Low Moor Ironworks facts for kids

The ironworks around 1855

|

|

| Built | 13 August 1791 |

|---|---|

| Location | Low Moor, Bradford, England |

| Coordinates | 53°45′10″N 1°46′08″W / 53.752762°N 1.768988°W |

| Industry | Ironworking |

| Products | Wrought iron |

| Defunct | 1920 |

The Low Moor Ironworks was a huge factory that made wrought iron. It was built in 1791 in a village called Low Moor, which is about 3 miles south of Bradford in Yorkshire, England. The factory was built there because the area had lots of good quality iron ore and coal. This coal was special because it had very little sulphur, which is important for making strong iron.

From 1801 until 1957, Low Moor made wrought iron products that were sent all over the world. At one time, it was the biggest ironworks in Yorkshire! It was a massive place with mines, piles of coal and ore, special ovens called kilns, huge furnaces, and workshops where metal was shaped. All these parts were connected by railway lines. The area around the factory was quite messy with waste, and smoke from the furnaces often filled the sky. Today, Low Moor is still an industrial area, but the pollution is mostly gone.

Contents

Why Low Moor Was a Great Place for Ironworks

The Low Moor Ironworks was successful because of the amazing natural resources found nearby. The area had excellent coal and iron ore.

Special Coal and Iron Ore

- The "better bed" coal was found in a seam about 18 to 28 inches thick. This coal was very important because it had very little sulphur. Sulphur can make iron weak.

- Above this coal, there was another layer of "black bed" coal.

- Even higher up, there was ironstone, which is a rock that contains about 32% iron.

- Deeper down, there were more coal beds.

Around the time the ironworks started, new technologies made it possible to melt iron using coal instead of charcoal. Also, steam engines could now power the machines needed to make iron products.

How the Land Was Acquired

Most of the land for the ironworks was part of a large estate called Royds Hall. People were already digging for coal there as early as 1673. In 1744, the owner, Edward Rookes Leeds, started to dig for coal more actively. Around 1780, a wooden railway was built to carry coal from the Low Moor mines to Bradford. From Bradford, the coal could be moved using the Leeds and Liverpool Canal.

Soon after, Leeds faced financial problems. His property was offered for sale twice, but no one bought it. Leeds passed away in 1787. In 1788, the estate was sold for £34,000 to a group of partners: Richard Hird, John Preston, and John Jarratt. Later, the main partners became Richard Hird, Joseph Dawson (a minister), and John Hardy (a lawyer). Joseph Dawson was very interested in how metals and chemicals worked. He was a close friend of a famous scientist, Dr. Joseph Priestley. Dawson seemed to be the main person who pushed for the ironworks to be built.

The partners hired an engineer named Smalley from Wigan to build the main engine for the furnaces. Smalley then asked Thomas Woodcock to design the furnaces, casting houses, and other parts of the factory. Woodcock moved to Low Moor and became the main architect and general manager until he died in 1833.

Building and Growing the Ironworks

Construction of the Low Moor Ironworks began in June 1790. This included building large blast furnaces and casting shops.

First Operations and Products

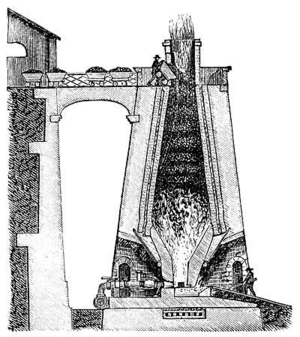

The furnaces were very tall, about 50 feet high, and had square bases that got narrower towards the top. The first two furnaces started working on August 13, 1791. Just three days later, the first iron was cast! At first, the factory made things for homes, but soon they started making parts for steam engines and other industrial products.

In 1795, the company won important contracts to make guns, cannonballs, and shells for the government. This was because Britain was at war with France. By 1799, the works were making about 2,000 tons of pig iron each year. From this pig iron, they made all sorts of things, from strong columns for building mills to garden furniture.

Expanding Mines and Railways

In 1800, the company opened the Barnby Furnace Colliery to get more coal. This mine was connected to the Barnsley Canal by the Low Moor Furnace Waggonway in 1802. This waggonway was later replaced in 1809 by the Silkstone Waggonway, which operated until 1870.

The same families who started the ironworks owned it throughout the 1800s. The amount of money invested in the company grew from £52,000 in 1793 to £250,000 in 1818. In 1801, the company started making wrought iron. At first, they used iron from other places, but by 1803, they were using their own Low Moor pig iron.

Life at the Ironworks

As the ironworks grew, the company built homes for its workers in a nearby area called North Brierley. They even built a hostel for the boys who worked in the mines. These boys received free clothing and schooling! The company also ran several local pubs.

By the end of the war with France in 1814, the works were producing 33 tons of pig iron every week. After the war, prices dropped for a while. But then, in 1822, demand for gas pipes and street lights started to increase.

A local poet, John Nicholson, wrote about the ironworks in 1829:

When first the shapeless sable ore

Is laid in heaps around Low Moor,

The roaring blast, the quiv'ring flame,

Give to the mass another name:

White as the sun the metal runs,

For horse-shoe nails, or thund'ring guns

...

No pen can write, no mind can soar

To tell the wonders of Low Moor.

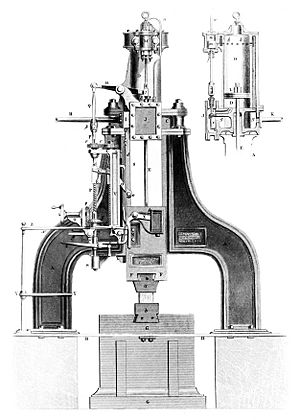

By 1835, the factory was getting more and more orders. The original site was too crowded with buildings and homes. So, they started building a new site to the southeast. In 1836, two new blast furnaces began working there. In 1842, the company installed a new mill to roll iron plates for steam engine boilers. They also added steam-powered forge hammers in 1843. In 1844, they decided to get one of James Nasmyth's brand new steam hammers.

How Iron Was Made at Low Moor

The process of turning iron ore into pig iron and then into wrought iron was quite complex.

From Coal to Coke

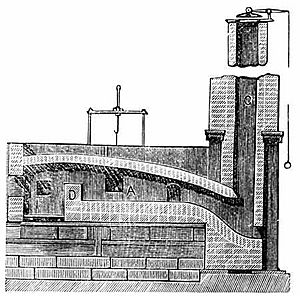

First, the coal was turned into coke. This process removed water and sulphur from the coal. It took about 48 hours if done in piles in the yard, or 24 hours if done in special ovens. About 32% of the "better bed" coal was lost during this coking process.

Preparing the Ironstone

The ironstone was left outside for some time to break it down and separate it from other rocks. Limestone was brought from Skipton to help clean the iron ore by separating clay from it. In 1832, it took a huge amount of materials to make just one ton of pig iron:

- 9,750 pounds of coal

- 2,800 pounds of limestone

- 8,500 pounds of ironstone

Melting and Shaping

The ironstone was baked with coke and limestone in a kiln. Then, it was moved into a blast furnace, where it melted into ore. This melted ore was then poured into molds to create "pigs" of iron, which had a crystal-like structure.

Low Moor had four blast furnaces, and powerful steam engines pushed air into them. The iron was then put through a process called puddling, which made it granular and easy to shape. Large steam hammers then pounded the glowing iron into flat slabs. These slabs were then rolled into wrought iron plates. A lot of the waste material, called slag, from the blast furnaces was sold to be used in building roads.

Peak Production and Global Reach

The Low Moor Ironworks became very famous for its high-quality iron.

The Famous Steam Hammer

Robert Wilson, who worked at James Nasmyth's factory, improved Nasmyth's steam hammer design. He invented a way to adjust how hard the hammer hit, which was a very important improvement. Low Moor Works was the first place to get one of Nasmyth's steam hammers. They first rejected it, but on August 18, 1843, they accepted an improved version. From 1845 to 1856, Robert Wilson worked at Low Moor Ironworks and continued to improve the steam hammer.

Exhibitions and Wars

At the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, the ironworks showed off an enormous cannon! They also displayed samples of their ore, coal, pig iron, and wrought iron, along with a smaller gun, a sugar cane mill, and an olive mill.

In 1854, the Low Moor company bought another factory called Bierley Ironworks. By 1855, Low Moor was making 21,840 tons of iron per year, making it the biggest ironworks in Yorkshire. The factories at Low Moor made many guns, shells, and cannonballs for soldiers fighting in the Crimean War (1853–56) and the Indian Mutiny (1857–58). After these wars, the government started making more of its own weapons, so Low Moor's arms business slowed down. The works then focused on making railway tires, steam engine boilers, sugar pans for factories in the West Indies, water pipes, and heavy iron parts for other industries.

A Busy Place

By 1863, there were 3,600 people working at the factory. This included 1,993 miners, 420 furnacemen, 770 forgemen, and 323 engineers. In 1864, a second steam hammer was installed for very heavy metal shaping. In 1871, a third steam hammer was added. New rolling mills were also built to make iron plates for shipbuilding. By 1867, there were about 4,000 employees!

A description of the works from that time said:

The piles of waste material from the factory actually cover the countryside, and will soon be as big as the Pyramids. In some places, the hills of rubbish have been flattened and covered with soil brought from far away... Iron plates, bars, and railway tires, sent to Russia, America, India, and, in fact, all over the world, are the main things made here; but guns (from 32 to 68-pounders) are also made here... Every small stream for miles around is blocked up to supply the works, and every drop of water is carefully saved. The huge furnaces, with wide, bright flames rising from them, of course catch your eye as you get close to the works. They look like a normal lime kiln, and on top, in the middle of the bright flames, are strange-looking wheels – parts of the machinery that pull the ironstone and other materials up a sloped track on iron wagons to the mouths of the furnaces. These wagons, working by themselves, where no person could do the job, turn upside down and unload their contents.

In 1868, Low Moor produced its highest amount of ironstone: 617,628 tons. By 1876, about 2,000 coal miners worked in pits that were 30 to 150 yards deep in the surrounding towns. Thirteen pumping engines were used to remove water from the mines. The company also employed about 800 miners in other coal mines further east. Minerals were brought to the works by horse-drawn wagons or by wagons on special tracks pulled by stationary engines.

The Low Moor mines produced about 60,000 tons of iron ore each year by 1876. The iron was highly valued for its perfect and shiny texture, and it sold for high prices. Its quality was partly due to the special ore and coal, and partly to the way it was made. However, this production came at a cost to the environment. An 1876 description said that the constant smoke made the plants look dirty. It also said that the works and its surroundings looked like the area around a volcano!

The Decline of Low Moor Ironworks

The company started to face problems in the late 1880s. Its mines were spread out and becoming more expensive to operate. The railway network had different track widths and used a mix of engines. Some of the machinery was old, and the factory was not as efficient as it could be. However, there was still a demand for "Best Yorkshire Iron" for things where safety was extremely important.

In 1888, Low Moor became a limited company, but the families who founded it still had control. The directors planned two new, taller blast furnaces at the New Works. The first one started working in 1892. In 1905, an electrical power station was built at the New Works. It used gas from the blast furnaces to power its boilers. Most of the steam-powered machines were replaced with electrical ones. When World War I (1914–1918) began, there was a sudden increase in demand for shell casings and parts for the first tanks.

After the war, it became clear that the future for wrought iron was uncertain. The company was taken over by Robert Heath & Sons, creating a new company called Robert Heath And Low Moor Ltd. They tried to cut costs, but this affected the quality of the iron. Attempts to use coal with high sulphur caused serious problems and damaged the factory's reputation for high-quality iron. Also, there was a big slowdown in heavy industry in the 1920s, which further reduced demand. The company tried to make other products, but they didn't succeed.

In 1928, the company went bankrupt. The Low Moor assets were bought by Thos. W. Ward Ltd. Many of the mines, tracks, and machines were closed or taken apart. Some buildings were sold or rented to other companies, and some machinery was updated. Wrought iron production finally stopped in 1957. By 1971, new owners were making alloy steel, producing about 350 tons per week.

Images for kids

-

James Nasmyth's patent steam hammer