John B. Calhoun facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John B. Calhoun

|

|

|---|---|

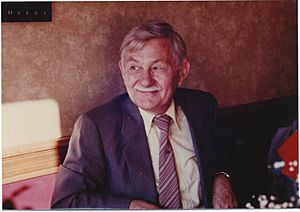

John Calhoun in the fall of 1986 at the baby shower of his first grandchild.

|

|

| Born | May 11, 1917 Elkton, Tennessee, U.S.

|

| Died | September 7, 1995 (aged 78) |

| Occupation | ethologist |

| Known for | Behavioral sink theory |

John Bumpass Calhoun (born May 11, 1917 – died September 7, 1995) was an American scientist who studied animal behavior. This field is called ethology. He was famous for his research on how living in very crowded spaces affects animals.

Calhoun believed that the bad effects of overpopulation on rodents could show what might happen to humans. He created the term "behavioral sink" to describe strange behaviors in crowded groups. He also called some quiet, withdrawn animals "beautiful ones." His work became well-known around the world.

Contents

Early life and education

John Bumpass Calhoun was born on May 11, 1917, in Elkton, Tennessee. He was the third child in his family. His father was a high school principal, and his mother was an artist.

His family moved several times, ending up in Nashville when John was in junior high. Around this time, he became very interested in birds. He joined the Tennessee Ornithological Society. A woman named Mrs. Laskey, who studied birds, greatly influenced him.

Calhoun spent his teenage years putting bands on birds and recording their habits. He even had his first article published in a science journal when he was just 15 years old!

University studies

John Calhoun went to the University of Virginia and earned his first degree in 1939. During his summer breaks, he worked at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., studying birds.

He then went on to get his master's and Ph.D. degrees from Northwestern University in 1942 and 1943. His main research for his Ph.D. was about the daily routines of the Norway rat. At Northwestern, he met Edith Gressley, who later became his wife.

Career and famous experiments

Early rat studies

After finishing his studies, Calhoun taught at different universities. In 1946, he started working on the Rodent Ecology Project at Johns Hopkins University.

In March 1947, he began a long study of a group of Norway rats. He put them in a large outdoor pen. Even though many rats could have been born, the population never grew beyond 200 rats. It usually stayed around 150. He noticed that the rats formed small groups of about twelve. He thought that twelve rats was the most that could live together peacefully. More than that caused stress.

He continued studying rats until 1951. During this time, his first daughter was born.

Norway rat experiments in a controlled environment

In 1954, Calhoun started working at the National Institutes of Health, where he stayed for 33 years. He continued his experiments with domesticated Norway rats in a special lab.

His lab was set up like a small city for rats. It had four rooms, each with different areas for sleeping, eating, and drinking. Ramps connected some of the rooms. This setup allowed him to watch how the rats behaved in different parts of their environment. He noticed that certain areas became very crowded, leading to unusual behaviors. This led to his idea of "behavioral sinks."

These experiments lasted from 1958 to 1962.

The mouse universe experiment

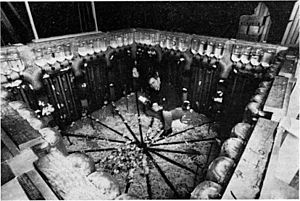

In the early 1960s, Calhoun started his most famous experiment, called the "mouse universe." He built a large metal pen, about 9 feet square, with tall sides. It had many tunnels leading to nesting boxes, food, and water. There was always plenty of food, water, and nesting material. There were no predators. The only limit was the amount of space.

In July 1968, he put four pairs of mice into this habitat. At first, the mouse population grew very quickly. But after about 315 days, the growth slowed down a lot.

As the population grew, the mice started showing strange behaviors. They sometimes pushed their young away too early. There was more fighting and unusual social interactions. Male mice struggled to protect their areas or females. Females sometimes became aggressive. Some non-dominant males became very passive and didn't defend themselves.

After about 600 days, the social order completely broke down. Females stopped having babies. Many male mice became very withdrawn. They stopped trying to find partners or fighting. They only ate, drank, slept, and groomed themselves. These males looked very healthy and had no scars. Calhoun called them "the beautiful ones." The mice never started breeding again, and their behaviors changed permanently.

Calhoun concluded that when there's no more space and all social roles are taken, the stress causes a complete breakdown in normal social behaviors. This eventually leads to the end of the population.

Calhoun saw the fate of the mice as a possible warning for humans. He called the social breakdown a "second death." His studies are often used as a warning about the dangers of living in a world that is becoming more crowded and less personal.

See also

In Spanish: John B. Calhoun para niños

In Spanish: John B. Calhoun para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |