José Pérez Hervás facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Pérez Hervás

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | May 23, 1880 Valencia

|

| Died | Unknown |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | Author, poet, translator, lexicographer |

| Spouse(s) | Flora Osete |

José Pérez Hervás was a Spanish writer, born on May 23, 1880, in Valencia. He was a lexicographer (someone who writes dictionaries), a translator, and a publicist. He also worked as the art director for a big encyclopedia called Espasa. José Pérez Hervás used his real name for his works, but he also wrote under different pseudonyms (pen names) like Pervás, Pimpín, Plinio «el Joven», Sávreh Zerepésoj, Singenio, Telégono, Urbi, and Flora Ossette.

Contents

Discovering José Pérez Hervás

His Early Life and Adventures

José was the youngest of three children. His older siblings were Ángela and Santiago. When he was very young, his father passed away. His mother then remarried José Sánchez Agudo, who was in charge of the Military Hospital in Bilbao. José gained two more sisters and another brother from this marriage.

After his stepfather died in 1889, José's family helped him get into the War Orphans School in Guadalajara, Spain. He joined the school in 1891.

In 1897, at 17 years old, José joined the Spanish army. He went to fight in the Philippine Revolution. After leaving the Spanish army, he joined the Philippine army to fight in the Philippine–American War. When that war ended, he spent a few years traveling around Asia. In 1901, he came back to Spain and became part of the Society of Jesus, where he worked as a teacher for several years. He left this role in 1909 and moved to Barcelona.

His Career in Barcelona

In 1910, José married Flora Osete, who was also a writer and a lexicographer. They had three daughters, Magdalena, Ángela, and Florita, and one son, José. Their three daughters formed a singing group called 'Preziossette'. This name was a mix of their parents' last names, Pérez and Osete.

While in Barcelona, José Pérez Hervás continued teaching foreign languages. He also worked in the publishing world. He was a proof-reader (someone who checks for mistakes), a translator, an author, and an art director. After working for nine years at the publishing company Montaner y Simón, he joined another publisher, Espasa, in 1917. He helped write their big encyclopedia. In 1919, he became the art director for the encyclopedia, a job he held until 1933 when all the volumes were finished.

A Disagreement with Espasa-Calpe

After the encyclopedia was completed, the team that worked on it was let go. They were offered a payment for their work, but José Pérez Hervás was not happy with the offer. He felt he deserved more.

Later, it was found that José was not only offered money but also a new job at the company, which had merged with another and was now called Espasa-Calpe S.L. in Madrid. When this new job didn't happen, he decided to create an organization. This organization was similar to a group that protects writers' and artists' rights. He wanted to show that his former employer had copied many illustrations in the encyclopedia without permission.

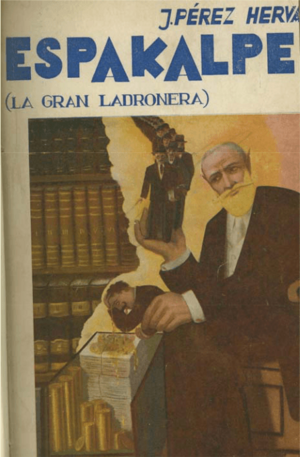

José tried to get help from other publishing groups in Madrid and Barcelona. When that didn't work, he decided to write a book. The book was meant to share details about the copyright issues with the encyclopedia's illustrations. He published the book himself in 1935. It was called Espakalpe: La Gran Ladronera, which means "The Great Den of Thieves."

In May 1935, some Spanish newspapers reported on a disagreement involving José Pérez Hervás. However, later that year, in September 1935, an advertisement for his book Espakalpe appeared in a newspaper. It seems that some kind of agreement was reached, because José Pérez Hervás was cleared of any wrongdoing. Soon after, two newspapers that had reported on the issue published a new note. They corrected some of the information they had shared earlier. One newspaper clarified that José Pérez Hervás did not leave the army to join the enemy but simply chose to stay in the Philippines when the Spanish troops left.

Because of this disagreement, the biographies of José Pérez Hervás and his wife, Flora Osete, were removed from the Espasa encyclopedia. Other content was put in their place so that the page numbers would not change. This made some people question how accurate the entire encyclopedia was, especially since it was supposed to be reprinted without changes.

His Later Years

After 1935, José Pérez Hervás spent most of his time involved in politics. During the Spanish Civil War, he worked with the newspaper Mi Revista, which was supported by the CNT and UGT unions. The last known record of his work is from 1939, when a short note advertised his commercial dictionary.

His Published Works

José Pérez Hervás wrote many different kinds of works, including poetry, novels, short stories, and essays. His work as a lexicographer (dictionary writer) is especially important. He also translated 20 books, mostly between 1911 and 1927.

Dictionaries (Lexicography)

- Gran Diccionario de la Lengua Castellana: This big Spanish dictionary was started by others and then finished and updated by Pérez Hervás and Flora Osete.

- Manual de Rimas Selectas o Pequeño Diccionario de la Rima: A small dictionary of rhymes.

- Diccionario de Correspondencia Comercial: A dictionary for business letters in Spanish, French, English, Italian, and German.

Essays

Pérez Hervás wrote many articles for newspapers and magazines. He also wrote essays that were published with some of the books he translated.

One of his most important essays was a three-volume history of the Renaissance: Historia del Renacimiento, published in 1916.

In 1935, he published Espakalpe, which we discussed earlier in the section about his disagreement with Espasa-Calpe.

Novels

- Joyas del aire, 1910.

- Brani, 1911.

- El hijo de la momia, 1913.

Short Stories

José Pérez Hervás wrote many short stories, often published in magazines like La Ilustración Artística and La Ilustración Española y Americana. Some of his stories include:

- El cirio de arroba (1910)

- La viudez de Luisa (1911)

- El hijo del verdugo (1912)

- La mismísima energía (1912)

- El llanto de Alfredo (1913)

- Mutua salvación (1913)

- La madre aviadora (1913)

- Amor perjuro (1914)

- El "Don Carlos" de la Costa (1914)

- Alma Baturra (1914)

- La Gargantilla (1915)

- La aventura de Jonás (1915)

- La Ruth alcareña (1916)

- Cosmogonía japonesa (1916)

- 'El Ama' y 'Dulcinea' (part of a book by José Sánchez Rojas, 1916)

- Las diez moneditas (1918)

- Lorito real (1918)

- La maldición de Elvira (1919)

- El padre elegido (1927)

- Alma fascista (1937)

- Sor Fai (1937)

Translations

Pérez Hervás translated many books into Spanish. Some of his translations include:

- El convite del divino amor, by Giuseppe Frassinetti (1911).

- El cerro perdido ó Un cuento de Sonora, by Thomas Mayne-Reid (1911).

- Tomás Alva Edison: Sesenta años de la vida íntima del gran inventor, by F. A. Jones (1911).

- Municipalización y nacionalización de los Servicios Públicos, by Sir John Lubbock (1912).

- Rodney Stone, by Arthur Conan Doyle (1912).

- China: dos años en la Ciudad Prohibida. Vida íntima de la Emperatriz Tzu Hsi, by Der Ling (1913).

- Los terrores del radio, by Albert Dorrington (1913).

- La mujer y el trabajo, by Olive Schreiner (1914). This translation was signed by Flora Ossette but is thought to be by Pérez Hervás.

- La isla del tesoro, by Robert Louis Stevenson (1914).

- Narraciones de un cazador, by Ivan Tugueneff (1914). This translation was said to be directly from Russian, but Pérez Hervás didn't know Russian, so it's likely he used another language version.

- El Dinamitero, by Robert Louis Stevenson (1914 or 1915).

See also

In Spanish: José Pérez Hervás para niños

In Spanish: José Pérez Hervás para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |