Maria Elizabetha Jacson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Maria Elizabetha Jacson

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | 1755 |

| Died | 10 October 1829 (aged 53–54) Chelford, Cheshire, England

|

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Writer, botanist |

| Known for | Botanical writings (Linnaean) |

|

Notable work

|

Botanical Lectures By A Lady |

| Parent(s) | Rev. Simon Jacson, Anne Fitzherbert |

| Relatives | Frances Jacson (sister) |

Maria Elizabetha Jacson (born 1755 – died 10 October 1829) was an English writer from the 1700s. Her sister, Frances Jacson, was also a writer. Maria was famous for her books about botany, which is the study of plants. This was a time when it was hard for women to publish books. Sometimes, her name is spelled as Maria Jackson, Mary Jackson, or Mary Elizabeth Jackson. She lived most of her life in Cheshire and Derbyshire, England. After her father passed away, she lived with her sister.

Back then, it was common for women writers to publish their books without using their real names. Maria was inspired by Erasmus Darwin, a famous scientist. She also learned about the new way of classifying plants by Linnaeus. This system was new and a bit controversial in England. Maria wrote four books about plants using this new system.

Contents

Maria Jacson's Life Story

Maria and Frances were two of five children who grew up in the Jacson family. Their father, Reverend Simon Jacson, was a church leader in Bebington, Cheshire. Their mother was Anne Fitzherbert. The Jacson family had owned land and worked as clergy in Cheshire and Derbyshire for a long time.

In 1771, Maria's older brother, Roger, took over their father's church role. The family then moved to Stockport (1777–87) and later to Tarporley in Cheshire. Maria and Frances never married. They took care of their father after their mother died in 1795. Their father was not well and passed away in 1808.

While living in Tarporley, the family faced financial problems because of their brother Shallcross. He had large debts. To help pay these off, Maria and Frances decided to start writing books.

Moving to Somersal Hall

When their father died in 1808, the sisters needed a new home. Their cousin, Lord St Helens, offered them Somersal Hall in Derbyshire. This old house had been in their mother's family for many years. Maria and Frances could live there for the rest of their lives.

Shallcross's financial troubles came back, with even more debts. Frances used the money she earned from her books to help pay these off. Her brother Roger and Maria also helped. Shallcross died in 1821.

The Jacson children were also related to Sir Brooke Boothby. He was part of the Lichfield Botanical Society. This group connected them to new ideas in science and literature. They met famous writers like Erasmus Darwin and were part of the literary group of Anna Seward.

In 1829, Maria became very sick with a fever while visiting friends in Chelford, Cheshire. She passed away on October 10, 1829. Her sister Frances was very sad after Maria's death.

Maria Jacson's Botanical Writings

Maria Jacson showed a talent for botany from a young age. She enjoyed drawing plants, gardening, and doing plant experiments. Erasmus Darwin once praised a drawing she made of a Venus flytrap in 1788. He said she had "much botanical knowledge."

Maria Jacson was one of the first women to write about science. Her publisher included praise from Darwin and Boothby in her first book, Botanical Dialogues (1797). They said she explained a difficult science in an "easy and familiar manner." Maria was 42 when this book was published, and it was well-received. Darwin even recommended her book in his own work about educating girls.

However, Botanical Dialogues only had one edition. Perhaps it was too advanced for the young readers it was meant for.

Rewriting for a Wider Audience

Because of this, Maria rewrote the material for an older audience. This new book was called Botanical Lectures By A Lady (1804). She described it as a "complete elementary system." She hoped it would help students of any age learn this "interesting science."

Maria knew about the Lichfield Botanical Society's translation of Linnaeus' System of Vegetables (1785). She wanted her Botanical Lectures to be an introduction to this system. However, in her time, many people did not approve of female education. They especially disliked the new way Linnaeus classified plants based on how they reproduce. Maria had to be careful to balance these new ideas with what society found proper.

She wrote three books about Linnaean botany and how plants work. She also wrote a fourth book about gardening. Her book Florist's Manual was so popular that it was printed many times.

Publishing Anonymously

Since it was difficult for women to be published, Maria's books were printed anonymously, meaning "by a lady." But the introduction to Botanical Lectures was signed with her initials, M.E.J. In a later edition of Florist's Manual (1827), her full name, Maria Elizabeth Jackson, and address appeared. This might have been added by the publisher, as it had some errors. The first edition of that book simply ended with "M.E.J., Somersal Hall."

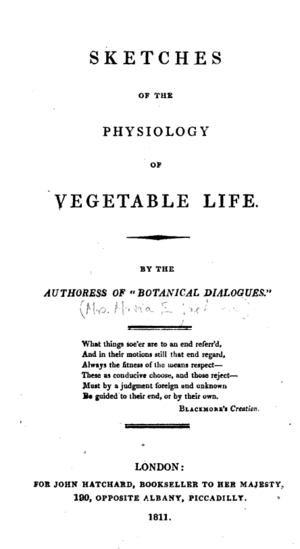

Her early writings were greatly influenced by Darwin. However, her book Sketches of the Physiology of Vegetable Life (1811) showed her own independent ideas. She even drew the pictures for this book herself.

Maria understood the challenges women writers faced. In her first book, she wrote about how women had to be careful about showing their knowledge. She described these rules as coming from the "world" around her, not from herself. She advised her readers about the risks of being known for what they knew.

Botanical Dialogues (1797)

Botanical Dialogues Between Hortensia and her Four Children, Charles, Harriet, Juliette and Henry Designed For the Use in Schools (1797) was written as conversations. It features a mother, Hortensia, talking with her four children. The book mentions Darwin's poetic descriptions of plants from his book The Botanic Garden.

Maria used the differences in how plants reproduce to talk about the different roles boys and girls were expected to have in society. While she explained these social rules, she also showed that she didn't fully agree with them.

Works

- Botanical Dialogues 1797

- Botanical Lectures By A Lady 1804 (a revised version of Dialogues for a wider audience)

- Sketches of the Physiology of Vegetable Life 1811

- A Florist's Manual 1816

See also

In Spanish: Maria Elizabetha Jacson para niños

In Spanish: Maria Elizabetha Jacson para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |