Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Baron Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen

|

|

|---|---|

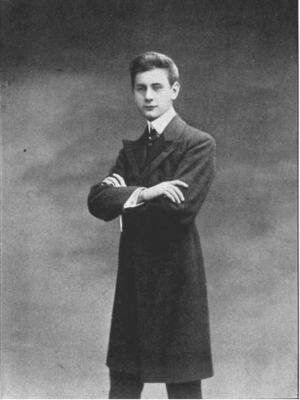

D'Adelswärd-Fersen in 1905

|

|

| Born | 20 February 1880 Paris, France

|

| Died | 5 November 1923 (aged 43) Capri, Italy

|

| Resting place | Cimitero acattolico ("Non-Roman-Catholic cemetery"), Capri |

| Occupation | Writer and poet |

| Known for | Lord Lyllian Akademos Being the subject of Roger Peyrefitte's novel L'Exilé de Capri |

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

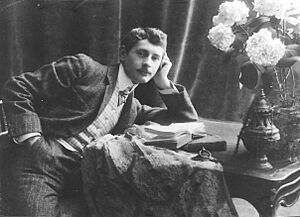

Baron Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen (born February 20, 1880 – died November 5, 1923) was a French novelist and poet. His life story inspired the 1959 novel The Exile of Capri by Roger Peyrefitte.

After 1903, he lived mostly on the island of Capri in Italy. He became a well-known person on the island. His beautiful house, Villa Lysis, is still a popular place for tourists to visit today.

Contents

Early Life and Writings

Jacques d'Adelswärd was born in Paris, France, on February 20, 1880. His father was Axel d'Adelswärd, and his mother was Louise-Emilie Alexandrine d'Adelswärd. His family had a long history, including a distant relative named Axel von Fersen Jr., a Swedish count. Jacques later added "Fersen" to his name to honor this connection.

His family was involved in the steel industry, which made them quite wealthy. When Jacques was 22, he inherited a large fortune. He studied at the Sciences Po in Paris and the University of Geneva. Instead of joining the military, he chose to travel widely and become a writer.

Jacques visited Capri and other parts of Italy with his mother in 1897. He published his first poems, Chansons légères, in 1900, and Hymnaire d'Adonis in 1902. He also wrote novels, including Notre Dame des mers mortes.

Life on Capri Island

Building Villa Lysis and Traveling the World

Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen decided to build a house on the island of Capri. He bought land on a hill, not far from where the Roman emperor Tiberius once had his own villa. He asked his friend Édouard Chimot to design the house. It was first called Gloriette, but later became Villa Lysis. The name Lysis comes from an ancient Greek book by Plato.

While his villa was being built, Jacques traveled to the Far East. He spent time in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where he wrote his novel Lord Lyllian. He returned to Capri in 1904, after visiting the United States.

At one point, he had to leave Capri for a short time. This was because some islanders blamed him for an accident that happened to a local worker during the villa's construction. He went to Rome, where he met a young man named Nino Cesarini, who became his secretary and companion. In 1905, Jacques and Nino visited Sicily.

The construction of Villa Lysis was finished in July 1905. The villa has a unique style, sometimes called "Neoclassical decadent." It features a large garden with steps leading to an Ionic portico. Inside, a beautiful marble staircase leads to bedrooms with amazing views.

Jacques and Nino traveled to Paris and then to Oxford. After returning to Capri, they went on another long journey to China with their four servants. They all came back to Villa Lysis in early 1907.

Leaving and Returning to Capri

In 1909, Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen published a novel about Capri called Et le feu s'éteignit sur la mer… (And the fire was smothered by the sea). Some people on the island recognized themselves in the book and were not happy. The local council of Capri tried to have him leave the island.

Authorities also used parties Jacques held to celebrate Nino Cesarini's army enlistment and 20th birthday as a reason to ask him to leave. Jacques chose to leave Italy voluntarily. He returned to France in November 1909, and Nino Cesarini went with him.

They did not stay in Paris for long. They moved to Porquerolles and later to Nice. Jacques also traveled to the Far East again, returning in 1911. After Nino finished his military service, they went on another trip through the Mediterranean to the Far East. They returned to Nice in 1912.

Jacques was allowed to return to Capri in April 1913. He wrote a poem called Ode à la Terre promise (Ode to the Promised Land) to celebrate his return to the island.

Later Years on Capri

When World War I began in 1914, French authorities asked Jacques to join the military. However, doctors found him unfit for service and declared him to be very ill. He spent the rest of his life mostly at Villa Lysis on Capri.

He passed away on Capri in 1923. His companion, Nino Cesarini, returned to Rome.

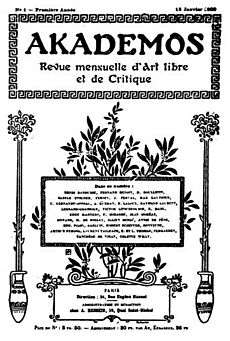

Akademos Magazine

In 1909, Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen tried publishing a monthly literary magazine called Akademos. Revue Mensuelle d'Art Libre et de Critique. It was a very fancy magazine, printed on different types of expensive paper. It featured articles and poems by famous writers like Colette and Maxim Gorky.

Jacques carefully included themes related to same-sex relationships in each issue, often through poems or articles. This made Akademos one of the first French magazines to openly discuss such topics. He had studied similar German magazines, like Der Eigene, before starting his own.

Akademos only lasted for one year, with twelve issues. It might have been too expensive to produce, or perhaps there wasn't enough public interest or support from other newspapers.

Media and Legacy

Films and Music Inspired by His Life

Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen's life has inspired some films and music:

- Capri – Musik die sich entfernt, oder: Die seltsame Reise des Cyrill K. (1983): This made-for-TV movie featured Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen and other famous people from Capri's past.

- A music video for soprano Nicole Renaud singing Jacques's poem, Mon cœur est un bouquet, was filmed at Villa Lysis on Capri.

- The French soprano Nicole Renaud also used four of Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen's poems for the lyrics of her song Les amants solitaires.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen para niños

In Spanish: Jacques d'Adelswärd-Fersen para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |