Jacob Theodor Klein facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacob Theodor Klein

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Jacob Theodor Klein

15 August 1685 |

| Died | 27 February 1759 (aged 73) |

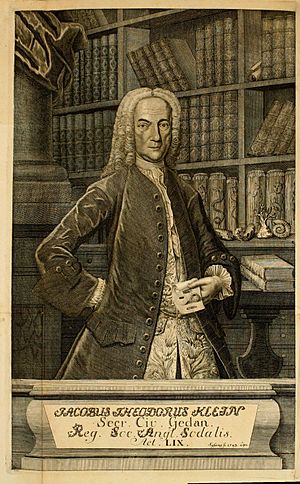

Jacob Theodor Klein (born August 15, 1685 – died February 27, 1759) was a very smart German man. He worked as a jurist (a legal expert) and a diplomat (someone who represents their country). He was also a historian, botanist (plant expert), zoologist (animal expert), and mathematician. He even worked for the Polish King August II the Strong.

Contents

Life of Jacob Theodor Klein

Jacob Theodor Klein was born in Königsberg, which is now Kaliningrad, Russia, on August 15, 1685. He went to the University of Königsberg to study nature and history.

From 1706 to 1712, Klein traveled a lot. He visited England, Germany, Holland, and Austria to learn more. After his travels, he went back to Königsberg.

When his father passed away, Klein moved to Danzig (now Gdańsk). In 1713, he was chosen to be the city's secretary. From 1714 to 1716, he worked as Danzig's special representative in Dresden and Warsaw.

Klein started his scientific work in 1713. By 1722, he began sharing his discoveries. He became a member of the Institute of Sciences in Bologna. He was inspired by Johann Philipp Breyne and focused on how to name and group animals. Klein even created his own system for classifying animals. This system looked at the number, shape, and position of their legs or fins.

Because of his important work in science, Klein became a member of many famous groups. These included the Royal Society in London and the Danzig Research Society.

One of Klein's daughters, Dorothea Juliane Klein, married a physicist named Daniel Gralath. Daniel later became the mayor of Danzig. He inherited Klein's large library, which was admired by the famous Swiss mathematician Johann Bernoulli.

Jacob Theodor Klein died in Danzig on February 27, 1759.

Klein's Botanical Garden and Museum

In 1718, Klein used his position as Danzig's secretary to create a botanical garden. He got help from other smart people. This garden became one of the biggest of its time.

The garden grew to include more than just plants. It had live animals, collections of animal specimens, fossils, and even amber. It also held a large collection of shells. Klein built a special greenhouse to experiment with plants from faraway places.

This amazing collection became known as the Museum Kleinianum. In 1740, Klein sold the museum to Margrave Friedrich of Brandenburg-Kulmbach. After the Margrave died in 1763, the collection was given to the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg. The famous mathematician Johann Bernoulli visited the museum and praised it.

Klein's Scientific Discoveries

Animal Classification System

Jacob Theodor Klein became very interested in science around 1713. He started publishing his findings in 1722. He especially liked to organize living things into groups, which is called classification. However, he did not include insects in his system.

Klein's system for classifying animals was based on things you could easily see. For example, he looked at the number, shape, and position of their limbs (like legs or fins). This was different from the system used by Carl von Linné, another famous scientist. Klein didn't agree with Linnaeus's ideas. Even though Linnaeus's system is more widely used today, some of Klein's classifications are still helpful. For instance, his work helped name some types of echinoderms (like sea urchins). His research on sea urchins was the best information available at the time.

In his essay Tentamen Herpetologiae (1755), Klein was the first to use the word "herpetology". This word means the study of amphibians and reptiles. However, his classification system grouped animals like frogs (amphibians) and lizards (reptiles) together. He believed that only features that were easy to recognize should be used to classify animals.

Understanding Fish Hearing

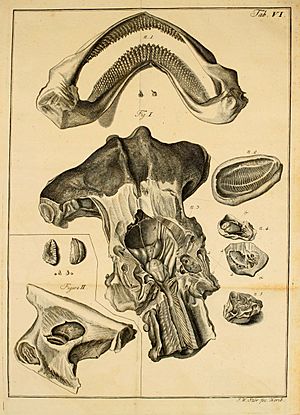

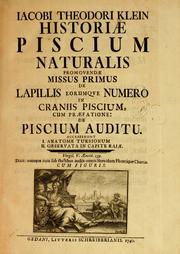

In 1744, Klein published an important book called Historiae Piscium Naturalis. This book was about how fish hear. He dedicated it to the Royal Society.

Before Klein's book, people thought that only certain types of fish had ear holes. It was not clear if fish could hear at all. The ancient Greek thinker Aristotle believed fish must hear, even though he couldn't find their ears.

In his book, Klein talked about tiny bones in the heads of fish. He called them "Ossicula," meaning "little bones." He believed these bones were the fish's hearing organs. He noticed that these bones grew bigger as the fish grew. He also thought you could tell a fish's age by looking at the rings on these bones. Today, we call these bones "otoliths," and we know they do get a growth ring every day for at least the first six months of a fish's life.

Klein also looked closely at the heads of fish, like pike and sturgeon. He found small holes and passages that led to these hearing bones. He concluded that fish do have hearing organs and passages. He explained that water actually helps sound travel to fish, rather than blocking it. He also noted that the hearing organs of different types of fish (like bony fish and cartilaginous fish) look different.

Honours and Recognition

Klein was honored with membership in several important scientific groups. These included the Royal Society in London and the St. Petersburg Academy.

The plant genus Kleinia was named after him by Linnaeus to celebrate Klein's work. Professor Johann Daniel Titius even called Klein the most important natural philosopher of his century.

Criticism of Klein's Ideas

Even though many people respected Klein, some thought his ideas were not always scientific. They said he sometimes based his beliefs on stories from people who might not have been accurate.

For example, in 1760, a scientist named Peter Collinson criticized Klein. Klein believed that swallows (a type of bird) did not fly south for winter. Instead, he thought they went underwater! Collinson said this idea was "against nature and reason." He used observations from sailors to show that swallows do migrate.

List of Klein's Works

- Natürliche Ordnung und vermehrte Historie der vierfüssigen Thiere. (Natural Order and Expanded History of Four-footed Animals) Schuster, Danzig 1760

- Verbesserte und vollständigere Historie der Vögel (Improved and More Complete History of Birds) Schmidt, Leipzig, Lübeck 1760

- Stemmata avium. (Families of Birds) Holle, Leipzig 1759

- Tentamen herpetologiae. (An Attempt at Herpetology) Luzac jun., Leiden, Göttingen 1755

- Doutes ou observations de M. Klein, sur la revûe des animaux, faite par le premier homme, sur quelques animaux des classes des quadrupedes & amphibies du systême de la nature, de M. Linnaeus. (Doubts or Observations by Mr. Klein, on the Review of Animals by the First Man, on Some Animals of the Quadruped and Amphibian Classes in Mr. Linnaeus's System of Nature) Bauche, Paris 1754

- Ordre naturel des oursins de mer et fossiles, avec des observations sur les piquans des oursins de mer, et quelques remarques sur les bélemnites ... (Natural Order of Sea Urchins and Fossils, with Observations on the Spines of Sea Urchins, and Some Remarks on Belemnites) Bauche, Paris 1754

- Tentamen methodi ostracologicæ sive Dispositio naturalis cochlidum et concharum in suas classes, genera et species. (An Attempt at an Ostracological Method or Natural Arrangement of Snails and Shells into Their Classes, Genera, and Species) Wishoff, Leiden 1753

- Quadrupedum dispositio brevisque historia naturalis. (Arrangement and Brief Natural History of Quadrupeds) Schmidt, Leipzig 1751

- Historiae avium prodromus. (Introduction to the History of Birds) Schmidt, Lübeck 1750

- Mantissa ichtyologica de sono et auditu piscium sive Disquisitio rationum, quibus autor epistolae in Bibliotheca Gallica de auditu piscium, omnes pisces mutos surdosque esse, contendit. (Ichthyological Supplement on the Sound and Hearing of Fish, or an Inquiry into the Reasons by Which the Author of the Letter in the Gallic Library Contends that All Fish are Mute and Deaf) Leipzig 1746

- Historiæ piscium naturlais promovendæ missus quartus de piscibus per branchias apertas spirantibus ad justum numerum et ordinem redigendis. (Fourth Treatise for Promoting the Natural History of Fish, on Fish Breathing Through Open Gills to be Reduced to the Correct Number and Order) Gleditsch & Schreiber, Leipzig, Danzig 1744

- Summa dubiorum circa classes quadrupedum et amphibiorum in celebris domini Caroli Linnaei systemate naturae. (Summary of Doubts Concerning the Classes of Quadrupeds and Amphibians in the System of Nature of the Celebrated Mr. Carl Linnaeus) Leipzig, Danzig 1743

- Naturalis dispositio echinodermatum. (Natural Arrangement of Echinoderms) Schreiber, Danzig 1734

- Descriptiones tubulorum marinorum. (Descriptions of Marine Tubes) Knoch, Danzig 1731

- An Tithymaloides. Schreiber, Danzig 1730

- Petri Artedi operum brevis recensio, 1738, British Library, Sloane MS 4020, ff. 194–197; Theodore W. Pietsch & Hans Aili, "Jacob Theodor Klein's critique of Peter Artedi's Ichthyologia (1738), Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift Årgång 2014, p. 39–84.

See also