Kinkaid Act facts for kids

The Kinkaid Act of 1904 was a special U.S. law. It changed the original Homestead Act from 1862. This new law allowed people to get a much larger piece of public land for free. They only had to pay a small fee.

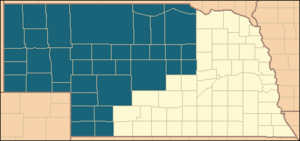

The Kinkaid Act applied to 37 counties in northwest Nebraska, especially in the Nebraska Sandhills area. Moses Kinkaid, a representative from Nebraska, introduced the act. President Theodore Roosevelt signed it into law on April 28, 1904. It officially started on June 28, 1904.

Contents

What the Kinkaid Act Allowed

The rules of the Kinkaid Act were much like the first Homestead Act.

- You had to be at least 21 years old. If you were the head of a household, you could be 18.

- You needed to be a U.S. citizen or be working to become one.

- You had to live on the land for five years to own it. This time was shorter if you served in the military.

- In 1912, the time you had to live on the land was cut to three years. This was done to get more people to settle there.

- You also had to show that you had made improvements to the land. These improvements had to be worth at least $1.25 for every acre.

Land Rules

Only lands that could not be easily watered (non-irrigable) were allowed for claims. If the government thought land could be watered, it was not included. A claim of 640 acres had to be as compact as possible. It also had to be less than two miles long. If a homesteader already owned land nearby, they could add more land to reach the 640-acre limit.

The Kinkaid Act did not allow "commutation." This meant you could not pay cash to own the land instead of living on it for the full five years. The original Homestead Act had allowed this.

People who claimed land under this act were often called "Kinkaiders." The Kinkaid Act was officially ended on October 21, 1976. The very last land ownership document under this act was given out in 1941 for 40 acres.

Why the Act Was Needed

In the late 1800s, cattle ranching was very important in the Nebraska Sandhills. Huge ranches used a lot of public land that no one had claimed yet. Ranchers would claim land that had water access. Then, they would use the public land around it for grazing their cattle.

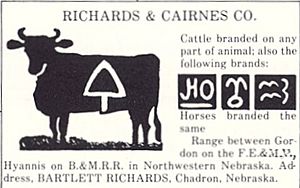

Some large ranchers used dishonest ways to get more land. They would have their workers or other people file fake homestead claims. A small shack would be built on these fake claims. The person would stay there once every six months to pretend they lived there. A common trick was to claim a thin strip of land around a large public pasture. This way, no one else could use the pasture for their cattle. It also stopped other homesteaders from claiming the land. Bartlett Richards and William Comstock, who started the Spade Ranch, were known for these kinds of actions.

The Land Problem

Because cattle ranches needed so much land, the number of people in the Sandhills actually went down by 10% between 1890 and 1900. Millions of acres of public land were still empty. To fix this, William Neville, a congressman from Nebraska, tried to pass a law in 1902. His idea was to let people claim 1,280 acres in dry, non-watered lands in the west. But his bill never became a law.

In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt said that solving the "public land problem" was a top goal. He created a Public Lands Commission in 1903 to study the issue. The commission found that the old land laws were made for wet areas. But the remaining public lands were dry. New land laws were needed for the dry lands in the western U.S.

How the Kinkaid Act Became Law

Moses Kinkaid, a congressman from Nebraska, introduced his bill on April 6, 1904. It was meant to change the homestead laws for certain unclaimed lands in Nebraska. His first idea was for homesteads of 1,280 acres. But the committee working on public lands decided to limit the size to 640 acres. They thought 640 acres would be a good starting point for dry-land farming. They believed the law could be changed later if more land was needed.

Kinkaid said his bill had three main goals:

- To get the land into the hands of individuals so it could be taxed.

- To stop the arguments and fraud over fencing and claiming land.

- To help communities grow in the region.

He said the bill was for "sandy and dry lands in western Nebraska" that were too hard to water. It specifically applied to the Sandhills region of Nebraska. Only lands that could not be watered were open for claims.

The bill passed on April 28, 1904. About 11,000,000 acres of land became available under the Kinkaid Act. Another 1,000,000 acres were held back because they might be able to be watered.

What Happened in the Sandhills Region

After the act passed, there was an immediate rush for land. One of the land offices was in Alliance. On June 28, 1904, the first day to claim land, about 400 people were waiting in line at the Alliance office. It took until June 30 to process everyone from that first day!

In April 1905, a newspaper reported that there was a building boom in Kimball County. Another newspaper in 1906 said that businesses were having their best months ever because so many new people were moving in.

Mari Sandoz, who wrote a book about living in the Sandhills, described the scene when the land first opened:

Two weeks before opening, covered wagons, horsebackers, men afoot, toiled into Alliance, got information at the land office, and vanished eastward over the level prairie. Many turned back at the first soft yellow chophills, pockmarked by blowouts and warted with soapweeds. Others kept on, through this protective border, into the broad valley region, with high hills reaching towards the whitish sky.

The number of people in the 37 counties where the law applied grew quickly:

- 1890: 124,508 people

- 1900: 107,434 people

- 1904: Kinkaid Act passed

- 1910: 162,217 people

Almost all the public lands in the region were claimed by 1912. Only very isolated or undesirable areas were left. Between 1910 and 1917, over 18,919 land ownership documents were given out for 8,933,257 acres of land.

Was it a Success?

Some people wondered if the Kinkaid Act really helped new settlers. By 1914, there were many reports that 90% of the Kinkaid claims had been taken over by large ranchers. Some argued that it was impossible to run a successful ranch with only 640 acres of land. But many of these statements came from big cattle ranchers who didn't like the Kinkaid Act in the first place.

In 1914, Moses Kinkaid told Congress that most of the claims were still owned by individual families. He said that communities in the region held many small festivals. At these events, Kinkaid homesteaders would meet and show off their farm products.

He described the average Kinkaid homesteader as a small family farmer:

They get cows, so far as they are able, and they go into dairying – those that are able to buy cattle enough to go into the stock business do so. They plow what we call the valleys ... They raise cane a good deal for feeding, and in some places alfalfa.

He guessed that the average Kinkaid homesteader had 15 to 40 cattle on their 640 acres.

A 1915 report from the Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of Nebraska supported Kinkaid's views. It found that only 200,000 acres of public land were left. There were no places left with 640 acres all together. A 1917 report from the Department of Interior looked at the first ten years of the Kinkaid Act (1904-1914). It found:

- 6,422,963 acres were held by small landowners.

- 303,553 acres were held by large landowners.

- 4,589,871 acres were still owned by the original people who claimed them.

- A total of 9,726,516 acres had been officially claimed.

The report showed that most of the land was held by small owners. About half the land was still owned by the first claimants. The report also showed that the region's economy grew:

- Cattle value increased by 34%.

- Acres planted with rye increased by 92%.

- Acres planted with oats increased by 80%.

- Acres planted with corn increased by 102%.

- Acres planted with wheat increased by 142%.

- The number of people who could vote increased by 55%.

- The total value of all property went up by 108% between 1904 and 1914. This was much more than the 17% increase from 1892 to 1904.

While the Kinkaid Act caused a quick boost in the economy, this was mostly temporary. It was hard to farm crops in the dry land on such small plots. Many Kinkaid homesteaders eventually failed at farming. They usually sold their land to large ranchers. For example, there were 377 farms in Holt County in 1913, but only 144 in 1914. This happened in many parts of the region.

The Kinkaid Act did change public land into private ownership. But its goal of filling the region with small family farms had mixed results. Government officials seemed happy with the Kinkaid Act. It became a model for other land acts in the west. These included the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 and the Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916. Since then, only very large ranches and farms have been successful on the Great Plains. Many small farms have disappeared, and some towns have become empty.

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |