Métis Nation of Ontario facts for kids

| Abbreviation | MNO |

|---|---|

| Formation | October 2, 1993 |

| Type | Nonprofit |

| Purpose | Representing Métis people residing in Ontario |

| Headquarters | Suite 1100 – 66 Slater Street Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5H1 |

|

Region

|

Ontario |

|

Membership (2020)

|

20,000 |

|

President

|

Margaret Froh |

| Affiliations | Métis National Council |

The Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) is a government that represents Métis people and communities in Ontario. The Canadian government officially recognizes the MNO. It works to provide fair and responsible self-governance for its citizens and Métis communities in Ontario.

The Métis communities represented by the MNO are part of the larger Métis Nation. This Indigenous People developed their own unique identity, language, culture, and way of life. This happened in their historic homeland before Canada expanded westward.

Template:TOC limit=3

Contents

Exploring Métis History in Ontario

Métis people have lived in Ontario since the late 1700s. Early fur trading companies, like the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company, tried to stop their employees from forming relationships with Indigenous women. However, some men did.

While many Métis had French backgrounds, there were also many Anglo-Métis people. These were the children of Indigenous women and English or Scottish fur traders or British soldiers. These families often formed through "marriages à la façon du pays" (marriages in the custom of the country).

Métis communities began to grow around fur trading forts. Important places included Sault Ste. Marie and areas along James Bay, like Moosonee and Moose Factory.

Many Métis families had to keep their traditions private. They often tried to fit into Canadian society. However, as more settlers arrived, it became harder for them. Reserves became safe places for Indigenous peoples to practice their ways of life. This is why many Canadians today might not know about Métis people in the Great Lakes region. Despite these challenges, Métis communities survived and continue to grow in the Great Lakes area.

A very important court case in 2003, called R v. Powley, brought attention to this situation. The judge said that the Métis community had become 'invisible' but was not destroyed.

It is important to note that whether these people in Ontario called themselves "Métis" at the time is a topic of discussion. Some scholars and elders from recognized Indigenous communities in the region believe that calling this group "Métis" is not accurate. They argue that people of mixed heritage in the region either joined Indigenous communities or became part of European settler society. They believe there was no distinct Métis community in this region like the one led by Louis Riel in Western Canada.

The Métis Nation of Ontario's Journey

The R. v. Powley Case (2003)

The Métis Nation of Ontario was created in 1993. Its goal was to give Métis people in Ontario a political voice. This was tested in 2003 with the R. vs. Powley (2003) case. The Supreme Court of Canada made a landmark ruling. It recognized Métis people as Indigenous people with rights to hunt and fish. These rights are based on their traditional ways of life.

The court also created a way to identify Métis people, known as the "Powley test." Before this ruling, the Métis National Council (MNC), including the MNO, had already agreed on a national definition for Métis citizenship in 2002. This definition states that a Métis person identifies as Métis, has historic Métis Nation ancestry, is distinct from other Indigenous Peoples, and is accepted by the Métis Nation. The Powley ruling supported this definition.

The Powley case involved two members of the Sault Ste. Marie Métis community. They faced charges for hunting without a license. The Court clarified that Métis people are a "distinctive rights-bearing people." Their unique practices are protected by the Canadian Constitution. The Court also said that "Métis" does not include all people with mixed Indigenous and European heritage. Instead, it refers to specific peoples who developed their own customs and identity.

This was a major victory for the Powleys, the Métis Nation of Ontario, and Métis people across Canada. The Supreme Court not only cleared the Powleys but also confirmed the existence of the Sault Ste. Marie Métis community. It also set up a way to identify Métis communities in other parts of Ontario and Canada.

Current MNO Citizenship

Today, unique Métis communities continue to exist in the Upper Great Lakes region and other parts of Ontario. In 2017, the province of Ontario officially recognized six more historical Métis communities. This was after careful historical research and discussions with the Métis Nation of Ontario. These communities met the requirements set out in the 2003 Powley decision. This was in addition to the long-recognized Métis community at Sault Ste. Marie.

These historical and modern communities are connected by waterways and family ties. The Métis Nation of Ontario carefully checked old documents. They looked for Métis "root ancestors" and their families. These ancestors formed the historical Métis communities in Ontario.

Membership Discussions

In 2018, at a meeting of the Métis National Council (MNC), some concerns were raised. The MNC questioned how the MNO was defining Métis citizens. They noted that many people registered with the MNO did not meet the MNC's 2002 citizenship requirements. Specifically, they lacked a clear family link to the historic Métis homelands, especially the Red River area.

Because of this, the MNO was put on probation by the MNC for one year. This meant they had to review their citizenship list to make sure it followed the national rules. The MNO's Vice President, France Picotte, stated that the Council did not have authority over them.

The MNO did not complete the review right away. In January 2020, the MNC tried to suspend the MNO. However, this attempt failed. The MNO was readmitted to the MNC in 2021. In September 2021, the Manitoba Métis Federation left the MNC. They stated that the MNO's continued membership and the MNC's lack of action were the main reasons for their departure.

In 2023, members of the MNO voted to remove about 5,400 members from its registry. These members did not have clear connections to Métis ancestry.

How the MNO is Organized

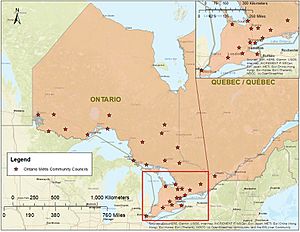

The MNO is set up like a democratically elected provincial government. Community Councils are the main link between MNO citizens and the provincial leaders. The MNO helps these Community Councils with resources and support. This ensures they can do their work well. Each Community Council also has a Youth representative. This person works with the Métis Nation of Ontario Youth Council and speaks for Métis youth in their region.

The provincial leadership is called the Provisional Council of the Métis Nation of Ontario (PCMNO). This council is responsible to MNO citizens at their Annual General Assemblies. It handles important issues and decisions that affect all Métis people in Ontario. The PCMNO has five executive members and nine councilors for different regions. It also has representatives for youth and university-age people, and four senators.

The current president is Margaret Froh. She is the first female president of the MNO. She is a lawyer and has worked in Indigenous law and policy at the MNO. Margaret Froh is a strong supporter of showing the importance of diverse representation within Indigenous communities and beyond.

Self-Government for the Métis Nation of Ontario

In February 2023, Canada and the MNO reached an important agreement. They signed a Métis Self-Government Recognition and Implementation Agreement. This agreement builds on earlier steps, including a 2019 agreement between the MNO and the Government of Canada. Formal discussions for this agreement began in 2017.

The 2019 Self-Government Agreement recognized the MNO's right to govern itself. It also set out a clear plan for the MNO's current government structures to become a federally recognized Métis Government. Canada had also promised to pass laws to make this happen.

This new legislation officially recognizes that certain Métis governments can exercise their inherent rights. These rights include the right to self-government and self-determination. This Self-Government Agreement and the new laws apply only to Métis people. They do not affect First Nations, Inuit, or any other Canadians.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |