Lucienne Day facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

OBE RDI FCSD |

|

|---|---|

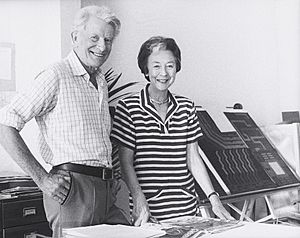

Lucienne Day with Calyx, 1951

|

|

| Born |

Désirée Lucienne Lisbeth Dulcie Conradi

5 January 1917 Coulsdon, Surrey, England

|

| Died | 30 January 2010 (aged 93) |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Royal College of Art |

| Occupation | Textile designer |

| Spouse(s) | Robin Day |

| Children | Paula |

Désirée Lucienne Lisbeth Dulcie Day (born 5 January 1917 – died 30 January 2010) was a very important British textile designer. She was active in the 1950s and 1960s. Lucienne Day was known for creating a new style of abstract patterns. This style was called ‘Contemporary’ design and became popular in Britain after World War II. She also designed wallpapers, ceramics, and carpets.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Lucienne Day was born in Coulsdon, Surrey, England. She grew up nearby in Croydon. Her mother was English, and her father was Belgian.

She first learned at home, then went to Woodford School in Croydon from 1926 to 1929. Later, she attended a boarding school in Worthing, Sussex, until 1934.

At 17, Lucienne started studying at Croydon School of Art. Here, she became very interested in designing printed fabrics. She then went to the Royal College of Art from 1937 to 1940 to focus on this field. During her studies, she worked for a company called Sanderson. She found their design style too old-fashioned for her modern taste.

Marriage and First Designs

In 1940, Lucienne met Robin Day, who would become her husband. He was a furniture designer, and they both loved modern design. They got married in 1942 and set up their home in London. Their flat was filled with Lucienne's hand-printed fabrics and Robin's handmade furniture.

During World War II, it was hard to make new textiles. So, Lucienne taught at an art school for a few years. After the war, she became a freelance textile designer. At first, she mostly designed fabrics for clothes for companies like Horrockses.

Soon, she started designing fabrics for homes. Her first big client was Edinburgh Weavers in 1949. Then, she began working with Heal's Wholesale and Export, a textile company. This partnership lasted until 1974.

In 1962, Lucienne Day became a faculty member at the Royal Designers for Industry. She was the first woman to lead this group from 1987 to 1989. After teaching, she focused more on her printed fabric and wallpaper designs.

Festival of Britain and Calyx

The Festival of Britain in 1951 was a very important event for Lucienne Day. It was a big exhibition in London where she could show off her skills. She created several textiles and wallpapers for the Homes and Gardens Pavilion.

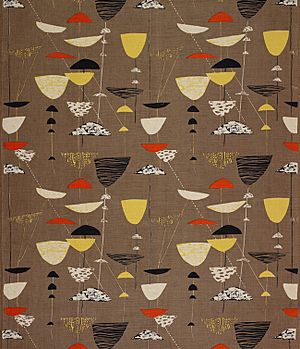

Her most famous design was Calyx. It was a fabric for a room designed by her husband, Robin Day. Calyx was hand-printed on linen with bright colors like lemon yellow, orange-red, and black on an olive background. It had a large, abstract pattern of cup-shaped designs connected by thin lines. This design looked like the work of modern artists such as Alexander Calder and Paul Klee.

Even though Heal's was unsure about Calyx at first, it became very popular and sold a lot. It also won a Gold Medal at the Milan Triennale in 1951. Calyx started a new design trend called the 'Contemporary' style, and many other designers copied it.

Lucienne also designed three wallpapers for the Festival of Britain: Provence, Stella, and Diabolo.

Textile Designs of the 1950s and 1960s

After Calyx was a hit, Heal Fabrics asked Lucienne Day to design up to six new fabrics every year. She created more than seventy designs for Heal's over 25 years. These designs are a big part of her work. They include famous patterns like Dandelion Clocks (1953), Spectators (1953), Graphica (1953), and Herb Antony (1956).

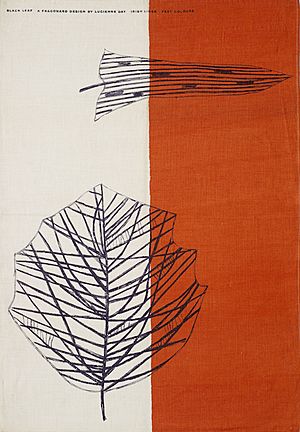

Her textiles from this time had lively rhythms and a unique, doodle-like style. They looked spontaneous but showed great skill in their colors and repeating patterns. Lucienne helped make abstract designs popular in English textiles. She often used stylized natural shapes like leaves, stems, and butterflies in her patterns.

Later in the 1950s, her designs for Heal's became more like paintings and much larger. Patterns like Sequoia (1959) and Larch (1961), which featured trees, showed a big change in her style.

In the 1960s, Lucienne used brighter colors and simpler shapes. She designed crisp floral patterns like High Noon (1965) and Poinsettia (1966). She also created striking geometric designs such as Apex (1967) and Sunrise (1969), which were similar to Op Art.

Besides Heal Fabrics, Lucienne also designed textiles for Liberty's and British Celanese. She also worked again with Edinburgh Weavers and Cavendish Textiles. Her dress fabrics for Cavendish Textiles were sold through the John Lewis Partnership.

She also designed tea towels and table linen for Thomas Somerset. Her tea towels were often playful, with designs like Jack Sprat and Too Many Cooks (1959).

Wallpapers, Ceramics, and Carpets

After designing wallpapers for the Festival of Britain, Lucienne Day continued to create them. She worked with Lightbown Aspinall, whose wallpapers were sold under the name Crown. These machine-printed wallpapers were more affordable than her earlier hand-printed ones.

Her partnership with the German company Rasch helped her reach a European audience. Her wallpaper designs were usually quieter than her textiles, with smaller patterns and simpler layouts.

Lucienne was also very active in carpet design during the 1950s and 1960s. She worked with three British companies: Wilton Royal, Tomkinsons, and I. & C. Steele. Her first carpet design, Tesserae, won a Design Centre Award in 1957. She also chose colors for Wilton Royal's Architects Range and created her own collection of bold geometric designs in 1964.

It is common for designers to work internationally today, but it was rare after the war. Lucienne was one of the few who did. She designed tableware patterns for the German ceramics company Rosenthal starting in 1957.

Design Partnerships

In 1952, Lucienne and Robin Day moved to a new house in Chelsea. They made their Victorian home a great example of ‘Contemporary’ design. Their house was shown in many magazines. The ground floor was their shared studio for almost fifty years. They rarely worked together, except for their consulting jobs.

They were design consultants for BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation) from 1961 to 1967. They designed the interiors for airplanes, including the VC10. Lucienne chose fabrics, carpets, and paint colors. She also designed patterns for the walls and window areas inside the planes.

From 1962 to 1987, they were also design consultants for the John Lewis Partnership. They helped create a new 'house style' for the company. This style covered everything from store interiors to stationery and packaging. They also developed a similar plan for Waitrose supermarkets.

Silk Mosaics and Later Years

In 1975, Lucienne Day decided to stop industrial design. She felt out of touch with the new styles. She found a new way to be creative by making unique silk mosaic wall hangings. These were made from small strips or squares of dyed silk, stitched together. They were brightly colored, some abstract, and some with patterns like zodiac signs. These hangings were shown in museums and theaters during the 1980s and 1990s.

Lucienne enjoyed the challenge of working with silk mosaics. She experimented with colors. She created large hangings for specific buildings, like Aspects of the Sun in 1990 for a John Lewis store. This allowed her to connect with architecture in a new way.

Lucienne Day officially retired in 2000. Plants had always inspired many of her designs. In her later life, she enjoyed botany and gardening. She passed away on 30 January 2010, at the age of 93.

Awards and Recognition

Lucienne Day won many awards during her career.

- In 1951, she won a Gold Medal for Calyx at the Milan Triennale.

- In 1952, she received an award from the American Institute of Decorators.

- In 1954, four of her Heal's fabrics won a Gran Premio at the Milan Triennale.

- In 1957, she won a Design Centre Award for her Tesserae carpet.

- She won two more Design Centre Awards in 1960 for three tea towels and in 1968 for her Chrevron fabric.

In 1962, Lucienne Day was named a Royal Designer for Industry (RDI). This award honors designers who show "sustained excellence in aesthetic and efficient design for industry." She was only the fifth woman to receive this honor. She later became the first female Master of the Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry from 1987 to 1989. In 2004, she was given an OBE.

Design Style and Inspirations

Lucienne Day's early textile designs were inspired by her love for modern art, especially the abstract paintings of Paul Klee and Joan Miró. She believed that good design should be affordable for everyone.

In 1957, Lucienne noted that a new style of furnishing fabrics had appeared after the war. She said that patterns based on flowers were less popular. Instead, abstract patterns, often in bright colors and inspired by modern painting, became common.

Even though abstract designs were her main focus, Lucienne also used plant forms in her patterns. She often included stylized leaves, flowers, twigs, and seedpods. In the mid-1960s, she experimented with bold geometric designs using squares, circles, diamonds, and stripes. Stylized flowers and tree designs remained common in her work until the mid-1970s.

In 2003, she explained that she wanted her work to be seen and used by people. She felt that people had missed interesting things for their homes during the war.

Legacy and Exhibitions

Lucienne Day had a long career that lasted for sixty years. Her textile designs from after the war are especially well-known. Her playful patterns captured the happy and hopeful feeling of the early 1950s. She was excellent in many areas of interior design.

Her work was first highlighted in a big exhibition called The New Look: Design in the Fifties in 1991. A solo exhibition of her work was held in Manchester in 1993. In 2001, Lucienne and Robin Day's work was shown together in a large exhibition in London.

After her death, an exhibition featuring the Days’ work was held in 2011. Lucienne Day's designs are kept in many public collections. The main places are The Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The Robin and Lucienne Day Foundation was started by their daughter, Paula Day, in 2012. It shares information about the Days through events and a website. In 2017, the Foundation celebrated Lucienne Day's 100th birthday with events across the country. Two main exhibitions were held: Lucienne Day: A Sense of Growth at The Whitworth Art Gallery, and Lucienne Day: Living Design at the Arts University Bournemouth. The Victoria and Albert Museum also launched an online collection of her work.

The Foundation now manages new versions of the Days’ designs. Companies like Classic Textiles, twentytwentyone, and John Lewis still produce her designs today.

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |