John Macleod (physiologist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Macleod

FRS FRSE

|

|

|---|---|

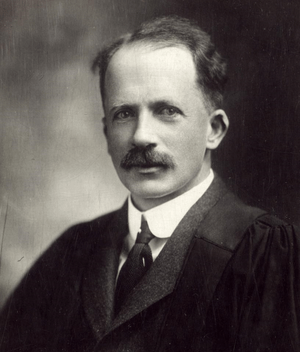

John Macleod c. 1928

|

|

| Born | 6 September 1876 Clunie, Perthshire, Scotland

|

| Died | 16 March 1935 (aged 58) Aberdeen, Scotland

|

| Alma mater | University of Aberdeen |

| Known for | Co-discovery of insulin |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1923) Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh (1923) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Institutions | Case Western Reserve University University of Toronto University of Aberdeen |

John James Rickard Macleod (September 6, 1876 – March 16, 1935) was a Scottish scientist who studied how living things work (a biochemist and physiologist). He spent his career researching many topics in science, but he was most interested in how our bodies use sugars and starches.

Macleod is well-known for his important part in discovering and isolating insulin. This happened while he was a teacher at the University of Toronto. Because of this discovery, he and Frederick Banting received the 1923 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. At the time, giving the prize to Macleod caused some debate. This was because, according to Banting, Macleod's role in the discovery was small. However, many years later, an independent review showed that Macleod's contribution was much greater than first thought.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Macleod was born in Clunie, a small place near Dunkeld in Perthshire, Scotland. Soon after he was born, his father, Robert Macleod, who was a clergyman, moved the family to Aberdeen.

In Aberdeen, John went to Aberdeen Grammar School. Later, he began studying medicine at the University of Aberdeen. One of his main teachers there was a young professor named John Alexander MacWilliam. Macleod earned his medical degree with honors in 1898.

After that, he spent a year studying biochemistry in Germany at the University of Leipzig. He did this with a special scholarship. When he came back to Britain, he became a demonstrator at the London Hospital Medical School. In 1902, he became a lecturer in biochemistry there. In the same year, he earned another degree in public health from Cambridge University. Around this time, he published his first research paper about the amount of phosphorus in muscles.

Career and Research Focus

In 1903, Macleod moved to the United States. He became a lecturer in physiology at Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. He stayed there for 15 years. During this time, he became very interested in how the body uses carbohydrates, which became his main research focus.

In 1910, he gave a talk about different types of diabetes. He explained how these studies could help understand diabetes mellitus, which is the common form of diabetes. In 1916, he became a Professor of Physiology at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

After World War I, Macleod started teaching physiology at the University of Toronto. He became the head of the physiology lab and an assistant to the dean of the medical school. He researched many topics, including how certain bacteria work, electroshocks, and blood flow in the brain. From 1905 onwards, he focused more on carbohydrate metabolism and diabetes. He published many scientific papers and books on these subjects. Macleod was also a popular teacher and helped create the six-year medical course at the University of Toronto.

The Discovery of Insulin

In late 1920, a young Canadian doctor named Frederick Banting approached Macleod. Banting had an idea to treat diabetes using an extract from the pancreas. Macleod was not very excited about this idea. He knew that other scientists had tried similar experiments without success. He also thought that the nervous system was more important in controlling blood sugar levels.

Even though Banting didn't have much experience in physiology, he convinced Macleod to let him use laboratory space. This happened during Macleod's summer vacation in Scotland. Macleod also provided animals for experiments and his student, Charles Best, to help. Macleod gave advice on how to plan the project and use scientific methods. He even helped with the first surgery on a dog.

While Macleod was away, Banting and Best made a big discovery. They isolated a substance from the pancreas. They successfully used it to lower the blood sugar of another dog whose pancreas had been removed.

When Macleod returned, he was surprised and had some doubts about their results. Banting felt that Macleod was questioning his honesty. They had a strong disagreement. However, Banting eventually agreed that more experiments were needed. He also convinced Macleod to provide better working conditions and pay for him and Best.

Further experiments were successful. The three scientists began to present their work at meetings. Macleod was a much better speaker than Banting. Banting started to believe that Macleod wanted to take all the credit. For example, at a presentation in December 1921 at Yale University, Banting became very nervous. Macleod stepped in and finished the presentation. Banting felt that Macleod was trying to steal his credit.

Their discovery was first published in February 1922. Macleod did not want to be listed as a co-author at first. He thought it was Banting's and Best's work. Even with their success, they needed to find a way to get enough pancreas extract for more experiments. The three researchers worked together and developed a better way to extract the substance using alcohol. This method was much more effective. This convinced Macleod to focus the entire lab on insulin research. He also brought in a biochemist named James Collip to help purify the extract.

The first test on a human was not successful. Banting felt left out because he wasn't qualified to participate. By the winter of 1922, he thought that all of Macleod's colleagues were working against him. There was even a reported fight between Banting and Collip. Banting saw Collip's breakthrough in purifying the extract as a threat. Collip didn't want to share the details. Collip even threatened to leave because of the tension. But others encouraged him to stay, seeing the great potential of their research.

In January 1922, the team performed the first successful human trial. It was on a 13-year-old boy named Leonard Thompson. Many more successful trials followed.

Even though all team members were listed as authors on their papers, Banting still felt ignored. This was because Macleod took over coordinating the human trials and getting larger amounts of the extract. Macleod's presentation in Washington, D.C., in May 1922 received a standing ovation. But Banting and Best refused to attend as a protest.

At that time, demonstrations of how well the method worked attracted huge public interest. The effect on patients, especially children who were expected to die, seemed almost like a miracle. The drug company Eli Lilly and Company started making insulin in large amounts. The patent (the right to make and sell it) was given to the British Medical Research Council. This was done to prevent anyone from unfairly profiting from the discovery.

In the summer of 1923, Macleod went back to other research. He studied fish that have separate parts for islet and acinar tissue in their pancreas. Working at the Marine Biological Station, he made extracts from these parts separately. He proved that insulin comes from the islet tissue, not the acinar tissue.

Meanwhile, Banting stayed in Toronto. Their relationship got worse again because of different stories in the news. Banting eventually started saying that he deserved all the credit. He claimed that Macleod had only held him back and had done nothing helpful except leave the lab keys when he went on vacation. Macleod wrote a report in 1922 to explain his side of the story. But he mostly avoided getting involved in the arguments about who deserved credit. Banting strongly disliked him, and they never spoke again. When Macleod left the University of Toronto in 1928, Banting refused to attend his farewell dinner.

Later Years and Legacy

Macleod returned to Scotland in 1928. He became a professor at the University of Aberdeen, taking over from his former teacher, John Alexander MacWilliam. He later became the Dean of the University of Aberdeen Medical Faculty. From 1929 to 1933, he was also a member of the Medical Research Council.

Macleod did not continue to work on insulin. However, he remained active as a researcher, lecturer, and author. His last major contribution was proving that the central nervous system plays an important role in keeping carbohydrate metabolism balanced. This was his original idea. His theory that fats could turn into carbohydrates was never fully proven, even though he found some indirect evidence.

In his free time, he enjoyed golf, motorcycling, and painting. He was married to Mary W. McWalter, but they did not have children. He died in 1935 in Aberdeen after several years of suffering from arthritis. Despite his illness, he remained active almost until his death. In 1933, he gave lectures in the US. In 1934, he published the 7th edition of his book Physiology and Biochemistry in Modern Medicine.

After Banting died in a plane crash in 1941, Best and his friends continued to spread Banting's version of the discovery. They tried to remove Macleod and Collip from the history books. It wasn't until 1950 that the first independent review of the story was made. This review gave credit to all four members of the team. However, Macleod's public image remained poor for many years after that. For example, a 1973 British TV show showed him in a negative way. The second TV show about the discovery, Glory Enough for All (1988), finally showed him more fairly. By then, it was widely accepted that Banting's and Best's story was not entirely accurate. More documents became public, allowing for a clearer understanding of what happened. Until Best died, these documents had been kept secret for over 50 years by the University of Toronto. The university wanted to avoid making the controversy worse.

Works

Macleod wrote a lot of scientific material. His first academic paper was about phosphorus in muscles, published in 1899. During his career, he wrote or helped write over 200 papers and eleven books. Some of his books include:

- Practical Physiology (1903)

- Recent Advances in Physiology (with Leonard E. Hill, 1905)

- Diabetes: its Pathological Physiology (1913)

- Physiology for dental students (with R. G. Pearce, 1915)

- Physiology and Biochemistry in Modern Medicine (1st edition 1918)

- Insulin and its Use in Diabetes (with W. R. Campbell, 1925)

- Carbohydrate Metabolism and Insulin (1926)

- The Fuel of life: Experimental Studies in Normal and Diabetic Animals (1928)

Awards and Honours

John Macleod was a respected physiologist even before insulin was discovered. He became a member of the Royal Society of Canada in 1919. In 1921, he became president of the American Physiological Society. In 1923, Macleod received the Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh. After 1923, he received many other honors. These included memberships in the Royal Society and the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He also became a member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina and an honorary member of the Regia Accademia Medica.

Macleod's reputation in Canada was affected by Banting and Best's story for many decades. He was not as highly regarded there. It was only in the 1980s that people generally accepted that Banting's and Best's story was not completely true. More documents became public, which helped to understand exactly what happened. Until Best died, these documents were kept secret for over 50 years by the University of Toronto. The university wanted to avoid making the controversy worse. Today, Macleod's scientific contributions are recognized by many people, even in Canada. The auditorium of the Toronto University Medical Research Center is named after him. Also, Diabetes UK has an award named after him for patients who live with diabetes for 70 years. In 2012, he was added to the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame.

Nobel Prize Recognition

The Nobel Committee quickly reacted to the first successful human trials of insulin. In the autumn of 1923, Banting and Macleod received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. This happened even though the long-term importance of the discovery was not yet fully clear. They were nominated by August Krogh, a Danish physiologist and Nobel winner whose wife had diabetes. Krogh had visited Macleod's lab and brought the insulin method back to Denmark.

Banting had friends in Toronto who wanted him to be honored as the discoverer of insulin. However, many experienced scientists believed that Banting and Best's early research would not have succeeded without the help of both Macleod and Collip. The Nobel Committee decided that Macleod's work was very important. This included his help in understanding the data, managing the human trials, and presenting the work clearly to the public. They concluded that Banting would not have found insulin without Macleod's guidance. So, they awarded the Nobel Prize to both of them.

Banting was very angry because he believed Best should have received the other half of the prize. He even thought about refusing the award. But he was convinced to accept it and then gave half of his prize money to Best. Macleod, in turn, gave half of his prize money to Collip. In 1972, the Nobel Foundation officially admitted that not including Best was a mistake.

Another debated point about the award was that eight months before Banting and Best's paper, a Romanian physiologist named Nicolae Paulescu had reported discovering a pancreas extract. He called it pancrein, and it also lowered blood sugar. Banting and Best even mentioned him in their paper. But they misunderstood his findings, possibly because of a translation error from French. Best publicly apologized for that mistake many years later.

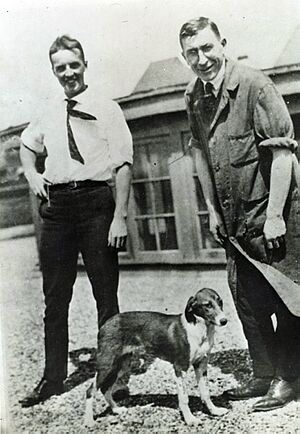

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: John James Rickard Macleod para niños

In Spanish: John James Rickard Macleod para niños

- List of Case Western people

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |