Louis-Ferdinand Céline facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

|

|

|---|---|

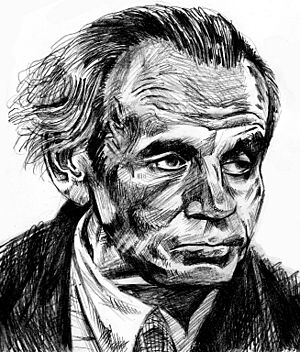

Céline in 1932

|

|

| Born | Louis Ferdinand Auguste Destouches 27 May 1894 Courbevoie, France |

| Died | 1 July 1961 (aged 67) Meudon, France |

| Occupation | Novelist, pamphleteer, physician |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse | Lucette Destouches |

| Signature | |

Louis Ferdinand Auguste Destouches (born May 27, 1894 – died July 1, 1961), known by his pen name Louis-Ferdinand Céline, was a French novelist, writer of strong opinions, and a doctor. His first novel, Journey to the End of the Night (1932), won an award called the Prix Renaudot. However, it also caused disagreements among critics because of how the author showed a sad view of human life and used a writing style based on how working-class people spoke. In later novels like Death on the Installment Plan (1936) and Castle to Castle (1957), Céline continued to develop his unique and new writing style.

Starting in 1937, Céline wrote several books that expressed very strong and negative views against Jewish people. In these writings, he suggested that France should form a military alliance with Nazi Germany. He kept sharing these views publicly even when Germany occupied France during World War II. After the Allies landed in Normandy in 1944, he fled to Germany and then to Denmark, where he lived away from his home country. A French court found him guilty of working with the enemy in 1951, but he was pardoned by a military court soon after. He then returned to France and continued his work as both a doctor and a writer. Céline is widely seen as one of the most important French novelists of the 20th century. However, he remains a controversial figure in France because of his strong negative views against Jewish people and his actions during World War II.

Contents

Biography

Early life and education

Louis Ferdinand Auguste Destouches was born in 1894 in Courbevoie, a town near Paris. He was the only child of Fernand Destouches and Marguerite-Louise-Céline Guilloux. His family came from different parts of France, including Normandy and Brittany. His father worked as a manager in an insurance company, and his mother owned a shop that sold old lace.

In 1905, Louis earned his Certificat d'études, which is a school certificate. After that, he worked in various jobs as an apprentice and a messenger. Between 1908 and 1910, his parents sent him to Germany and England for a year each. This was so he could learn foreign languages for future jobs. During these years, Céline worked in different places, often for jewelers. Even though he wasn't in school, he bought textbooks and studied on his own. Around this time, he started to dream of becoming a doctor.

World War I and time in Africa

In 1912, Céline joined the French army by choice. He served for three years in the 12th Cuirassier Regiment. At first, he didn't like army life, but he soon got used to it and became a Sergeant. When World War I began, Céline's unit saw action. On October 25, 1914, he bravely volunteered to deliver a message during heavy German gunfire. He was wounded in his right arm near Ypres. For his courage, he received a military medal in November. He later wrote that his war experience made him deeply dislike anything related to fighting.

In March 1915, he was sent to London to work in the French passport office. He explored the city's nightlife and later used these experiences in his novel Guignol's Band (1944). In September, he was declared unable to serve in the military and was discharged.

In 1916, Céline went to Cameroon, which was then controlled by France. He worked for a forestry company, managing a plantation and a trading post. He also ran a small pharmacy for the local people. He left Africa in April 1917 due to poor health. His time in Africa made him dislike colonialism and strengthened his desire to become a doctor.

Becoming a doctor

In March 1918, Céline worked for the Rockefeller Foundation. He was part of a team that traveled around Brittany, teaching people about tuberculosis and hygiene. He met Dr. Athanase Follet, who encouraged him to study medicine. Céline studied part-time and passed his exams in July 1919. He married Dr. Follet's daughter, Édith, in August.

Céline started medical school in Rennes in April 1920. In June, his daughter, Collette Destouches, was born. In 1923, he moved to the University of Paris. In May 1924, he finished his medical degree by defending his paper on the life and work of Philippe-Ignace Semmelweis, a famous doctor.

Work with the League of Nations and medical practice

In June 1924, Céline joined the Health Department of the League of Nations in Geneva. He traveled a lot for his job, visiting places in Europe, Africa, Canada, the United States, and Cuba. He used his experiences from this time in his play L'Église (The Church).

Édith divorced him in June 1926. A few months later, he met Elizabeth Craig, an American dancer. They stayed together for six years, during which he became a well-known author. He later said he wouldn't have achieved anything without her.

He left the League of Nations in late 1927 and opened a medical practice in Clichy, a working-class suburb of Paris. His practice didn't make much money, so he also worked at a public clinic and for a pharmaceutical company. In 1929, he closed his private practice and moved to Montmartre with Elizabeth. He continued to work at the public clinic and other medical places. In his free time, he wrote his first novel, Voyage au bout de la nuit (Journey to the End of the Night), which he finished in late 1931.

Becoming a famous writer and controversial figure

Voyage au bout de la nuit was published in October 1932 and received a lot of attention. Even though Destouches used the pen name Céline to stay anonymous, the press soon revealed his true identity. The novel was praised by some for its anti-war and anti-colonial ideas, but others criticized it for being cynical. One critic praised his use of everyday, spoken French as an "extraordinary language." The novel was a favorite for the Prix Goncourt award in 1932. When it didn't win, the scandal helped Céline's novel sell 50,000 copies in two months.

Despite his success as a writer, Céline still saw himself as a doctor. He continued working at the Clichy clinic and in pharmaceutical labs. He also started writing a novel about his childhood, which became Mort à Credit (1936). In June 1933, Elizabeth Craig returned to America for good. Céline visited her in Los Angeles the next year but couldn't convince her to come back.

Céline initially didn't want to take a public stand on the rise of Nazism in France. He told a friend in 1933 that he was an anarchist and didn't believe in politicians. However, in 1935, a British critic noted that Céline seemed ready to support fascism.

Mort à credit was published in May 1936. Many parts had been removed by the publisher. Critics were divided, with most criticizing its language and sad view of humanity. The novel sold 35,000 copies by late 1938.

In August, Céline visited Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) for a month. When he returned, he quickly wrote an essay called Mea Culpa, where he criticized communism and the Soviet Union.

In December of the next year, Bagatelles pour un massacre (Trifles for a Massacre) was published. This was a long book filled with racist and antisemitic ideas. In it, Céline suggested a military alliance with Hitler's Germany to save France from war and what he called "Jewish control." The book received some support from the French far-right and sold 75,000 copies by the end of the war. Céline followed this with Ecole des cadavres (School for Corpses) in November 1938, where he continued to develop his antisemitic ideas and support for a French-German alliance.

Céline was now living with Lucette Almansor, a French dancer he had met in 1935. They married in 1943 and stayed together until Céline's death. After Bagatelles was published, Céline quit his jobs at the clinic and pharmaceutical lab to focus on his writing.

World War II and exile

When World War II started in September 1939, Céline was declared 70% disabled and unfit for military service. He worked as a ship's doctor on a troop transport. In February 1940, he found a job as a doctor in a public clinic in Sartrouville, near Paris. When Paris was evacuated in June, Céline and Lucette used an ambulance to help an elderly woman and two babies escape to La Rochelle.

Back in Paris, Céline became head doctor of the Bezons public clinic. In February 1941, he published a third controversial book, Les beaux draps (A Fine Mess). In this book, he criticized Jewish people, Freemasons, the Catholic Church, the education system, and the French army. The book was later banned by the Vichy government for insulting the French military.

In October 1942, Céline's antisemitic books were republished. This happened just months after many French Jews were rounded up at the Vélodrome d'Hiver. During the occupation, Céline spent most of his time on his medical work and writing a new novel, Guignol's Band. This novel was a dream-like retelling of his experiences in London during World War I. It was published in March 1944 but didn't sell well.

The French people were expecting the Allies to land in France at any time. Céline was receiving death threats almost daily. Even though he hadn't officially joined any groups that worked with the Germans, he often allowed his antisemitic views to be quoted in newspapers that supported the occupation. The BBC also named him as a writer who collaborated with the enemy.

When the Allies landed in France in June 1944, Céline and Lucette fled to Germany. They ended up in Sigmaringen, where the Germans had set up a place for the French government in exile and those who collaborated. Using his connections with German officers, Céline got visas for German-occupied Denmark. He arrived there in late March 1945. These events became the basis for his post-war novels: Castle to Castle (1957), North (1960), and Rigodon (1969).

Living in Denmark

In November 1945, the new French government asked for Céline to be sent back to France for working with the enemy. The next month, he was arrested and put in prison in Denmark while the request was processed. He was released from prison in June 1947, but he was not allowed to leave Denmark. Céline's books had been removed from sale in France. He lived off gold coins he had hidden in Denmark before the war. In 1948, he moved to a farmhouse on the coast owned by his Danish lawyer. There, he worked on the novels that would become Féerie pour une autre fois (1952) and Normance (1954).

The French authorities tried Céline in his absence for actions harmful to national defense. He was found guilty in February 1951 and sentenced to one year in jail, a fine, and losing half his property. In April, a French military court gave him a pardon because he was a disabled war veteran. In July, he returned to France.

Final years in France

Back in France, Céline signed a contract with the publisher Gallimard to republish all his novels. Céline and Lucette bought a house in Meudon, a town on the outskirts of Paris, where Céline lived for the rest of his life. He registered as a doctor in 1953 and set up a practice in his home. Lucette opened a dance school on the top floor.

Céline's first novels after the war, Féerie pour une autre fois and Normance, didn't get much attention and didn't sell well. However, his 1957 novel D'un château l'autre (Castle to Castle), which told the story of his time in Sigmaringen, attracted a lot of media and critical interest. It also brought back the controversy about his actions during the war. The novel sold fairly well, with almost 30,000 copies in its first year. A follow-up novel, Nord (North), was published in 1960 and generally received good reviews. Céline finished a second draft of his last novel, Rigodon, on June 30, 1961. He died at home the next day from a ruptured blood vessel.

Controversial views and actions

Céline's first two novels did not contain any open antisemitism. However, his later books, Bagatelles pour un massacre (Trifles for a Massacre) (1937) and L'École des cadavres (The School of Corpses) (1938), are known for their strong antisemitic views. They also show Céline's support for many of the same ideas that French fascists had been spreading since 1924. While some on the French far-right welcomed Céline's antisemitism, others worried that his harshness might not be helpful. Still, one biographer concluded that Céline became "the most popular and most resounding spokesman of pre-war antisemitism" because of his fierce voice and the respect he held.

Céline continued to express his antisemitic views publicly even after France was defeated in June 1940. In 1941, he published Les beaux draps (A Fine Mess), where he sadly stated that "France is Jewish and Masonic, once and for all." He also wrote over thirty letters, interviews, and answers to questions for newspapers that supported the German occupation. These included many antisemitic statements. Some Nazis even thought Céline's antisemitic statements were too extreme and might not be helpful.

Céline's feelings about fascism were not always clear. In 1937 and 1938, he supported a military alliance between France and Germany. He believed this would save France from war and what he called "Jewish control." However, some argue that Céline's main goal was peace at any cost, rather than a strong belief in Hitler. After the French Popular Front won the election in May 1936, Céline saw the socialist leader Léon Blum and the communists as bigger threats to France than Hitler. He once said he would prefer "a dozen Hitlers to one all-powerful Blum."

While Céline claimed he was not a fascist and never joined any fascist group, in December 1941, he publicly supported forming a single party to unite the French far-right. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, he supported the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism. However, according to one expert, Céline didn't "subscribe to any recognisable fascist ideology other than the attack on Jewry."

After the war, Céline was found guilty of actions that could harm national defense. This was due to his letters to newspapers that supported the occupation. While he never joined any official committees or helped the German ambassador or Gestapo, his writings had a lasting impact on French ideas. They helped and supported antisemitism and, as a result, made people more accepting of the Germans. This cannot be denied.

Literary themes and style

Themes in his novels

Céline's novels often show a sad view of human life. He believed that human suffering is unavoidable, death is the end, and hopes for human progress and happiness are just illusions. He described a world where there is no moral order, and where the rich and powerful will always treat the poor and weak unfairly. According to one of Céline's biographers, people in Céline's stories suffer from a deep, hateful flaw, but there is no God to save them. This hatred is often without a clear reason; people hate simply because they have to.

The experience of war deeply affected Céline, and it is a theme in almost all his novels. In Journey to the End of the Night, Céline shows the horror and foolishness of war as a powerful force that turns ordinary people into animals focused only on surviving. For Céline, war is the clearest example of the evil that exists in human nature.

Another common theme in Céline's novels is the struggle of an individual to survive in a difficult world. Even though people in Céline's stories cannot escape their fate, they have some control over their death. They don't have to be killed randomly in battle. They can choose to face death, which is more painful but also more dignified.

Céline's main characters often choose to be defiant. If you are weak, you can gain strength by taking away the importance of those you fear. This attitude of defiance offers a sense of hope and personal salvation.

The narrator in Céline's stories also finds some comfort in beauty and creativity. The narrator is always moved by human physical beauty, like a beautifully formed body that moves gracefully. For Céline, ballet and ballerinas are perfect examples of artistic and human beauty. He often describes the movement of people and objects as a dance. He also tries to capture the rhythms of dance and music in his language. However, the dance is always a "dance of death," and things fall apart because death affects them.

Writing style

Céline did not like the traditional French "academic" writing style, which focused on being elegant, clear, and exact. He was a major innovator in French literary language. In his first two novels, Journey to the End of the Night and Death on the Installment Plan, Céline surprised many critics. He used a unique language based on the spoken French of working-class people, medical and nautical terms, new words, rude words, and the special slang of soldiers, sailors, and criminals. He also created his own way of using punctuation, with many ellipses (three dots) and exclamation marks. These three dots are like musical notes; they divide the text into rhythmic parts rather than just grammatical sentences. This allows for big changes in speed and helps create the dream-like, poetic feel of his writing.

Céline called his increasingly rhythmic and choppy writing style his "little music." In Fables for Another Time, Céline's anger pushes him beyond regular prose into a new language that is part poetry and part music. Céline's style changed to match the themes of his novels. In his final war trilogy, Castle to Castle, North, and Rigadoon, all worlds seem to disappear into nothingness. The trilogy is written in short, simple sentences, showing how language breaks down as reality does.

Legacy

Céline is widely considered one of the most important French novelists of the 20th century. Some experts believe that his work, along with that of Marcel Proust, shaped the way stories are told in the 20th century.

Many writers have admired and been influenced by Céline's fiction. However, he holds a unique place in modern writing because of his sad view of human life and his unusual writing style. Writers who focused on the "absurd," like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, were influenced by Céline, but they didn't share his extreme sadness or his political views. Other writers, like Günter Grass, also show a debt to Céline's writing style. American writers such as Henry Miller, William S. Burroughs, and Kurt Vonnegut were also influenced by him.

Céline remains a controversial figure in France. In 2011, the 50th anniversary of Céline's death, his name was initially on an official list of 500 people and events to be celebrated nationally. However, after protests, the French Minister of Culture announced that Céline would be removed from the list because of his antisemitic writings.

In December 2017, the French government and Jewish leaders expressed concern over plans by publisher Gallimard to republish Céline's antisemitic books. In January 2018, Gallimard announced it was stopping the publication. In March, Gallimard clarified that it still planned to publish a special edition of the books with scholarly introductions to explain their context.

A collection of Céline's unpublished writings was found in March 2020 and revealed in August 2021. These included La Volonté du roi Krogold, Londres, and 6,000 unpublished pages of works that had already been published. These manuscripts had been missing since Céline fled Paris in 1944. Experts believe it will take many years for these writings to be fully understood and published. Some have called the lost manuscripts "one of the greatest literary discoveries of the past century, but also one of the most troubling."

In May 2022, Céline's Guerre (War) was published, and Londres (London) followed in October 2022. The novel Londres was likely written in 1934 and includes a key character who is a Jewish doctor.

Works

Novels and short story

- Journey to the End of the Night (Voyage au bout de la nuit [1932])

- Death on Credit (Mort à crédit), 1936 – also known as Death on the Installment Plan

- Guignol's Band, 1944

- London Bridge: Guignol's Band II (Le Pont de Londres − Guignol's band II), published after his death in 1964

- Cannon-Fodder (Casse-pipe), 1949

- Fable for Another Time (Féerie pour une autre fois), 1952

- Normance, 1954 (Sequel to Fable for Another Time.)

- Castle to Castle (D'un château l'autre), 1957

- North (Nord), 1960

- Rigadoon (Rigodon), completed in 1961 but published after his death in 1969

- Guerre (War), Paris, Gallimard, 2022 (not yet translated)

- Londres (London), Paris, Gallimard, 2022 (not yet translated)

- Des vagues (Waves), short story, written in 1917, published in 1977 (not yet translated)

Other selected works

- Carnet du cuirassier Destouches, dans Casse-Pipe, Paris, Gallimard, 1970 (not yet translated)

- Semmelweis (La Vie et l'œuvre de Philippe Ignace Semmelweis. [1924])

- Ballets without Music, without Dancers, without Anything, (Ballets sans musique, sans personne, sans rien, (1959)

- The Church (L'Église), (written 1927, published 1933)

- Mea Culpa, 1936

- Trifles for a Massacre (Bagatelles pour un massacre), 1937

- School for Corpses (L'École des cadavres), 1938

- A Fine Mess (Les Beaux Draps), 1941 (not yet translated)

- "Reply to Charges of Treason Made by the French Department of Justice (Réponses aux accusations formulées contre moi par la justice française au titre de trahison et reproduites par la Police Judiciaire danoise au cours de mes interrogatoires, pendant mon incarcération 1945–1946 à Copenhague, 6 November 1946"

- Conversations with Professor Y (Entretiens avec le Professeur Y), 1955

- The Selected Correspondence of Louis-Ferdinand Céline

- Progrés, Paris, Mercure de France, 1978 (not yet translated)

- Arletty, jeune fille dauphinoise (scénario), Pris, La Flute de Pan, 1983 (not yet translated)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Louis-Ferdinand Céline para niños

In Spanish: Louis-Ferdinand Céline para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |