer, and how drowning affects the body.

Aviation Medicine

In 1938, Banting became interested in aviation medicine. This field looks at how flying affects pilots. He worked with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) to study problems pilots faced when flying high-altitude planes. He led a special research unit for the RCAF in Toronto.

During World War II, he studied issues like "blackout," which is when pilots temporarily lose their vision or consciousness during fast turns or dives. He helped invent the G-suit, which stops pilots from blacking out due to strong g-forces. Banting also worked on how to treat mustard gas burns. He even tested the gas and antidotes on himself to see if they worked.

Personal Life and Death

Banting was married twice. His first marriage was to Marion Robertson in 1924. They had one child, William. They divorced in 1932. Banting then married Henrietta Ball in 1937.

In February 1941, Banting died in a plane crash in Musgrave Harbour, Newfoundland. He was a passenger on a Lockheed L-14 Super Electra plane. Both of the plane's engines failed after it left Gander, Newfoundland. The navigator and co-pilot died right away. Banting and the pilot, Captain Joseph Mackey, survived the crash itself. According to Mackey, Banting died from his injuries the next day. Banting was on his way to England to test the Franks flying suit.

Banting and his wife are buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto.

Images for kids

-

A. Y. Jackson and Banting on the SS Beothic, 1927

See also

In Spanish: Frederick Grant Banting para niños

In Spanish: Frederick Grant Banting para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |