Housing discrimination in the United States facts for kids

Housing discrimination in the United States means that some people face unfair treatment when they try to find a home. This can be when they want to buy, rent, or even live in a certain neighborhood. This problem became much bigger after slavery ended in 1865. It was often part of Jim Crow laws, which forced people of different races to live separately.

The government started to fight these laws in 1917. The Supreme Court said that laws stopping Black people from living in white neighborhoods were against the rules. This was in a case called Buchanan v. Warley. But, even after this, the government itself sometimes caused housing discrimination. This happened through practices like redlining and special agreements called race-restricted covenants. These unfair practices continued until the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

This important law included the Fair Housing Act. It made it illegal for landlords or sellers to treat people differently because of their race, color, religion, gender, or where they came from. Later, these protections were also given to people with disabilities and families with children. Even with these laws, studies show that housing discrimination still happens. This unfairness has led to big differences in how much money people have, their education, and their health. It's a key example of systemic racism, which means unfairness built into systems and rules.

Contents

History of Housing Discrimination

After the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, Jim Crow laws were created. These laws led to unfair treatment of racial and ethnic minorities, especially Black Americans. While Jim Crow laws were common in the South, similar unfair practices appeared in the North.

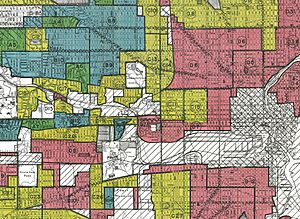

Between 1900 and 1920, many Black Americans moved to the North during the Great Migration. This led to strong reactions from white people in Northern cities. They started to use housing discrimination to keep neighborhoods separated. Tools like zoning (rules about how land can be used) and race-restricted covenants (agreements not to sell to certain groups) were used. In 1926, the Supreme Court even supported these covenants in the case of Corrigan v. Buckley. After this, these agreements became very popular across the country. They helped create neighborhoods that were only for white people.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) played a big part in housing discrimination. They had rules that openly discriminated against Black Americans. The FHA thought that if Black Americans lived in white neighborhoods, property values would go down. But this was proven wrong, as Black Americans were often willing to pay more to live in those areas.

The FHA also refused to give mortgage insurance for homes in Black neighborhoods. This practice was called redlining. It meant they rated neighborhoods based on how risky they were for loans. This risk level often depended on the race of the people living there. The FHA's rules even said they encouraged "prohibition of the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they were intended." This led developers to create rules to keep neighborhoods white.

The G.I. Bill helped many veterans buy homes after World War II. But this bill did not help Black veterans in the same way. This was because private lenders, not the government, gave out the loans. These lenders often used redlining to discriminate. For example, Levittown was a neighborhood built for returning veterans. But the developer would not let people of color live there. The FHA supported this by approving loans and allowing these race-restricted rules.

It wasn't until the Fair Housing Act in 1968 that the government took strong steps. This act made all types of housing discrimination illegal. It specifically banned practices like hiding information about homes, racial steering (guiding people to certain neighborhoods based on race), blockbusting (scaring white homeowners into selling cheaply), and redlining.

The Fair Housing Act

The Fair Housing Act was passed because President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed for it. Congress passed this law just one week after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr..

The Fair Housing Act made it illegal to:

- Refuse to sell or rent a home to someone because of their race, color, religion, sex, or where they came from.

- Treat people differently in the rules or costs of selling or renting a home based on these reasons.

- Advertise a home in a way that shows a preference or discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin.

- Threaten or stop someone from using their housing rights because of discrimination.

When the Fair Housing Act first started, it only banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. In 1988, it was updated to also include disability and "familial status." Familial status means if there are children under 18 in the household.

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is the government department that makes sure the Fair Housing Act is followed. They have an office called the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity (FHEO). This office helps people who think they have faced housing discrimination. You can file a complaint with FHEO for free. FHEO also works with local agencies that have similar fair housing laws.

There are also private, non-profit groups that help fight housing discrimination. Some get money from HUD, and others get donations. People who experience discrimination don't have to go through HUD. They can also take their case to federal courts. The United States Department of Justice can also file cases if there's a pattern of discrimination.

Enforcing the Law

The Fair Housing Act gave HUD the power to enforce the law. But at first, the ways to enforce it were not very strong. The Act has been made stronger since 1968, but enforcing it is still a challenge. For example, it's hard to make sure the law is followed everywhere.

Later Changes and Challenges

In 1968, a report called the Kerner Commission report suggested investing in housing to reduce segregation. The government passed other laws too. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 and the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 helped with discrimination in getting home loans.

The Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988 gave the government more power to enforce the original Act. It set up a system where special judges could hear cases and give out fines. Even with these efforts, many cases of discrimination still go unreported.

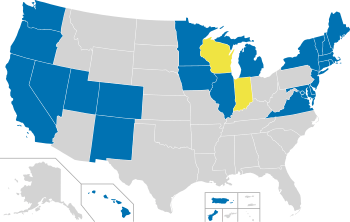

Some states have passed their own laws to stop housing discrimination. These laws sometimes ban landlords from refusing tenants who use Section 8 vouchers. These vouchers help low-income families afford housing. But studies show that many landlords still refuse to accept them.

The United States Census has shown that more ethnic and racial minorities lived in poor, concentrated areas after the Fair Housing Act was passed. This happened from 1970 to 1990. This doesn't always mean discrimination, but it shows a trend called "white flight." This was when many white families moved from cities to the suburbs in the 1970s and 80s. This left many cities with fewer white residents.

After the Fair Housing Act and the end of redlining, a new problem called "predatory inclusion" started. Government officials encouraged low-income Black Americans to buy homes. But the loans they received often had much worse terms than those for white families. Also, the houses were often in poor condition. Mortgage banks made money when these loans failed, hurting Black homeowners.

Current Housing Discrimination Practices

There are two main types of housing discrimination:

- Exclusionary discrimination: This is when someone is stopped from getting housing they want to rent or buy.

- Non-exclusionary discrimination: This is unfair treatment that happens while someone is already living in their home.

Some policies that don't seem to discriminate on the surface can still cause housing discrimination. This is called disparate impact. It means a rule or policy that seems fair actually hurts minorities or other protected groups more. For example, a rule that bans anyone with a criminal record might unfairly affect certain groups because of differences in the justice system.

Studies using "audit studies" have found strong proof of racial housing discrimination. In these studies, two people who are similar in every way except race try to rent or buy a home. A 2000 study by HUD found that white applicants were still favored over Black or Hispanic applicants about 25% of the time. Black and Hispanic applicants were often given less information or shown fewer, lower-quality homes.

LGBT Housing Discrimination

While housing discrimination often focuses on race, studies show a growing problem for people who are gay, lesbian, or transgender. The original Fair Housing Act did not specifically mention this type of discrimination. By 2007, only 17 states had laws against it.

In 2012, HUD announced new rules. These rules require all housing providers who get money from HUD to prevent discrimination based on gender identity.

Ethnic and Racial Minority Housing Discrimination

Ethnic and racial minorities are most affected by housing discrimination. Black Americans often face exclusionary discrimination when trying to rent or buy. Black women, especially single mothers, are often victims because of unfair stereotypes.

Non-exclusionary discrimination, like racial slurs or intimidation, also affects many minority victims. Sometimes, landlords might fix a white tenant's problem quickly but delay fixing a minority tenant's problem. Studies show that Black Americans file most housing discrimination cases. Hispanic and Asian American people also face unfair treatment when looking for homes.

Disability Housing Discrimination

The Fair Housing Act also bans discrimination based on disability. This means landlords cannot refuse someone because they have a disability. Also, a resident with a disability has the right to "reasonable accommodations." This means small changes to rules or property that help them use their home. A person with a disability is defined as someone with a physical or mental problem that greatly limits their daily activities.

Research shows discrimination against people who use wheelchairs or are deaf. Many landlords may not know their duties to provide accessible housing. A 2010 HUD study found discrimination against people with mental disabilities.

Gender Discrimination

Studies have also found unfair treatment based on gender in the rental housing market. For example, a study found that applicants with minority and male-sounding names were treated unfairly even when they had the same qualifications.

Effects of Housing Discrimination

Housing discrimination has many serious effects. One of the clearest is concentrated poverty. This means many poor people live together in one area. People who face housing discrimination often end up in lower-quality homes. This is linked to how money is spread unevenly in society.

Poor areas often have worse schools. A poor education can lead to lower earnings. People who earn less can only afford lower-quality housing. This creates a cycle. Segregation, health risks, and differences in wealth are all connected to poverty.

Residential Segregation

The most obvious result of housing discrimination is residential segregation. This means people of different races or groups live separately. Housing discrimination makes this worse through unfair home loans, redlining, and unfair lending practices. Threats and avoidance also lead to segregation.

After the Brown v. Board of Education court case, many white families moved out of cities to avoid integrated schools. This was called White flight. This was made easier by FHA rules like race-restricted deeds. This led to "urban decay," where city areas became run down. It also made the difference between city and suburban schools much wider.

In 1990, about 57% of Black Americans and 51% of Hispanic Americans lived in inner cities. Only about 25% of white Americans did. By 2002, the average white person lived in a neighborhood that was 80% white. The average Black American lived in a neighborhood that was 51% Black. These numbers show how segregated communities still are.

Neighborhood and Educational Effects

Housing discrimination also affects neighborhoods and schools. Living in lower-quality housing means fewer good things in the neighborhood, like parks or stores. Education is closely linked to housing. For schools to be integrated, neighborhoods need to be integrated.

Educational differences exist between rich and poor areas. Poorer areas often have worse schools. This leads to fewer job opportunities and higher dropout rates. Schools are often segregated because of housing discrimination. This hurts students' learning. Schools with many disadvantaged students often have worse results. This is known as the achievement gap. Studies have shown that low-income students do better when they attend schools in wealthier areas.

Wealth Disparities

There are big differences in how much money white and Black households have. White households have much more wealth. Experts say that these wealth differences are a result of housing discrimination. This is because it stops people from buying homes. Homeownership is a key way to build wealth.

Black homeowners and renters were often exploited. They paid higher prices for homes and apartments than people in white neighborhoods. This "race tax" made it harder for them to save money and build wealth.

Homeowners can learn important skills like managing money and home repairs. Children of homeowners are also less likely to drop out of high school. Housing discrimination stops families from getting affordable loans and living in areas where property values go up. This keeps them from building wealth. Segregation also leads to wealth differences that pass down through families. If parents were forced into poor housing, they have less wealth to pass on to their children.

Possible Solutions

Experts say that housing discrimination is always changing. As old unfair rules are stopped, new ways of discriminating appear.

One suggested solution is to do more "paired testing" research. This means sending two similar people, but of different races, to a landlord or real estate agent. Then, researchers compare how they are treated. These tests have shown that real estate agents often show white families more homes than Black or Latino families.

Enforcing fair housing laws has been a challenge. The main responsibility falls on government agencies like the Federal Reserve Board and HUD. The enforcement parts of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 were weak at first. Even with changes in 1988, it's still hard to catch discrimination because it often happens in private. The 1988 amendment did create a system of judges to hear these cases.

Other ideas include making sure neighborhoods are truly integrated. This is called "inclusionary housing." It helps racial minorities find and keep jobs. For example, one county in Maryland passed a law that requires new housing developments to include some affordable homes.

Another solution is to use subsidies. These are payments or help from the government. They can be direct payments, help for specific housing projects, or help for families. Only a small number of poor households receive federal housing help. One experiment called Moving to Opportunity gave vouchers to families that could only be used in low-poverty neighborhoods. This helped improve their health and mental well-being.

Experts also say it's important to focus on city planning and policies. They suggest "Equitable Development." This approach aims to create communities where everyone has a fair chance. It means working together—government, private businesses, and community groups—to make policies that promote fairness, economic growth, and a healthy environment.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |