King of Rome facts for kids

Quick facts for kids King of Rome |

|

|---|---|

|

|

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

|

|

| Details | |

| First monarch | Romulus |

| Last monarch | Lucius Tarquinius Superbus |

| Formation | 753 BC |

| Abolition | 509 BC |

| Residence | Rome |

| Appointer | Curiate Assembly |

The king of Rome (called rex Romae in Latin) was the main ruler of the ancient Roman Kingdom. According to old stories and legends, the very first king of Rome was Romulus. He is said to have founded the city of Rome in 753 BC on the Palatine Hill.

History tells us that seven legendary kings ruled Rome. They governed the city for many years until 509 BC, when the last king was removed from power. On average, each of these kings ruled for about 35 years.

The first few kings after Romulus were not from the same family, meaning the role wasn't passed down from parent to child. It wasn't until later, after the fifth king, Tarquinius Priscus, that kings tried to make the position hereditary (passed down in the family). This attempt to create a family-based monarchy, instead of choosing kings, might have led to the creation of the Roman Republic.

Contents

Kings of Ancient Rome

Early Rome was led by a powerful ruler known as the king (rex). The king had a lot of power over the people. No one could tell the king what to do. The Senate, a group of important older citizens, had limited power. They mostly helped the king with small tasks. So, Rome was truly ruled by its king, who acted like an absolute monarch, meaning they had total control.

After Romulus, the first king, Roman kings were usually chosen by the people of Rome. This happened in a special meeting called the Curiate Assembly. A chosen member of the Senate, called an interrex, would suggest a candidate for king. Anyone could be chosen as a candidate. For example, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus was originally a citizen from a nearby Etruscan city-state. The Curiate Assembly would then vote to either accept or reject the person nominated to be king.

The king had special symbols of power. He had twelve lictors (officials who walked before him) carrying fasces (bundles of rods with an axe). He also had a special chair called a curule chair that served as his throne, a purple toga picta (a fancy robe), red shoes, and a white diadem (a type of crown) on his head. Only the king was allowed to wear the purple toga.

The king held the highest power in the state. This gave him several important roles:

The King's Main Roles

Beyond his religious duties, the king had supreme military, executive, and judicial power. This power was called imperium. The king's imperium lasted for his entire life. It also protected him from being put on trial for his actions while he was king. As the only person in Rome with imperium at that time, the king had ultimate executive power. He was also the unchecked commander-in-chief of all Rome's armies. His executive power allowed him to make decrees (official orders) that had the force of law.

The king also had the power to choose or suggest all other officials. He would appoint a tribunus celerum to lead one of Rome's tribes and command the king's personal bodyguards, the Celeres. This tribune was second in command to the king. He could also call the Curiate Assembly and suggest new laws to them.

Another important officer appointed by the king was the custos urbis, or "warden of the city." When the king was away from Rome, the warden held all the king's powers, even the imperium, within the city. The king was also the only person who could choose patricians (members of noble families) to join the Senate.

The King as Chief Judge

The king's imperium gave him military power and also made him the chief judge of Rome. He could decide all legal cases, both civil (disputes between people) and criminal. While he could ask priests (pontiffs) to act as minor judges in some cases, he had the final say in all matters brought before him. This meant the king was supreme in both war and peace. Some historians believe there was no way to appeal the king's decisions. Others think that a patrician could ask the king to reconsider a decision during a meeting of the Curiate Assembly.

To help the king, a council would advise him during trials. However, this council could not force the king to change his decisions. The king also appointed two criminal detectives (Quaestores Parricidii). He also appointed a two-man criminal court (Duumviri Perduellionis) to handle cases of treason.

The King as Lawmaker

During the time of the kings, the Senate and the Curiate Assembly had very little power. They could not meet on their own or discuss state matters unless the king called them together. They could only talk about what the king presented to them. While the Curiate Assembly could pass laws that the king suggested, the Senate was mostly an advisory group. It could give advice to the king, but it could not stop him from acting. The only thing the king could not do without the approval of the Senate and the Curiate Assembly was to declare war on another nation. Because of this, the king could mostly rule by decree, meaning he could make laws on his own, except for declaring war.

How Kings Were Chosen

Whenever a Roman king died, Rome entered a special period called an interregnum. During this time, the highest power in the state went to the Senate. Their main job was to find a new king. The Senate would meet and choose one of its own members to be the interrex for five days. This interrex would then suggest the next king of Rome. After five days, if no king was chosen, the interrex could appoint another senator for another five-day term. This process would continue until a new king was elected.

Once the interrex found a good candidate for king, he would present the person to the Senate. The Senate would then check if the candidate was suitable. If the Senate approved, the interrex would call the Curiate Assembly and lead the election of the king.

After a candidate was suggested to the Curiate Assembly, the people of Rome could either accept or reject the person. If accepted, the new king did not immediately take office. Two more important steps had to happen before he had full royal power.

First, they needed to get a sign from the gods that they approved of the new king. This was done through a ceremony called the auspices, because the king would also be Rome's high priest. A priest called an augur performed this ceremony. He would take the chosen king to a special place on the citadel (a fortress) and have him sit on a stone seat while the people waited below. If the gods gave good signs, the augur would announce it, confirming the king's religious role.

Second, the king needed to be given his imperium (supreme power). The Curiate Assembly's vote only decided who would be king, but it didn't give him the king's powers. So, the new king himself would propose a law to the Curiate Assembly to grant him imperium. The Curiate Assembly would then vote to approve this law, giving him his full authority.

In theory, the people of Rome elected their leader, but the Senate actually had most of the control over this process.

The Seven Kings of Rome (753–509 BC)

Many of Rome's old records were destroyed in 390 BC when the city was attacked. Because of this, it's hard to know for sure how many kings truly ruled Rome. It's also difficult to know if all the stories about what each king did are completely accurate.

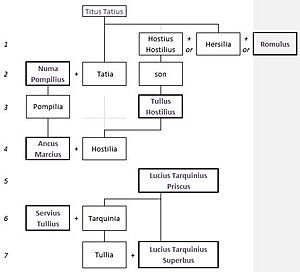

It's worth noting that Titus Tatius, the King of the Sabines, was also a joint king of Rome with Romulus for five years until he died. However, he is not usually counted among the traditional seven kings of Rome.

| Name | Birth | Reign | How They Became King |

|---|---|---|---|

| Romulus | c. 770 BC | c. 753 – 716 BC (37 years) |

Declared himself king after a dispute where he killed his brother, Remus. |

| Numa Pompilius | c. 753 BC | c. 715 – 672 BC (43 years) |

Chosen as king by the Curiate Assembly after Romulus's death. |

| Tullus Hostilius | ??? | c. 672 – 640 BC (32 years) |

Elected king by the Curiate Assembly after Numa Pompilius died. |

| Ancus Marcius | ??? | c. 640 – 616 BC (24 years) |

He was the son-in-law of Tullus Hostilius and grandson of Numa Pompilius. He was elected king by the Curiate Assembly after Tullus Hostilius's death. |

| Lucius Tarquinius Priscus | ??? | c. 616 – 578 BC (38 years) |

After Ancus Marcius died, he became a temporary ruler because Marcius's sons were too young. He was soon elected king by the Curiate Assembly. He was the first Etruscan king. |

| Servius Tullius | ??? | c. 578 – 534 BC (44 years) |

Son-in-law of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus. He took the kingship after Ancus's sons arranged for Tarquinius Priscus to be killed. |

| Lucius Tarquinius Superbus | ??? | c. 534 – 509 BC (25 years) |

Son or grandson of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus. He took the kingship after arranging the killing of Servius Tullius with his wife, who was Tullius's daughter. |

What Happened After the Kings?

The removal of the last king, Tarquinius Superbus, led to big changes in Rome. The powers that the king once held were now split up among different officials. This marked the beginning of the Roman Republic.

The actual title of "king" was kept for a religious priest called the rex sacrorum (king of sacred rites). This person was Rome's chief priest but was not allowed to have any political or military power. He could, however, sit in the Senate. The Romans wanted to make sure that no one person ever became as powerful as the kings again. So, even in religious matters, the rex sacrorum was formally less important than the pontifex maximus, who was the chief priest of Rome.

Most of the king's other powers, especially the imperium, were given to two new officials called consuls. Later, another official called a praetor was also created. The consuls were usually two people, which helped prevent one person from having too much power. In times of emergency, the power to appoint a dictator for a six-month term was introduced. This dictator would have supreme power to handle the crisis.

Over time, the power to choose new senators and remove people from the Senate, which the king once had, was given to officials called censors.

The way laws were made also changed. The Curiate Assembly lost most of its power to make laws. This power moved to other assemblies, like the Centuriate Assembly and the Tribal Assembly.

See also

- Roman emperor

- Pompilia gens

- Hostilia gens

- Marcia gens

- Tullia gens

- Tarquinia gens