José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Minister of Economy of Argentina | |

| In office 29 March 1976 – 31 March 1981 |

|

| President | Jorge Rafael Videla |

| Preceded by | Joaquín de la Heras |

| Succeeded by | Lorenzo Sigaut |

| In office 21 May 1963 – 12 October 1963 |

|

| President | José María Guido |

| Preceded by | Eustaquio Méndez Delfino |

| Succeeded by | Eugenio Blanco |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 August 1925 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Died | 16 March 2013 (aged 87) Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Political party | Independent |

| Alma mater | University of Buenos Aires University of Cambridge |

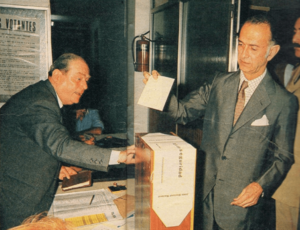

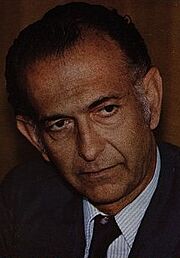

José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz (born August 13, 1925 – died March 16, 2013) was an Argentine lawyer, businessman, and economist. He served as the Minister of Economy of Argentina during a time when the country was ruled by a military government (from 1976 to 1981). He played a big part in shaping Argentina's economy during those years. He introduced new economic ideas that aimed to make the economy more open and free. These ideas are still talked about a lot in Argentina today.

Contents

Life and Career

Martínez de Hoz was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. His family was well-known for cattle ranching. He studied at the University of Cambridge. In 1955, he became the Minister of Economy for Buenos Aires Province. This happened after a change in government.

Early Role as Minister of Economy

In 1963, Martínez de Hoz became an Economy Minister during José María Guido's short time as president. Even though Argentina had returned to democracy, the military still had a lot of influence over important decisions.

Work in Private Business

Martínez de Hoz became a powerful person for Acindar, a large steel company in Argentina. He became its CEO in 1968.

Minister of Economy (1976-1981)

By 1975, Argentina was facing many problems. The public looked to the military for solutions. In March 1976, the military took over the government.

Jorge Rafael Videla became the leader and asked Martínez de Hoz to be the Minister of Economy. At this time, Argentina had very high inflation.

Economic Changes and Policies

Martínez de Hoz wanted to make businesses feel confident again. He announced a plan to open up Argentina's markets more. He believed that the country's industries were not working well enough compared to other countries. He quickly worked to lower Argentina's trade barriers. He thought these barriers made the economy too isolated.

He was friends with David Rockefeller, a famous banker. This friendship helped Argentina get large loans from banks and the International Monetary Fund.

He removed all systems that controlled prices. This helped stop black markets and shortages. He also changed rules about exchanging money. This created a single, flexible exchange rate.

He made it easier to export and import goods. He removed old rules and taxes on exports. He also gradually lowered taxes on imports.

He froze wages for workers and introduced a value-added tax. This meant people paid tax on goods and services they bought. As a result of these changes, inflation went down. However, many local shops and builders struggled and went out of business.

He also removed special prices for public services and fuel. He wanted to show the true cost of these services. He aimed to reduce special protections for certain parts of the economy.

Financial Deregulation

A year later, Argentina's trade balance improved. Business investment also grew a lot. However, people's wages could buy much less than before. Inflation started to rise again.

In June 1977, Martínez de Hoz changed the rules for financial markets. He removed checks on banks. The government then became responsible for any bad loans banks made.

The Central Bank of Argentina was led by Adolfo Diz. He helped carry out many of Martínez de Hoz's financial changes. He also made it harder to get loans within the country.

Between 1975 and 1980, Argentina's total GDP grew each year. For several years, Argentina sold more goods than it bought from other countries. The country also had very low unemployment rates during this time. However, the country's external debt grew a lot, especially after 1979.

Martínez de Hoz later explained that his plan was gradual. He wanted to change the economy's structure, not just fix a crisis. His main goals were to reduce the government's role and open up the economy.

During his time, the country's foreign debt grew four times larger. The gap between rich and poor people also became much wider. His time as minister ended with a large drop in the value of the currency. This led to one of Argentina's worst financial crises.

The "Sweet Money" Period

By 1978, Argentina was in another recession. Inflation was still very high. Martínez de Hoz was worried about possible public unrest. In December, he allowed for slightly higher wages.

To calm fears about inflation, he introduced a new system for the currency. He set a timetable for how much the Argentine peso would lose value against the US dollar each month. This was known as the Tablita.

The Tablita always made the peso lose value slower than inflation. This made imported goods and foreign loans much cheaper than local ones. Imports nearly tripled. By 1980, the peso was one of the most expensive currencies in the world. Its high value abroad made many people call it sweet money.

Many Argentines took vacations abroad and bought many appliances. However, this led to a huge loss for the country's finances in 1980 and 1981.

Many industries, especially smaller factories, could not compete with all the cheap imports. This led to many businesses going bankrupt. To try and stop job losses, Martínez de Hoz made a controversial decision. He decided that the government would take on private company debts. This included a large debt from Acindar, his former company. One of his own business interests, an electricity company, was taken over by the government at his command.

The economy seemed strong in 1979 and 1980. However, people were secretly taking out huge loans from overseas. This money was often used for risky investments. When one bank's scheme failed in March 1980, Martínez de Hoz offered special government bonds. These bonds paid high interest in US dollars.

Circular 1050 and the End of the Tablita

As his time as minister was ending, Martínez de Hoz became less popular. In April 1980, the Central Bank of Argentina made new rules for loans. These rules, called Circular 1050, tied monthly loan payments to the value of the US dollar. People thought the peso would keep losing value slowly. Many new homeowners rushed to get or refinance mortgages under these terms.

However, in February 1981, Martínez de Hoz announced a big change. The peso would lose value much faster. The Tablita system was ended. He left his position the next month.

What followed was one of the worst financial crises in Argentina's history. People who had borrowed money in US dollars suddenly faced payments that were too high. Homeowners' monthly payments, tied to the dollar, increased more than tenfold in the next 15 months.

Later Years and Legacy

After Argentina's defeat in the Falklands War in 1982, new leaders took over. In July, the new Central Bank President, Domingo Cavallo, ended Circular 1050. This saved thousands of people from financial ruin, but the economy was still badly damaged.

Businesses lost confidence in the economy. Even though Argentina's farming sector earned a lot of money from trade, it was not enough to fix the country's problems. The national debt grew from US$7 billion at the start of the military government to US$43 billion by 1983.

Martínez de Hoz faced legal issues later in life. He was arrested in 2007 and placed under house arrest due to his age. This was related to an investigation into a kidnapping and extortion case from 1976.

See also

In Spanish: José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz para niños

In Spanish: José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz para niños