Leadville miners' strike facts for kids

The Leadville miners' strike was a big protest by miners in Leadville, Colorado. They were upset because some silver mines were paying less than $3.00 a day. The strike started on June 19, 1896, and ended on March 9, 1897. It was a tough loss for the miners' union, called the Cloud City Miners' Union. This was mainly because the mine owners worked together against them. This defeat made the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) leave the American Federation of Labor (AFL). It also pushed the WFM to become more radical in their ideas.

Silver was found in Leadville in the 1870s, which started a big silver boom in Colorado. The strike happened when the mining industry was growing fast and becoming more organized. Mine owners became very powerful. They wanted to stop the strike and even get rid of the union completely. The local union lost the strike and almost disappeared. This was a major turning point for the WFM.

After the strike, miners had to rethink their plans and union beliefs. The WFM had started after a tough fight and had even used dynamite in another strike. But they still hoped to work things out peacefully with employers. After the Leadville strike, WFM leaders decided to use more aggressive methods. They broke away from the more traditional American Federation of Labor (AFL).

Contents

History of the Leadville Miners' Strike

The local union in Leadville was called the Cloud City Miners' Union (CCMU). It was Local 33 of the Western Federation of Miners. The Leadville strike was the first big challenge for the WFM. It was also the first time the WFM spent a lot of money and effort on a strike. Just two years earlier, the WFM had won a strike in Cripple Creek, Colorado. So, the Leadville strike was a chance for miners to gain more power and grow their union.

Changes in Mining Work

Many miners who worked deep underground came from different backgrounds. Over time, simple surface mining changed to deep underground mining. This happened from 1860 to 1910. Miners had to learn new skills and follow stricter work rules. This caused a lot of tension.

By 1900, more than 4,000 miners worked in Leadville. Mining was very dangerous. In the 1890s, almost six out of every thousand miners in Colorado died each year. This number might have been even higher for those working deep underground.

Before the 1890s, many mines were owned by the miners who found them. These owners often understood the miners' problems. But industrialization made mining much more expensive. By the 1890s, typical mine owners were bankers or businessmen. They had often never been inside a mine. Their main goal was to make money. Deep mining needed a lot of money. Investors from other parts of the country and even Europe were encouraged to invest.

Miners felt they were treated unfairly. For example, in 1894, a Leadville mine owner delayed payday for miners. He did this so he could pay money to his investors instead. The WFM wanted an eight-hour day for workers since it started in 1893. Some miners already had shorter hours. Public workers in Denver had won the eight-hour day by 1890. But in 1896, some engineers in Leadville still worked twelve-hour shifts. Deeper mines were more dangerous. People started to realize that long hours and bad conditions could harm miners' health.

Why Miners Went on Strike

In 1893, the price of silver dropped. To deal with this, mine owners cut miners' wages from $3 a day to $2.50 a day. By 1896, most miners were back to earning $3 a day. But about one-third of the workers were still getting only $2.50.

In May 1896, the CCMU asked mine owners to raise everyone's pay back to $3 a day. The union felt this was fair. Miners had lost 50 cents a day during the tough times of 1893.

Some people thought it was a bad time to ask for more money. The economy had not fully recovered. One owner said, "we have not made a dollar in two years." But others noticed that by 1895, Leadville mines were making more money than they had since 1889. Leadville was Colorado's busiest mining town, producing almost 9.5 million ounces of silver. Mine owners were actually doing better than they let on. Some owners were even planning to expand their mines and buy expensive things for their homes.

The Strike Begins

On May 26, 1896, a union group met with mine managers. They asked for the $3 daily wage to be given to all workers. But all the managers said no. From the start, owners refused to admit they were talking to union representatives. They only said they were meeting with miners. On June 19, the union committee met with managers again. They were refused again, though some managers said they would think about it. That evening, about 1,200 miners voted to strike. The strike began that night. By the next day, 968 miners had stopped working, closing many mines.

The mine owners fought back by closing all other Leadville mines. This is called a lockout. By June 22, the whole mining area was shut down. About 2,250 miners were out of work. The owners even turned off the water pumps, letting the mines fill with water. This showed they were ready for a long strike.

Who Was Involved in the Fight

Many miners in the West trusted the Western Federation of Miners. They believed it was the best group to stand up to rich and powerful business owners. But the mine owners had many advantages. Only a very strong union could win against such powerful opponents.

The Mine Owners

On June 22, the mine owners agreed to the lockout. They also secretly signed an agreement to stick together against the union. They promised not to recognize the union or negotiate with it. They also agreed not to make any deals unless most owners voted for it. This secret plan was later revealed by the Colorado State Legislature.

Leadville city officials supported the mine owners. So, the owners had the help of the city police and most local businesses. The Leadville police sided with the mine owners. However, the sheriff of Lake County supported the union.

Mine owner John Campion hired spies from detective agencies like Thiel and Pinkerton. These spies watched the union. Campion even hired more spies to watch new workers brought in from other states. The owners had a good spy network. They knew all about the union's plans, ideas, and feelings of its members. They not only locked out workers but also created a blacklist. This meant they kept a list of union members so they wouldn't be hired. They also tried to cause problems within the union. When their spies found disagreements among strikers, they used them to their advantage.

In an earlier strike in Idaho, mine owners had said they accepted unions. But in Leadville, owners acted like unions had no right to exist. They refused to use the word "union." They sent messages to "miners," not to their organization. Some owners even threatened to flood nearby mines by turning off their water pumps. This would stop those mines from meeting union demands.

The Miners' Union

In 1896, some people thought the WFM was very radical. But the WFM actually wanted simple things. They wanted fair wages paid in real money, not company coupons. They also wanted health care for miners and limits on cheap immigrant labor. They hoped for peaceful talks with employers. The WFM was not ready for how determined and powerful the mine owners would be.

The Cloud City Miners' Union faced a huge challenge. Their enemies were rich and powerful. They could afford to close mines for months. Miners also lost their ability to get credit from local stores.

The union had internal problems that grew worse during the strike. Different nationalities and ideas about unions caused trouble. They also didn't have enough money. Some members didn't trust the union leaders. They were also suspicious of outside union staff who earned more than the strike pay miners received. Most members were Irish-American, and they elected mostly Irish-American leaders. Other groups, like the Cornish, were unhappy about this. They thought the Irish leaders favored Irish miners. Local leaders sometimes had to force some ethnic groups to stay loyal.

The mine owners used spies to watch and weaken the union. Spies sent thousands of daily reports about the CCMU's inner workings. They reported on its disagreements, plans, and weaknesses. Everyone knew there were spies. Details of secret union meetings even appeared in the local newspaper the next day. But no one knew who the spies were. Spies were even given jobs to find other spies. They reported on arguments between union members. They told the mine owners about those who were loyal, those who were giving up, and those who wanted to fight.

Most mines were outside the city, so the Lake County sheriff was in charge. The sheriff was a WFM member. So were 40 of his 43 deputies. Mine owners complained that armed union groups threatened workers at the mines. They said the sheriff did not protect them from union actions.

Three Months of Waiting

Both the union and the owners refused to give in. The union leaders would not compromise with the mine owners. In July 1896, a state labor official asked the union to try to settle things peacefully. But they said, "No; we have nothing to arbitrate." The union members thought the mine owners would eventually give up one by one. They did not know about the owners' secret agreement to stick together.

The strike faced problems from the start. Other WFM unions sent money. But the AFL, which the WFM was part of, refused to help. They would not send money or ask other unions to join the strike.

On July 16, 1896, Peter Breene, who owned part of the Weldon mine, took control of it. He reopened the mine and paid $3.00 a day. The other Weldon mine owners went to court. The court agreed to put someone else in charge. But it ordered that person to keep paying $3.00 a day. Miners celebrated, thinking other mines would soon follow.

On August 13, the mine owners offered to raise the daily wage to $3. But only if the price of silver was $0.75 or more per ounce. This would not have meant an immediate pay raise. The price of silver was lower at the time. Still, after almost two months of striking, some miners found the offer tempting. Most strikers already earned $3 a day. They had nothing to gain personally from the strike. Even some $2.50-a-day miners thought $2.50 was better than no pay at all. But when union members arrived for a meeting on August 17 to discuss the offer, the union hall was locked. The union leaders had canceled the meeting without telling anyone. Some union members saw this as proof that leaders wanted to continue the strike no matter what the members thought.

Some suspected that union leaders cared more about themselves than the members. This was made worse because outside union organizers were paid $5 a day during the strike. Local leaders were paid $4 a day. This was more than the miners made.

After the CCMU leaders rejected their offer, the mine owners announced a deadline. If miners did not return to work by August 22, they would reopen the mines. They would bring in new workers if needed.

In July, the union had received 100 rifles. They gave some to county deputies and the rest to union miners. Striking miners used these rifles to form groups called "regulators." They watched the train station and stagecoaches. They tried to scare away new workers with threats or force. There were reports of attacks on new workers. Some arrests were made, but no one was found guilty. Victims could not identify their attackers. A British journalist described the situation: "No surrender; no compromise; no pity. The owners mean to starve the miners to death; the miners mean to blow the owners to atoms."

Soon, some mines reopened, including some that paid $2.50 a day. Sources disagree on whether these mines used mostly new workers from out of state or Leadville miners returning to work. Some miners quit the strike and went back to work. Their numbers grew during the strike. About 1,000 miners left Leadville to find jobs elsewhere.

At the request of a judge, the owners delayed reopening mines for one week. But talks went nowhere, and mines started to reopen. The Coronado mine was the first, with 17 men. The Emmett mine also reopened.

The Bohn mine reopened on September 4. But it closed after a few days when its workers were threatened and beaten.

Since early August, mine owners had asked Governor Albert McIntire to send in the National Guard. They wanted protection against attacks on mines and new workers. They accused Sheriff M. H. Newman, a union member, and his deputies of letting union groups threaten and attack workers. The sheriff denied this. He said the situation was under control. Without a request from the county's top law official, the governor refused to send troops. Governor McIntire was seen as somewhat supportive of workers. He felt some sympathy for the strikers. He also defended workers' right to stop working.

Attack on the Coronado Mine

On September 16, 1896, union leaders told members to "be careful and keep sober and keep out of mischief." The next day, the union said that "any violation of the law or disturbance of the peace by any member of this union endangers the success of our cause."

Just four days later, around 1 AM on September 21, 1896, about 50 armed strikers attacked the Coronado mine. It was inside Leadville city limits. About 20 armed new workers were at the mine. The attackers wanted to get close enough to destroy the building with bombs. They threw three dynamite bombs and several fire bombs. Around 1:45 AM, the oil tank for the boiler broke. The spilled oil caught fire, forcing the defending workers to run away. Flames destroyed the building. The attackers then shot and killed a fireman trying to put out the fire. The miners working at the Coronado mine killed two of the attackers and badly wounded a third.

The attackers then moved to the Emmett mine, about half a mile away. There, they used dynamite, gunfire, and a homemade cannon. The cannon made a hole in the defensive wall. The attackers tried to rush in but were pushed back by gunfire. They tried to break the boiler fuel tank at the Emmett, but failed. The attackers finally left, leaving one of their own dead from gunfire. The El Paso and R.A.M. mines were also attacked that night, but without injuries or damage. All four attackers who died were identified as WFM members.

The attacks, especially using the homemade cannon, suggested careful planning. The fact that the four dead attackers were union members, and had rifles bought by the CCMU, led many to believe union leaders were responsible. Arrests quickly followed. Ed Boyce, the national WFM president, was arrested. So were the local CCMU officers. A grand jury later charged two miners. The district attorney later admitted he had no proof against the union officers, and charges against them were dropped.

WFM President Boyce said the union was not involved in the attacks. He even accused the mine owners of hiring the attackers themselves.

National Guard Arrives

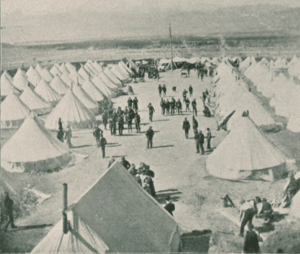

On the morning of the Coronado mine attack, Sheriff M. H. Newman, who supported the union, asked Governor McIntire to send the Colorado National Guard right away. A pro-union judge also asked for troops. With even union-friendly officials saying the situation was out of control, the governor had no choice. The first 230 guard troops arrived on September 21. By September 22, there were 653 guardsmen protecting the mines. Governor McIntire told the general to be fair and "Protect all parties alike from violence." But the presence of troops was exactly what the mine owners wanted.

WFM leader Ed Boyce was one of twenty-seven union men put in jail during the strike. Union leaders were charged, but the charges were dropped because there was no proof. Even though the attacks were not proven to be ordered by union leaders, the union was still hurt. With soldiers protecting new workers, the strike eventually failed.

The day after the Coronado mine attack, Leadville's mayor, Samuel Nicholson, announced he would hire more police. The police force, especially the new officers from Denver, were against the strikers.

Before the troops arrived, mine owners had been looking for workers outside the state. But they had not brought in new workers yet. Those who had arrived earlier were individual miners looking for jobs. But with the National Guard stopping violence, the owners easily brought in non-union miners from Missouri. The first group of 65 miners from Missouri arrived on September 25. Another group of 125 arrived on October 30. With the National Guard stopping violence, the strikers were sure to lose.

On December 26, 1896, a union miner named Patrick Carney was attacked outside his house by four new workers from Missouri. One of them shot Carney, killing him. The four were arrested but found not guilty in a trial.

In January 1897, a Leadville policeman shot and killed striking miner Frank Douherty outside a saloon. Witnesses disagreed on who shot first. The policeman claimed self-defense and was found not guilty. Dougherty was the last of six union men who died during the strike. They died either by police, new workers, or in mysterious ways.

Even though it was clear the strikers could not win, the CCMU members voted against a management offer in January 1899. This made more miners who thought the strike was lost feel discouraged. Also, the Butte, Montana WFM union, which had sent a lot of money to Leadville, sharply cut its financial help on February 2. They were apparently unhappy that the Leadville union had rejected the offer.

By February 1897, CCMU leaders admitted they had run out of money. They knew the strike was lost. Even WFM president Ed Boyce and labor activist Eugene Debs told the CCMU to accept any terms they could get. On March 5, the union members voted to accept peaceful talks. The decision went against them. On March 9, 1897, the union voted to return to work at the old wage. It was a complete defeat for the union.

What the Strike Meant for Miners

Miners in the CCMU learned two very different lessons from the strike. Some thought the union had been too stubborn. They believed the union should have taken what they could get from the owners. But others thought the union had not been radical enough. They felt a strike could not be won by following the existing laws. The group that thought the union was too aggressive often left the union. Those who thought the union had been too law-abiding, including most of the local and national leaders, tended to stay. This split left the Leadville miners' union much smaller but also much more radical. The national leadership also became more radical. WFM leader Ed Boyce suggested that each local union should have a trained "rifle club." These clubs would be able to fight local police and state soldiers.

When the WFM started in 1893, it shared the AFL's traditional views. But its experiences fighting against mine owners and their allies convinced the WFM that being peaceful would not achieve anything. Many union members started to rethink their ideas about fighting and violence. By the late 1890s, the WFM believed it had to directly confront mine owners. The WFM even thought about creating rifle clubs for certain members.

Miners in the WFM realized that their old way of organizing could not compete with the power of the wealthy. They concluded that employers' interests were "always against" the union's interests. The AFL ("organized labor of the east") could not help with the unique problems of western miners. The solution was to organize western workers and unions into a new, larger group. These ideas meant a complete rejection of the AFL's traditional and calm approach.

WFM's Relationship with Other Groups

The WFM had joined the American Federation of Labor (AFL) hoping for a lot of money and support. The WFM also hoped the AFL would ask its members to support WFM strikes if needed. During the Leadville strike, WFM President Boyce went to ask AFL leader Samuel Gompers for help. But he was refused. The AFL did not give money or ask its other unions in Leadville to support the CCMU. AFL president Samuel Gompers refused to help because he thought the local union leaders were striking for socialist reasons.

Boyce later found common ground with Eugene V. Debs, a former railway union leader. Debs had become a socialist after a big strike in 1894 was stopped by the government.

WFM's Relationship with Government Officials

During the WFM's first big strike in Cripple Creek just two years earlier, Colorado Governor Davis Hanson Waite, a Populist, sent the Colorado National Guard to protect strikers. This action encouraged working-class people to support Populists. However, fear of union actions, especially after the WFM's successful Cripple Creek strike, helped remove Populists from power. Later, the unfriendly actions of both Democratic and Republican officials during the Leadville strike made some workers distrust both major political parties.

In 1899, CCMU members formed a part of the Socialist Labor Party. A western group of unions called the Western Labor Union, formed by the WFM and other western unions in Salt Lake City in 1898, supported socialist candidates. They also called for an end to the wage system. While most WFM members did not specifically support socialism, they passed resolutions that made them seem radical and revolutionary.

Legacy of the Strike

WFM leaders and members realized they needed to build a stronger organization. To do this, they got rid of the "conservative and divisive self-interest" that had marked the AFL and western miners' groups until then.

The Leadville strike had removed miners who were against the union's goals or did not fully support them. The members who stayed agreed that they were in a class struggle. This meant they needed to be more aggressive and confrontational. Employers had set the old rules for the fight. But after Leadville, the union no longer believed those rules applied. Many WFM members were moving beyond simple reforms. They realized that to get the fair solutions they wanted, the whole system needed to change. In a document called the November 1897 proclamation, the union miners promised to start a new union group. This group would show their growing class consciousness.

The Leadville strike set the stage for the WFM to consider aggressive tactics and become more radical. It also led to the creation of the Western Labor Union (which later became the American Labor Union). The WFM also helped start the Industrial Workers of the World.

The WFM's radical views and aggressive methods did not always work. "By the early 1910s, the Federation was no longer the main champion of western workers' rights and radical ideas."

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |