Lardil language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lardil |

|

|---|---|

| Leerdil | |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [leːɖɪl] |

| Region | Bentinck Island, north west Mornington Island, Queensland |

| Ethnicity | Lardil people |

| Native speakers | 65 (2016 census) |

| Language family |

Macro-Pama–Nyungan ?

|

| Dialects | |

| AIATSIS | G38 |

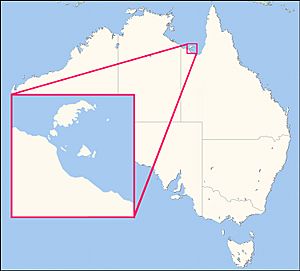

Location of Wellesley Islands, the area traditionally associated with Lardil

|

|

|

|

Lardil, also known as Leerdil or Leertil, is a special language spoken by the Lardil people. They live on Mornington Island (Kunhanha) in the Wellesley Islands of Queensland, Australia. Sadly, Lardil is a dying language, meaning very few people still speak it.

One cool thing about Lardil is that it has a secret, ceremonial language called Damin. Lardil speakers think of Damin as a separate language. It's also unique because it uses "click sounds," which are very rare in languages outside of Africa!

Contents

Lardil's Language Family

Lardil belongs to a group of languages called Tangkic. These are part of the larger group of Australian Aboriginal languages. Other languages in the Tangkic family include Kayardild and Yukulta. These two are so similar that people speaking one can often understand the other.

Lardil isn't quite as similar to Kayardild or Yukulta. However, Lardil speakers often knew Yangkaal, a language very close to Kayardild. This is because the Lardil people often met and traded with the nearby Yangkaal tribe. They also had some contact with tribes from the mainland, like the Yanyuwa and Garawa people.

Saving the Lardil Language

The number of people who speak Lardil has dropped a lot over the years. In the late 1960s, a researcher named Kenneth Hale worked with many Lardil speakers. Some were fluent older people, while younger ones had a basic understanding.

By the 1990s, another researcher, Norvin Richards, found that Lardil children no longer understood the language. Only a few older speakers were left. Richards said that Lardil was "deliberately destroyed." This happened because of programs that forced Aboriginal children to leave their families and culture. This sad period is known as the "Stolen Generation".

Despite this, there are efforts to save the language. In 1997, a dictionary and grammar guide for Lardil were created. The Mornington Island State School also has a program to teach Lardil language and culture. The last person who spoke the old form of Lardil fluently passed away in 2007. However, a few people still speak a newer version of the language.

Understanding Family in Lardil

The Lardil language has a very detailed system for family words. This shows how important family connections are in Lardil society. Everyone in the community is called by a family term, as well as their name.

For example, there are special words for pairs of people, not just individuals. One word, kangkariwarr, means "a pair of people where one is the great-uncle/aunt or grandparent of the other." This shows how specific their family terms can be!

Special Initiate Languages

In the past, young Lardil men went through two special initiation ceremonies: luruku and warama.

During the luruku ceremony, young men took an oath of silence for a year. They learned a sign language called marlda kangka, which means 'hand language'. This sign language was quite complex and had its own ways of classifying things. For instance, it had a sign for all shellfish, which Lardil itself doesn't have. Marlda kangka was also useful for hunting and fighting.

While marlda kangka was mainly for men, others could use it. But Damin, the other special language, was meant to be secret. Only warama initiates and those preparing for the second ceremony were supposed to speak it. Damin had different sounds and words from Lardil, but its grammar was similar. Research into Damin has been a bit tricky because the Lardil community sees it as their cultural property, and they didn't always give clear permission for its words to be shared publicly.

Words for the Deceased

In Lardil culture, people talk about death in a gentle way. For example, they might use the phrase wurdal yarburr, which means 'meat', when talking about someone who has passed away. Saying Yuur-kirnee yarburr ('The meat/animal has died') is a polite way to say "You-know-who has died." It's much preferred over saying it directly.

It's also considered disrespectful to say the name of a person who has died. This taboo can even apply to living people who have the same name for about a year after someone's death. These living people are then called thamarrka. Sometimes, a deceased person is known by the name of their death or burial place with the ending -ngalin. For example, Wurdungalin means 'one who died at Wurdu'. People might also use family terms to refer to the dead without saying their name.

How Lardil Sounds

Lardil has a unique set of sounds, especially its consonants. Like many Australian languages, it doesn't really tell the difference between sounds like 'p' and 'b' or 'k' and 'g'. It has many different places where sounds are made in the mouth, using the tip of the tongue or the flat part of the tongue.

Lardil also has eight different vowel sounds. What makes them different is how long you hold them. For example, waaka means 'crow', but waka means 'armpit'. The length of the vowel changes the meaning! Long vowels are held for about twice as long as short ones.

When you say a Lardil word, the main stress usually falls on the first part of the word. In a sentence, the main stress is usually on the last word.

Lardil Grammar Basics

Lardil grammar has some interesting features.

Types of Words

Lardil words can be grouped into different types:

- Verbs: These are action words, like 'run' or 'eat'. They can be simple actions or actions that affect something else.

- Nominals: This is a broad group. It includes regular nouns for things, people, or ideas. But it also includes words that act like adjectives, describing things, like kurndakurn 'dry' or durde 'weak'. Even words for time and place, like dilanthaarr 'long ago' or bada 'in the west', are part of this group.

- Pronouns: These are words like 'I', 'you', 'he', 'she', 'we', 'they'. Lardil has a very rich pronoun system. It even has special pronouns that show if people are from alternating generations (like grandparent/grandchild) or consecutive generations (like parent/child).

| Harmonic (alternating generations) | Disharmonic (consecutive generations) | |

|---|---|---|

| I | ngada | |

| You (singular) | nyingki | |

| He/She/It | niya | |

| We two (excluding you) | nyarri | nyaan |

| We two (including you) | ngakurri | ngakuni |

| You two | kirri | nyiinki |

| They two | birri | nyiinki |

| We (many, excluding you) | nyali | nyalmu |

| We (many, including you) | ngakuli | ngakulmu |

| You (many) | kili | kilmu |

| They (many) | bili | bilmu |

Word Endings (Morphology)

Lardil uses many different endings on words to change their meaning. This is called morphology.

Verb Endings

Verbs in Lardil get different endings to show things like:

- Future actions: An ending like -thur shows something will happen.

- Actions happening at the same time: A special ending marks a verb in a sentence when its action happens at the same time as the main action.

- Actions to avoid: The ending -nymerra shows that an event is not wanted. For example, niya merrinymerr means 'He might hear (and we don't want him to)'.

- Negation: To make a verb negative (like 'not do'), Lardil uses a complex set of endings.

Verbs can also get endings to show if an action is repeated, if it's done to oneself, or if it makes something else happen. You can even turn verbs into nouns by adding suffixes like -n, for example, werne-kebe-n means 'food-gatherer'.

Noun Endings (Cases)

Lardil nouns change their endings depending on their role in a sentence. This is called "case."

- Nominative case: This is the basic form of a noun, used for the subject of a sentence or the object of a simple command. It doesn't have a special ending.

- Objective case: This ending (-n ~ -in) marks the object of a verb or the person doing the action in a passive sentence.

- Locative case: This ending (-nge ~ -e ~ -Vː) shows location, like 'at', 'on', or 'in'. For example, barnga 'stone' becomes barngaa 'on the stone'.

- Genitive case: This ending (-kan ~ -ngan) shows possession (like 'my' or 'of the woman'). It also marks the person doing the action in passive sentences in the future.

- Future case: The object of a future verb gets a special ending (-kur ~ -ur ~ -r).

Ngada

1SG(NOM)

bulethur

catch+FUT

yakur.

fish+FUT

'I will catch a fish.'

This ending also marks the location for a future action or the object of a verb that shows something to be avoided.

- Non-future case: The object of a non-future verb gets the ending (-ngarr ~ -nga ~ -arr ~ -a). This is also used for time words in non-future sentences.

Lardil also has other special endings that act like cases but are attached to verbs. These can show movement to or from a place, desire, or if something is with or without something else.

Sentence Structure (Syntax)

Because Lardil uses so many word endings to show meaning, the order of words in a sentence can be quite flexible. However, the most common order is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO). This means the person or thing doing the action comes first, then the action, then the person or thing receiving the action.

Unlike most other Aboriginal Australian languages, Lardil is not an "ergative" language. In an ergative language, the subject of a simple action verb is treated differently from the subject of a verb that affects something else. In Lardil, the subject of both types of verbs takes the same basic form (nominative case).

For example:

Ngada

I

kudi

saw

kun

a

yaramanin

horse.

'I saw a horse.'

Here, 'I' (Ngada) is the subject, and 'horse' (yaramanin) is the object.

Pidngen

woman+NOM

wutha

give

kun

EV

ngimpeen

2SG(ACC)

tiin

this+ACC

midithinin

medicine+ACC

'The woman gave you this medicine.'

Here, 'woman' (Pidngen) is the subject, and 'you' (ngimpeen) and 'medicine' (midithinin) are objects.

Even when something is done to you (passive voice), the person or thing receiving the action is still the subject, and the person doing the action is the object.

Ngithun

1SG(ACC)

wangal

boomerang+ACC

yuud

PERF

wuungii

steal+R

tangan

man+ACC

'My boomerang was stolen by a man.'

Here, 'my boomerang' (Ngithun wangal) is the subject, and 'man' (tangan) is the object.

New Lardil Language

While very few people still speak the traditional form of Lardil, researchers like Norvin Richards and Kenneth Hale also studied a "New Lardil" in the 1990s. This newer version has lost some of the complex word endings found in the older language.

For example, in New Lardil, the object of a future verb might not get the special future ending it used to. Also, some of the ways to make verbs negative have become simpler. This shows how languages can change and simplify over time, especially when fewer people speak them.

See also

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |