Kathleen M. Butler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kathleen Muriel Butler

|

|

|---|---|

Butler (standing, center) in 1924

|

|

| Born | 27 February 1891 |

| Died | 19 July 1972 |

| Known for | Sydney Harbour Bridge |

Kathleen M. Butler (27 February 1891 – 19 July 1972) was known as the "Godmother of Sydney Harbour Bridge". She was the first person to join Chief Engineer J.J.C. Bradfield's team. Her job was like a technical adviser or project manager today.

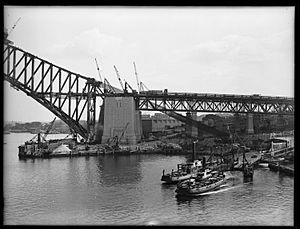

She managed the worldwide bidding process and checked the building plans. In 1924, she even traveled to London to oversee the project. At the time it was built, the Sydney Harbour Bridge was the largest arch bridge in the world. Her important and unusual role gained a lot of attention in the news.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Kathleen Muriel Butler was born on 27 February 1891 in Lithgow, New South Wales. She was one of seven children. She grew up in the Blue Mountains.

She went to school in Mount Victoria. Her father, William Henry Butler, worked there as a stationmaster. Later, she studied at Mount St. Mary's Convent in Katoomba. Butler said her mother, Annie Butler, helped her learn about engineering. Her mother was very good at drawing house plans and watching over building projects.

Kathleen Butler's Career

After leaving school, before 1910, Butler started working as a clerk and typist. She worked for Mr. W.F. Burrow in Lithgow. He was the chief officer of the New South Wales (NSW) government testing office. This office checked the quality of iron from local factories. At this time, she did not have any special technical training.

On 10 December 1910, when she was 19, she moved to the NSW Department of Public Works in Sydney.

Working with John Bradfield

In 1912, she joined the team of the Chief Engineer for metropolitan railway construction. This team was set up to fix Sydney's transport problems. This was the start of her long work relationship with J. J. C. Bradfield. She worked as his Confidential Secretary. Over the next ten years, she learned many complex engineering details. She became a very skilled technical project manager.

Bradfield first wanted to build a bridge with a cantilever design. This design would not need piers between Dawes Point and McMahons Point. In 1916, a bill to build this bridge passed one part of the government. But another part rejected it, saying money was needed for the war.

Bradfield kept working on the project. His team created full plans and a way to pay for the cantilever bridge. In 1921, Bradfield traveled overseas to look into bids for the project. He then thought they should ask for bids for both cantilever and arch bridge designs.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge Act

The important law, the Sydney Harbour Bridge Act No. 28, finally passed in 1922. This law allowed for a high-level cantilever or arch bridge across Sydney Harbour. It would connect Dawes Point with Milson's Point. The Act also included plans for the bridge's roads and electric railway lines.

Kathleen Butler had prepared the notes for this Act when it was introduced in 1921. These notes greatly helped the bill pass through the government.

When the Harbour Bridge Act passed in 1922, Kathleen Butler was the first person Bradfield hired for his team. Her job title was Confidential Secretary to the Chief Engineer. This title hid her very important role in the project. The newspapers called her the "God-Mother of the Bridge."

She was chosen because of her skills. She was involved in all parts of the project planning. She was also the main person for sharing information. She knew all the complex technical details of engineering. When the plan for the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the underground railway was approved, she worked on writing the detailed plans for building the bridge.

Butler wrote many articles about the bridge's progress between 1922 and 1927. She was like the public relations person for Bradfield's office. Copies of these articles are now kept in the Mitchell Library in Sydney.

Managing International Bids

In March 1922, Bradfield left Australia to research bridge proposals overseas. There was a delay with the Sydney Harbour Bridge Act No. 28 because of a change in government. The new government thought about canceling the project. They planned to ask Bradfield to stay in New York.

Butler knew Bradfield's travel plans. She sent him a telegram to warn him that an official telegram was coming. She told him to be somewhere else. The official telegram never reached Bradfield because he left for London.

While Bradfield was away, Butler managed all the complicated letters with international companies. These companies were bidding for the project in 1922. She was at all meetings with the bidders. She was also present when the bids were opened on 24 January 1924. She was even named in a photograph that appeared in many newspapers.

Butler, Bradfield, and engineer Gordon Stuckey worked very hard on the Sydney Harbour Bridge: report on tenders. They worked seven days a week from January 16 to February 16, 1924. Bradfield thanked Butler and Stuckey for working "cheerfully incessantly" to finish the report quickly. The report suggested choosing the British company, Messrs. Dorman, Long & Co.

Butler later said, "We were working on the report six weeks, night and day. The companies were waiting to hear their fate. We wanted them to get back to America, England, and Canada as soon as possible. I think I know that report and the specification by heart. Those were exciting days. I was the only woman present in the Minister's room when the tenders were opened. It was a most exciting moment."

Working in London

After Dorman Long was chosen in 1924, Kathleen Butler traveled to London. She sailed on the RMS Ormonde with three engineers. Her job was to set up the offices and manage the London part of the project. They worked in the Dorman Long offices.

The Australasian newspaper said, "Miss Butler is in charge of the visiting party, on £500 a year…" This was a very good salary. It was much more than her typist's salary of £110 per year in 1916. Her tasks included "attending the most difficult and technical questions... and dealing with a mass of correspondence."

Dorothy Donaldson Buchanan, the first woman in Britain to become a civil engineer, also worked on the bridge project in the same Dorman Long offices. When Bradfield joined the team in London, they visited the Dorman workshops in Middlesbrough. They went there to check on the work.

Kathleen Butler received a lot of positive attention from the news in London and Australia. Her arrival in London was in a magazine about women's rights and in gossip columns. They praised her skills and noted her interest in surfing, tennis, and dancing. The Echo newspaper said in 1924, "She is an advocate of hard work mixed with an equal part of healthy recreation."

The Woman Engineer journal called Butler a Pioneer. They said she was "the first Australian woman to take a practical interest in Engineering enterprise." She was invited to events by the Women's Engineering Society (WES). She stayed in touch with their members for several years.

Kathleen Butler left Britain on 15 November 1924. She sailed from Southampton on the SS Berengaria with Bradfield. In January 1925, her family threw her a party in Lithgow. She announced that she would "return to Sydney on Monday and on Tuesday enter in earnest on the six-years job of constructing the harbour bridge."

She was honored at a lunch in February 1925. This lunch was for professional women workers. It was hosted by Grace Scobie, Mary Jamieson Williams, and Dr. Mary Booth. These were important Australian women's rights activists.

She was present at the ceremony where the first ground was broken for the North Railway Approach to the bridge. She was publicly thanked for her work. Bradfield praised her in a paper he wrote for his university degree. Butler was also part of the Sydney University War Memorial Committee. She helped with the Memorial Carillion, representing the views of younger women.

In 1926, Butler wrote two articles for The Woman Engineer journal. These articles explained the technical progress on the Sydney Harbour Bridge. One photo showed Butler drilling the first hole into the steel for the bridge. She visited the construction site with the engineers. She even inspected the digging for the south-west skewback.

Butler got married in early 1927. Because she got married, she had to leave her job. At that time, married women were not expected to keep working. Her colleagues gave her a grandfather's clock as a gift. It was a sign of their "good will and esteem." Bradfield said that "Miss Butler's capability led to her attaining the position of trust and responsibility she held... and that her retirement would be a distinct loss to the Bridge branch."

Personal Life

On 20 April 1927, Kathleen Butler married Maurice Hagarty. He was a grazier (a farmer who raises livestock) from Cunnamulla in Queensland. They were married at St Mary's Cathedral in Sydney.

They had a daughter named Anne Josephine in 1931. Kathleen stayed in touch with the Bradfield family. She visited for the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932.

In 1936, Butler took her daughter to visit Bradfield and his wife in Sydney. She admitted she "cannot curb her interest in the new Queensland bridge at Kangaroo Point." This was the Story Bridge in Brisbane, which Bradfield was also helping to design. She felt she "hates to be out of it all."

Kathleen Hagarty died on 19 July 1972. She is buried in Macquarie Park Cemetery in Sydney.

Legacy

In 2019, a large tunnel boring machine (TBM) for the Sydney Metro was named Kathleen. This was done to honor her important work.