Lydia Koidula facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

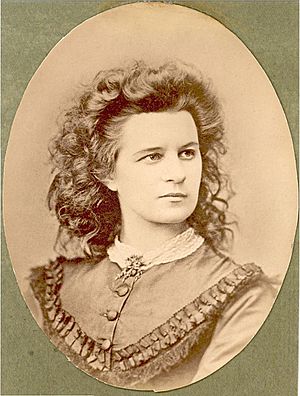

Lydia Koidula

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 24 December 1843 Vändra, Estonia (then Governorate of Livonia, Russian Empire)

|

| Died | 11 August 1886 (aged 42) Kronstadt, Russian Empire

|

| Occupation | |

| Spouse(s) |

Eduard Michelson

(m. 1873) |

| Children | 3 |

| Family | Johann Voldemar Jannsen (father) |

Lydia Emilie Florentine Jannsen (born December 24, 1843 – died August 11, 1886) was an important Estonian poet. She is best known by her pen name Lydia Koidula. Her pen name means 'Lydia of the Dawn' in Estonian. The writer Carl Robert Jakobson gave her this name. People also often called her Koidulaulik, which means 'Singer of the Dawn'.

In the mid-1800s, writing was not usually seen as a good job for young women in Estonia, or in many other parts of Europe. Because of this, Lydia Koidula's poems and her newspaper work for her father, Johann Voldemar Jannsen, were often published without her name. Even so, she became a very important writer. She is known as the founder of Estonian theatre. She also worked closely with other key figures like Carl Robert Jakobson and Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald, who wrote the Estonian national story, Kalevipoeg. Over time, Lydia Koidula became known as Estonia's national poet.

Contents

Lydia Koidula's Life Story

Lydia Jannsen was born in Vändra, Estonia. Her family moved to Pärnu in 1850. There, in 1857, her father started the first local newspaper in the Estonian language. Lydia went to a German-language school in Pärnu. In 1864, the Jannsens moved to Tartu, a city with a university.

During this time, it was difficult to express nationalism or publish in local languages in the Russian Empire. However, the ruler, Czar Alexander II, was somewhat open-minded. Lydia's father managed to get permission to publish the first Estonian-language newspaper that reached people all over the country. This newspaper, like the one in Pärnu, was called Postimees (The Courier). Lydia wrote for both of her father's newspapers and also published her own works.

In 1873, Lydia married Eduard Michelson, who was an army doctor. She moved to Kronstadt, a Russian naval base near Saint Petersburg. From 1876 to 1878, the Michelsons traveled to places like Wrocław, Strasbourg, and Vienna. Lydia Koidula lived in Kronstadt for 13 years. Even though she spent summers in Estonia, she often felt very homesick. Lydia Koidula had three children. She passed away from breast cancer on August 11, 1886. Her last poem was called Enne surma — Eestimaale! (Before death, to Estonia!).

Lydia Koidula's Writings

Lydia Koidula's most important book, Emajõe ööbik (The Nightingale of the Emajõgi River), was published in 1867. A few years earlier, in 1864, some Estonians had asked the emperor for better treatment from German landowners. They also wanted Estonian to be used in schools. This led to problems with the police and stricter rules on publishing.

Despite these challenges, Koidula began to publish her work. This was also a time of "national awakening" in Estonia. The Estonian people, who had been freed from serfdom (a type of forced labor) in 1816, started to feel proud of their nation. They began to hope for self-rule. Koidula was a strong voice for these hopes.

German culture had a big impact on Koidula's work. German people had been powerful in the Baltic region for centuries. So, German was the language used in schools and by educated people in 19th-century Estonia. Like her father, Koidula translated many German stories, poems, and plays. She was especially influenced by the Biedermeier style. This style was popular in Europe from 1815 to 1848. It was simple and focused on home, family, religion, and country life.

Koidula's early poems, Vainulilled (Meadow Flowers; 1866), showed some of these Biedermeier ideas. But her poems were also very delicate and musical. In Emajõe Ööbik, she showed strong patriotic feelings. She felt the long history of foreign rule in Estonia as a personal hurt. She wrote about "slavery" and "subordination" as if she had lived through it herself. By the 1860s, Estonia had been ruled by other countries for over 600 years. Koidula knew she had a role to play in her nation's future. She once wrote that it was "a great sin, to be little in great times when a person can actually make history."

Koidula continued the Estonian writing tradition started by Kreutzwald. But while Kreutzwald tried to copy old Estonian folk poems, Koidula wrote mostly in modern, Western European styles with rhyming lines. This made her poetry much easier for everyday people to read. Koidula's biggest impact came from her powerful use of the Estonian language. In the 1860s, Estonian was still seen as the language of farmers. It was mainly used for religious texts, farming advice, or simple stories. Koidula successfully used the Estonian language to express many feelings. She wrote a loving poem about a family cat, Meie kass (Our Cat), and gentle love poems like Head ööd (Good Night). She also wrote powerful calls to her oppressed nation, like Mu isamaa nad olid matnud (My Country, They Have Buried You). With Lydia Koidula, it became clear that the Estonian language was a rich and powerful tool for communication.

Lydia Koidula and Estonian Theatre

Lydia Koidula is also known as the "founder of Estonian theatre." She was very active in drama at the Vanemuine Society in Tartu. This society was started by her family in 1865 to promote Estonian culture. Lydia was the first to write original plays in Estonian. She also helped with directing and producing the plays.

Before Koidula, theatre was not very important in Estonia. Few writers thought drama was serious. In the late 1860s, Estonians and Finns started to create plays in their own languages. Koidula followed this trend. In 1870, she wrote and directed the comedy Saaremaa Onupoeg (The Cousin from Saaremaa) for the Vanemuine Society. This play was based on a German comedy but changed to fit an Estonian setting. The characters were simple, and the story was easy to follow, but it was very popular. Koidula then wrote and directed Maret ja Miina (also called Kosjakased; The Betrothal Birches, 1870). Her most important play was Säärane mulk (What a Bumpkin!), which was the first play ever written entirely in Estonian.

Koidula believed that theatre should teach people. Her plays were meant to educate and entertain. She worked with amateur actors, and men often played women's roles. But her plays were impressive because they had believable characters and showed real-life situations of the time.

At the first Estonian Song Festival in 1869, two of Lydia Koidula's poems were set to music. These were Sind Surmani (Till Death) and Mu isamaa on minu arm (My Country is My Love). This second song became an unofficial anthem during the Soviet occupation of Estonia. Her father's song, Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm (My Country is My Pride and Joy), was the official Estonian anthem before the Soviet occupation but was forbidden during it. Koidula's song, Mu isamaa on minu arm, was always sung at the end of every festival, even without permission. This tradition continues today.

Lydia Koidula Memorial Museum

The Lydia Koidula Memorial Museum is part of the Pärnu Museum. It tells the story of the life and work of Lydia Koidula and her father, Johann Voldemar Jannsen. Both were very important figures during Estonia's national awakening in the 1800s.

The Koidula Museum is located in the old Pärnu Ülejõe schoolhouse. This building was built in 1850 and has a unique design inside. It was once the home of Johann Voldemar Jannsen and the office for the Perno Postimees newspaper until 1863. Today, it is protected as a historical monument. Lydia Koidula grew up in this house. The museum's main goal is to keep the memory of Koidula and Jannsen alive. It shows their lives and work during the time of Estonia's national awakening.

There is also a monument to Lydia Koidula in the city center of Pärnu. It is next to the historic Victoria Hotel, at the corner of Kuninga and Lõuna streets. The monument was made in 1929 and was the last work by the Estonian sculptor Amandus Adamson. Finally, Lydia Koidula's picture was featured on the 100 krooni banknote before Estonia started using the euro.

See also

In Spanish: Lydia Koidula para niños

In Spanish: Lydia Koidula para niños