Linnaean Society of New England facts for kids

The Linnaean Society of New England was a group in Boston, Massachusetts, that existed from 1814 to 1822. Their main goal was to learn about and promote natural history. This means they studied animals, plants, and minerals. The society created a natural history museum and also organized talks and trips for its members. Even though the society itself didn't last long, its energy and achievements helped natural history grow in the early United States.

What Was the Linnaean Society?

The Linnaean Society started on December 8, 1814. It began in the room of Dr. Jacob Bigelow. Many important people helped start the society. These included Jacob Bigelow, Walter Channing, and James Freeman Dana. John Davis was the first president.

The group met every Saturday evening. Members were divided into six different study groups. These groups focused on minerals, plants, animals, fish, insects, and other small creatures.

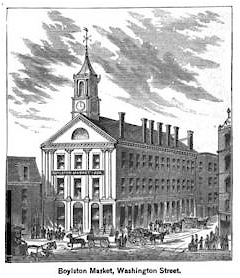

At first, the society had a room in "Joy's Buildings" in Boston. They soon moved to Boylston Market. In January 1815, they decided to call themselves the "Linnaean Society of New England." They officially became a corporation in June 1820. Many other scientists and thinkers also joined or supported the society.

Exciting Trips and Discoveries

Besides their meetings, the society also planned interesting trips. In the summer of 1816, members traveled to the mountains in New Hampshire and Vermont.

They measured the height of several mountains. They found Mount Monadnock was 3,450 feet tall. Mount Ascutney was 3,106 feet. The White Mountains reached 6,230 feet. They used special tools to measure these heights.

During these trips, they found a few interesting minerals. They also discovered three or four new types of plants.

The Society's Natural History Museum

Soon after the society formed, they announced plans for a natural history museum. They wanted to create a museum where animals, plants, and minerals could be kept. These items would be labeled with their scientific and common names. They would also be arranged by their types.

The society hoped this collection would help students. They also hoped it would teach people about the natural history of the United States.

Amazing Specimens in the Museum

The museum received many gifts. Commodore Stewart gave two living tigers. However, these tigers were somehow lost. Commodore Chauncey donated a living bear. Other gifts included Chinese insects, corals, and minerals from a volcano called Vesuvius.

They also received birds from France and Africa. There was a collection of English game-birds. A caribou was also donated. One of the most important items was a large type of deer, often called an "elk."

The museum was in Boylston Hall. It was open to the public. Visitors could enter by asking any member of the society.

The museum had many different types of animals. There were lions, tigers, leopards, wolves, bears, and deer. Many smaller animals, mostly from America, were also there.

The bird collection had almost 300 birds. These included large sea-eagles and tiny hummingbirds. Most birds were from America, but some beautiful ones came from tropical countries.

The museum also had many fish. They were prepared and displayed on a white background. There were thousands of insects and shells. These included rare and beautiful types from both America and other countries. The museum also had four large cabinets filled with minerals.

Most of the collection was kept in special mahogany cases with glass fronts. Members of the society and an artist named M. Duchesne prepared the specimens.

The Great Sea Serpent Mystery

In 1817, the society looked into reports of a strange "sea serpent." People said they saw it north of Boston, near Gloucester and Cape Ann.

Members of the society created questionnaires. They asked people what they saw. They then wrote a scientific report, which was published that same year. The report included information about a similar sea snake seen in Norway. It also described a smaller sea animal from Cape Ann. People thought this smaller animal might be the baby of the large sea serpent.

To explain their findings, the society created a new scientific name: Scoliophis Atlanticus. The smaller animal was shown to the public.

However, there was a lot of debate about the society's report. Some experts disagreed. A French scientist in Philadelphia said the "sea serpent" was actually a common land snake from the United States. He believed its wavy spine was caused by a disease.

Even with this debate, the editor of a Philadelphia newspaper believed the sea monster was real. Eventually, experts agreed that the Linnaean Society's findings were wrong. What they thought was a new species was actually a black snake. It was an Eastern racer, a common type of snake.

Why the Society Ended

The Linnaean Society eventually closed because its members became busy with other things. In 1822, they decided to stop their meetings. They gave up their rooms. They also decided to store their collection in a place where it would not cost them more money.

Items that could spoil, like stuffed animals and specimens in alcohol, were given to Ethan Allen Greenwood. He owned the New-England Museum.

The rest of the collection was offered to the Boston Athenaeum, but they said no. Then, it was offered to Harvard College, which accepted. However, Harvard did not follow the agreement. In 1830, the society took back its specimens. These included "a few empty glass cases, or containing old monkeys and birds." These items were then given to the new Boston Society of Natural History.