History of schools in Scotland facts for kids

The history of schools in Scotland tells us how education has changed over time, from the early Middle Ages to today. Long ago, there were schools for bards, who were poets and musicians. Monasteries were also important places for learning. Later, new types of schools appeared, like choir schools and grammar schools. These often trained young boys to become priests.

By the end of the Middle Ages, grammar schools were common in towns. Smaller "reading schools" taught basic skills in the countryside. Wealthy families sometimes had "household schools" for their children. Girls from noble families learned in nunneries. By the late 1400s, Edinburgh even had "sewing schools" for girls. Before the Reformation, there were about 100 different schools. A new law, the Education Act 1496, made education even more important.

After the Protestant Reformation in 1560, there was a big plan for a school in every parish (local area). However, this was too expensive. Existing schools in towns continued, becoming grammar schools or parish schools. Many private "adventure schools" also popped up. Girls were often only allowed in parish schools if there weren't enough boys. They were usually taught separately and for less time.

Laws in 1616, 1633, 1646, and 1696 made landowners build schools and pay teachers, called "dominies". Local church groups oversaw the teaching. By the late 1600s, most Lowland areas had parish schools. However, the Scottish Highlands still lacked basic education.

In the 1700s, new wealth helped rebuild many schools. Poor girls often went to "dame schools" run by women. Literacy was lower in the Highlands. By the 1800s, churches opened many "assembly schools" and "sessional schools" for poor children. The Disruption of 1843 split the church, creating new Free Church schools. Catholic schools also started for Irish immigrants. Sunday schools and "ragged schools" helped provide education for many children.

The Education (Scotland) Act 1872 created School Boards across Scotland. These boards took over church schools and made school attendance compulsory. The 1918 Act made secondary education free for everyone. More students stayed in school, and the leaving age was raised to 16 in 1973. Secondary education grew a lot, especially for girls. New qualifications were created, and by the 1980s, girls' achievements matched boys'.

Contents

Schools in the Middle Ages

Early Learning Centers

In the early Middle Ages, Scotland had bardic schools. These schools trained people in poetry and music. But because most people didn't read or write, we don't have much information about what they taught. When Christianity came to Scotland in the 500s, Latin became important. Monasteries became centers of learning. They often ran schools and taught a small group of educated men. These men were vital for creating and reading documents in a society where most people couldn't read.

New Schools Emerge

In the High Middle Ages, new types of schools appeared. Choir schools taught music, and grammar schools focused on Latin. These schools trained priests. When the church was reorganized around 1100, towns like Perth got schools. These schools were usually linked to monasteries. Early grammar schools include the High School of Glasgow (1124) and the High School of Dundee (1239). They were often part of cathedrals or large churches.

New religious groups also brought more education. Benedictine and Augustinian monasteries likely had "almonry schools." These were charity schools that helped poor boys get an education. Some monasteries, like Kinloss Abbey, also taught the sons of wealthy families. St Andrews had both a grammar school and a song school.

Education Grows in the Late Middle Ages

The number of song and grammar schools grew quickly from the late 1300s. Many new churches needed trained singers. Sometimes, students learned both music and grammar. Dominican friars were known for their teaching. They often taught grammar in towns like Glasgow. By the end of the Middle Ages, grammar schools were in all major towns.

In rural areas, education was less common. But there were "petty" or "reading schools" for basic learning. Wealthy families also hired private tutors. Sometimes, these tutors taught other children from the neighborhood, creating "household schools." Most of these schools were for boys. Girls from noble families went to nunneries to learn. By the late 1400s, Edinburgh had "sewing schools" for girls. These schools probably taught reading too.

Before the Reformation, there's proof of about 100 different schools. Most teachers were clergy members. The church controlled education, but lay people (non-clergy) became more interested. This sometimes caused arguments, like when Aberdeen hired a non-clergy teacher in 1538. Education began to expand beyond training for the church. The Education Act 1496 was a big step. It said that sons of barons and wealthy landowners should go to grammar school to learn "perfect Latin." This led to more people being able to read, especially wealthy men.

Early Modern Era Schools

The Reformation's Impact

Protestant reformers believed education was important for a moral society. After Protestants gained power in 1560, the First Book of Discipline suggested a school in every parish. But this was too expensive to do everywhere. In towns, existing schools continued. Song schools became reformed grammar schools or regular parish schools. Schools got money from the church, local landowners, and parents who could pay. Local church groups checked the teaching quality.

Many private "adventure schools" also existed. Parents often set these up with unlicensed teachers. The church sometimes tried to stop them, but they were often needed in large parishes. These private schools were important for girls and poor children. Teachers in parish schools often had other jobs to make enough money. By the 1600s, more university graduates became teachers. There's evidence of about 800 schools between 1560 and 1633. Parish schools taught in English and were for younger children. Grammar schools taught boys Latin until about age 12. Good grammar schools taught Latin, French, literature, and sports.

People generally thought women had limited abilities. But after the Reformation, women were expected to be more responsible, especially as wives and mothers. This meant they needed to read the Bible. However, most people didn't think girls should get the same academic education as boys. Girls were only allowed in parish schools if there weren't enough boys to pay the teacher. Girls from poorer families benefited from more parish schools. But they were usually outnumbered by boys. They were often taught separately, for less time, and to a lower level. Girls often learned reading, sewing, and knitting, but not writing. Many noblewomen, like Mary, Queen of Scots, were well-educated.

Schools in the 1600s

In 1616, a law said every parish should have a school if possible. Later, in 1633, a tax on landowners was introduced to fund schools. From 1638, Scotland had a "second Reformation." Education remained very important to the Covenanters, who supported the church's principles. A loophole in the education tax was closed in 1646. This law strengthened schools, with church groups overseeing them.

Even though the monarchy returned in 1660, a new law in 1696 brought back the 1646 rules. It made sure there was a school in every parish. In rural areas, landowners had to provide a schoolhouse and pay a teacher, called a "dominie." Local church groups checked the education quality. In towns, local councils ran burgh schools. Some wealthy people built "hospitals," which were boarding schools for deserving students. George Heriot's School in Edinburgh, founded in 1628, is an example. By the late 1600s, most Lowland areas had a complete network of parish schools. But many parts of the Scottish Highlands still lacked basic education.

Schools in the 1700s

New School Buildings

Wealthy people continued to build "hospitals" like Robert Gordon's Hospital in Aberdeen. Until the late 1700s, most school buildings looked like regular houses. But new wealth from farming improvements led to many schools being rebuilt. Most schools had one large room for up to 80 students, taught by one teacher. There might be smaller rooms for young children or girls. A teacher's house was often nearby.

By the late 1700s, many town schools changed. They started teaching new subjects like business. From the 1790s, city schools were often rebuilt in a grander style. They were funded by public donations and renamed "academies."

The "Democratic Myth"

Scotland's many parish schools led to a belief called the "democratic myth." This was the idea that any clever boy could rise through the school system to achieve great things. It also suggested that more people could read in Scotland than in England. However, historians now know that very few boys actually became successful this way. Also, literacy rates in Scotland were not much higher than in other countries. Parish school education was basic and short, and attendance was not required.

Girls' Education

By the 1700s, many poorer girls learned in "dame schools." These were informal schools run by women who taught reading, sewing, and cooking. Girls from wealthy families learned basic reading, writing, needlework, and household skills. They also learned polite manners and religious lessons.

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, about 90% of female servants couldn't sign their names. By 1750, about 85% of women overall couldn't read or write. This was much higher than for men (35%). While Scotland's overall literacy was slightly higher than England's, Scottish girls' literacy was lower than English girls'.

Highland Challenges

In the Scottish Highlands, teaching was difficult. This was due to long distances, isolation, and teachers not knowing Scottish Gaelic. Gaelic was the main language there. The church's parish schools were helped by the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge (SSPCK) from 1709. The SSPCK wanted to teach English and reduce the influence of Catholicism. Although SSPCK schools eventually taught in Gaelic, their overall effect contributed to the decline of Highland culture. Literacy rates were lower in the Highlands. Despite efforts, many people still couldn't read or write in the 1800s.

Schools in the 1800s

Church Schools Grow and Divide

As cities grew and the population increased, there weren't enough schools. The Church of Scotland formed an education committee in 1824. By 1865, they had opened 214 "assembly schools." There were also 120 "sessional schools," mainly in towns, for poor children. The Disruption of 1843 split the church, creating the Free Church. This divided the church school system.

Many teachers joined the Free Church. By 1847, the Free Church claimed to have built 500 schools. They also had two teacher training colleges. Over 44,000 children were taught in Free Church schools. Many Irish immigrants arrived in the 1800s. This led to Catholic schools being set up, especially in Glasgow from 1817. By 1872, there were 65 Catholic schools with 12,000 students. The school system was now split among three main groups: the established Church, the Free Church, and the Catholic Church.

Extra Learning Opportunities

To help the parish system, Sunday schools were created. They started in the 1780s and were adopted by all religious groups in the 1800s. By the 1890s, they were very popular. In 1890, Baptists had more Sunday schools than churches. By 1895, 60% of children aged 5–15 in Glasgow were enrolled in Church of Scotland Sunday schools.

From the 1830s, there were also mission schools, ragged schools, and improvement classes. These were for all Protestants and aimed at working-class people in cities. The ragged school movement tried to give free education to very poor children. Thomas Guthrie, a Scottish minister, strongly supported ragged schools.

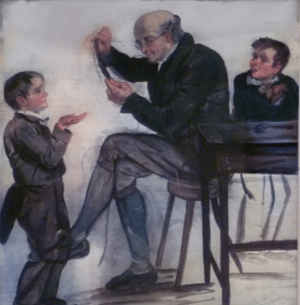

Teaching Ideas and Methods

Scots played a big part in training teachers. Andrew Bell developed the "Monitorial System." In this system, older students taught younger ones. This led to the "pupil-teacher" system. John Wood further developed this, favoring competition and strict rules.

In contrast, David Stow founded Scotland's first infant school in Glasgow in 1828. He believed play was important and influenced the idea of school playgrounds. He focused on the bond between teacher and child. He promoted the "Glasgow method," which used trained adult teachers. He started the first teacher training college in the UK. Scottish teachers were known for being strict and often using the tawse. This was a leather belt used for punishment on students' hands.

Government Reviews and Changes

Problems and divisions in the Scottish school system led to more government control. From 1830, the government started funding school buildings. In 1861, a law removed the rule that Scottish teachers had to be Church of Scotland members. In 1866, the government set up the Argyll Commission to study the school system.

The commission found that out of 500,000 children needing education, 200,000 were in good schools. Another 200,000 were in schools of uncertain quality. And 90,000 children received no education at all. This was better than England, but the report still pushed for big reforms. This led to the Education (Scotland) Act 1872.

The 1872 Education Act

The 1872 Act created about 1,000 regional School Boards. These boards immediately took over the schools run by the churches. They could also make sure children attended school. All children aged 5 to 13 had to go to school. Poverty was not an excuse, and some help was given to poor families. The boards built many large, purpose-built schools. The Scottish Education Department in London oversaw everything.

Schools were often very crowded after the act, with up to 70 children in one room. The focus on passing exams led to a lot of "learning by rote" (memorizing facts). Even the weakest children were drilled with facts. Many new schools were built between 1872 and 1914. Some were two stories tall, but in crowded cities, they could be four stories and hold 1,000 children. Episcopalian and Catholic schools remained outside this system. The number of Catholic schools grew to 188 by 1900.

Secondary Education Develops

The Scottish Act also included some plans for secondary education. The Scottish Education Department wanted to expand it, but not for everyone. They preferred to add vocational (job-related) teaching to elementary schools. These were called "advanced divisions" for students up to age 14. This was debated because it seemed to go against the idea that smart students could go to university.

Larger city school boards created about 200 "higher grade" (secondary) schools. These were cheaper than the old burgh schools. Some old grammar schools, like the High School of Glasgow, became senior secondary schools. Some "hospitals" became day schools. A few, like Fettes College, became private "public schools" like those in England. Other public schools also appeared around the mid-1800s.

Some worried that secondary education became harder for poor children to access. However, in the second half of the century, about a quarter of university students came from working-class backgrounds. In 1888, the Scottish Education Department introduced the Scottish Leaving Certificate exam. This set national standards for secondary education. In 1890, school fees were removed. This created a state-funded, free, and compulsory basic education system with common exams.

Schools in the 1900s

Early 1900s Changes

The Education (Scotland) Act 1918 made secondary education free for everyone. It took almost 20 years to fully put this into practice. Most advanced divisions in primary schools became "junior secondaries." Here, students got job-focused education until age 14. The old academies and Higher Grade schools became "senior secondaries." These offered a more academic education. They prepared students for the Leaving Certificate, which was needed to get into university.

Students were chosen for junior or senior secondaries at age 12. This was done with an intelligence test called the "qualy." The 1918 Act also brought Episcopalian and Roman Catholic schools into the state system. Catholic schools kept their religious character. This caused some protests from Protestants. The Act also replaced School Boards with 38 local education authorities. These were later taken over by local government in 1929. Between the two World Wars, new schools were built mostly in new housing areas.

Unlike England's 1944 Act, Scotland's 1945 Act mainly combined existing laws. This was because universal secondary education was already in place. Plans to raise the school leaving age to 15 in the 1940s didn't happen. But more students stayed in school beyond elementary education. The leaving age was finally raised to 16 in 1973. Secondary education grew a lot, especially for girls. They stayed in full-time education in increasing numbers. A 1947 report suggested ending selection for secondary schools. This idea became a goal for future reforms.

Late 1900s Developments

The Labour government ended selection for secondary schools in 1965. They suggested that councils create one type of comprehensive secondary school. These schools would take all children from a certain neighborhood. By the late 1970s, 75% of children were in non-selective schools. By the early 1980s, only 5% of children in private schools were chosen by selection.

New schools were built for new towns and housing areas. There wasn't a unique Scottish school building style. Designs were more open and less rigid, similar to England. Existing schools also changed to focus more on child-centered learning.

New qualifications were created to match changing goals and the economy. The Leaving Certificate was replaced by the Scottish Certificate of Education Ordinary Grade ('O-Grade') and Higher Grade ('Higher') in 1962. These became the main qualifications for university entry. In the 1980s, these were replaced by Standard Grade qualifications. More academic qualifications encouraged students to stay in school. In 1967, 22% of students stayed past age 15. By 1994, 74% stayed past age 16.

Local government was reorganized in 1975. Education was transferred to new authorities. This allowed them to share resources with poorer areas. Education became part of a wider social reform plan. In the 1980s, the school curriculum was updated. It aimed to help students of all abilities. Girls' achievements caught up with boys' in the early 1980s, and gender differences disappeared.

See also

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |