Matchstick banksia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Matchstick banksia |

|

|---|---|

|

|

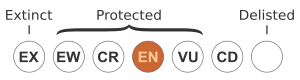

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Banksia |

| Subgenus: | Banksia subg. Isostylis |

| Species: |

B. cuneata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Banksia cuneata A.S.George

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Banksia cuneata, also known as the matchstick banksia or Quairading banksia, is a special type of flowering plant. It belongs to the Proteaceae family. This plant is an endangered species, meaning it's at risk of disappearing forever.

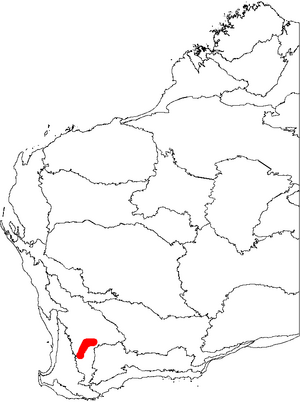

You can only find the matchstick banksia in the southwest part of Western Australia. It's part of a small group of three Banksia species called Banksia subg. Isostylis. These plants have unique flower clusters that look like dome-shaped heads, not the usual spiky banksia flowers.

The plant can grow as a shrub or a small tree, up to 5 meters (16 feet) tall. It has prickly leaves and flowers that are pink and cream. People call it the "Matchstick Banksia" because its flower buds look like tiny matchsticks before they open. honeyeater birds help to pollinate its flowers.

Even though people collected B. cuneata before 1880, it wasn't officially named until 1981 by an Australian botanist named Alex George. There are two main groups of these plants that are genetically different. This banksia is endangered because most of its natural home has been cleared for farms.

Matchstick banksias are killed by fire, but they grow back from seeds. This means they are very sensitive to how often bushfires happen. If fires happen too often (like every four years), the young plants won't have enough time to grow up and make seeds, which could wipe out the whole group. This plant is rarely grown in gardens, and its prickly leaves make it hard to use for cut flowers.

Contents

What the Matchstick Banksia Looks Like

The Banksia cuneata grows as a shrub or a small tree. It can reach up to 5 meters (16 feet) high. It doesn't have a special woody base called a lignotuber that helps some plants regrow after fire. It usually has one or more main stems with smooth grey bark and many branches. Young stems are hairy, but they become smooth as they get older.

The leaves are shaped like a wedge, with jagged edges that have one to five teeth on each side. They are about 1 to 4 centimeters (0.4 to 1.6 inches) long and 0.5 to 1.5 centimeters (0.2 to 0.6 inches) wide. They grow on a small stalk about 2 to 3 millimeters long. The top of the leaf is a dull green. Like the stems, young leaves are hairy, but they soon lose their hairs.

The flowers grow in dome-shaped clusters at the ends of branches. These clusters are about 3 to 4 centimeters (1.2 to 1.6 inches) across. Each cluster has about 55 to 65 individual flowers. Small leaf-like parts called bracts surround the base of the flower cluster.

Each flower has four parts joined together, called a perianth, and a single pistil. The style (the top part of the pistil) is first hidden inside the flower, but it breaks free when the flower opens. In B. cuneata, the perianth is about 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) long. Before the flower opens, the long, thin perianth with its tip looks like a matchstick, which is how the plant got its common name.

At first, the perianth is mostly cream-colored, with a pink base. Later, it turns completely pink. The style is cream at first but then turns red. The part that holds the pollen is green.

After the flowers fade, they fall off the flower heads, leaving a woody base. This base can hold up to five seed pods, called follicles. These pods are grey with mottled spots, smooth, and covered in fine hairs. They are about 1 to 1.3 centimeters (0.4 to 0.5 inches) high. Each pod holds up to two seeds. The seeds are roughly triangular with a large papery wing.

You can tell Banksia cuneata apart from other similar banksias by its brighter flowers and duller leaves. It's also smaller than the Holly-leaved banksia and has smooth bark, smaller leaves, flowers, and fruit. The Wagin banksia has even smaller leaves, flowers, and fruit, and its leaves are not as prickly as those of B. cuneata.

Discovery and Naming

The first known sample of B. cuneata was collected by Julia Wells before 1880. The official sample used to describe the species was collected by botanist Alex George on November 20, 1971. He found it at Badjaling Nature Reserve, near Quairading, in Western Australia.

Alex George officially described and named the species almost ten years later, in 1981. The name cuneata comes from a Latin word meaning "wedge-shaped," which describes the shape of its leaves.

This species has always been known by the same name. It doesn't have any other scientific names or different types (subspecies or varieties) that have been officially recognized. Its common names are Matchstick Banksia or Quairading Banksia.

Where the Matchstick Banksia Lives

The B. cuneata is an endangered species. It only grows in a small area, about 90 kilometers (56 miles) wide, around the towns of Pingelly and Quairading in Western Australia.

It prefers to grow in deep yellow sand, on land that is between 230 and 300 meters (750 and 980 feet) high. It often lives in woodland areas alongside other plants like the Acorn banksia and Xylomelum angustifolium.

The number of B. cuneata plants and where they live has changed over time. In 1982, a survey found about 450 plants in five groups. The largest group had 300 plants. However, in 1988, only four groups with 300 plants were found in total. Since then, reports have varied, with between 6 and 11 groups and a total of 340 to 580 plants.

Life Cycle and Ecology

Matchstick banksia flowers bloom from September to December. honeyeater birds are the main pollinators. Features like bright red or pink flowers, a straight style, and a tube-shaped perianth are thought to attract birds.

The way the B. cuneata flower is built, with the style tip acting as a pollen presenter, suggests that it might often fertilize itself. However, the plant has a clever trick: the pollen is released before the pistil is ready to receive it. This helps prevent individual flowers from self-fertilizing. But because flowers are clustered together, it's common for different flowers on the same plant to fertilize each other.

Studies show that how much the plants cross-pollinate (mate with different plants) changes between groups. Plants in healthy bushland areas tend to cross-pollinate more. But those in disturbed areas are more likely to self-pollinate. This might be because disturbed areas have more plants close together, or because they don't have enough birds to help with pollination.

If pollinators are kept away, no seeds are produced, showing that the plant needs pollinators to make seeds. About 96% of fertilized pods mature, and about 82% of seeds become viable (able to grow). These are very high numbers for a Banksia, meaning the plant has no trouble getting enough nutrients.

This species produces many old flower heads (cones), often more than 500 per plant. But each cone usually has only one seed pod. So, the total number of seed pods per plant is about average for a Banksia.

Banksia cuneata plants are killed by bushfires because they don't have a lignotuber. However, they are strongly serotinous. This means their seeds are only released after a fire. The plant stores seeds in its canopy between fires. The heat from a bushfire melts a resin that seals the seed pods, causing them to open and release the seeds. This helps the population grow back after a fire.

Young B. cuneata plants need about four years to mature. If a fire happens during this time, the entire group of plants could be wiped out because there won't be any seeds to regrow. Studies suggest that the best time between fires for the most plants to grow is about 15 years. More frequent fires kill adult plants before they can make enough seeds. Less frequent fires mean fewer chances for seeds to spread and sprout.

It's unusual, but B. cuneata doesn't seem to lose many seeds to animals eating them. In most other species, insect larvae eat many seeds, and birds break open cones looking for these larvae. It seems no insect species has adapted to eat B. cuneata seeds. This might be because there are very few seeds per cone, and the species is rare.

As a result, this plant has a very high rate of viable seeds. In one study, 74% of all seeds produced over 12 years were viable. Seeds less than 9 years old were about 90% viable. After nine years, seeds quickly lose their ability to grow as the pods decay.

Plants start producing seeds slowly. Plants between 5 and 12 years old store about 18 seeds in their canopy. But this number grows very quickly. 25-year-old plants can have tens of thousands of seeds. As plants get older, the weight of the cones can cause major branches to break off. By age thirty, plants often have broken branches, which can lead to their death. Most plants probably don't live longer than 45 years.

Even with many viable seeds, very few seedlings survive. This is mainly due to a lack of water. In one study, after a controlled fire, about 17,100 viable seeds were released. Less than 5% of them sprouted, and only eleven plants survived the first summer drought. The plants that survived were in places where they got more water, like along road shoulders where they benefited from water runoff. This shows that water is the most important factor for seedling survival.

Conservation Efforts

Banksia cuneata was once considered critically endangered after a 1982 survey found only five groups with about 450 plants. The largest group was in a protected area, but others were along roadsides. Since then, more plants have been found, and the number of plants has slowly increased thanks to conservation efforts like fencing and controlling rabbits. Because of this small recovery, it is now considered endangered, but no longer critically endangered.

In 1987, the Department of Environment and Conservation in Western Australia burned part of one group of plants to see if it would help them regrow. The adult plants died, and the new seedlings did not survive the summer drought. In 1995, a "Matchstick Banksia Recovery Team" was formed. They successfully helped many seedlings grow. A large group of adult plants was destroyed by a bushfire in 1996, which was worrying, but then many new seedlings grew.

Threats to B. cuneata include land clearing, which destroys plants and breaks up their living areas. Other threats are animals eating the plants, competition from weeds, changes in how often fires happen, and increasing saltiness in the soil. A survey called The Banksia Atlas found one group of plants on the side of a road that were getting old with no new seedlings, and the area was full of weeds.

Many of the remaining plants are on private land. Protecting them depends on good relationships with landowners. Many have helped by fencing off areas and keeping rabbits away. There have also been attempts to move plants to safer areas, which have been somewhat successful, especially when the plants were watered during their first year.

Land Clearing Impact

Even before much of the Wheatbelt was cleared for farming in the 1930s, B. cuneata likely lived in scattered areas. This is because the deep yellow sand it prefers only makes up 10 to 15% of the region. Now, about 93% of the land has been cleared. This means land clearing has further broken up the plant's habitat and greatly reduced the number of individual plants.

Protecting Genetic Diversity

The different groups of B. cuneata plants have a surprisingly high amount of genetic diversity for a rare species. However, they fall into two distinct genetic groups. These groups are separated by the Salt River, a river system that is sometimes dry and salty. This river creates an environment that is not good for B. cuneata or the birds that pollinate it.

Because of this, the river acts as a barrier, preventing the exchange of genetic material between the groups. This allows the groups on different sides of the river to become genetically different. For conservation, this means efforts should be made on both sides of the river to protect as much genetic diversity as possible. It was suggested that protecting one large group from each side would be enough. However, more recent studies show that the number of plants needed to reduce the risk of extinction is more than ten times the current number. This means all groups and all available habitat should be protected.

Disease Threat

A plant disease called Phytophthora cinnamomi dieback has not been a major threat to B. cuneata so far. However, tests show that this plant is very vulnerable to it. In one study, B. cuneata was the most susceptible of 49 Banksia species tested. 80% of the plants died within 96 days of being exposed to the disease, and 100% died within a year.

Climate Change Impact

The survival of B. cuneata is closely linked to rainfall because its seedlings are very sensitive to drought. This makes it especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change. As early as 1992, it was noted that winter rainfall in the Quairading region was decreasing by about 4% every ten years. If this trend continues, it could reduce where the species can live.

More recently, a detailed study on climate change's impact found that severe climate change would likely lead to the plant's extinction. Even mild climate change could reduce its living area by 80% by 2080. However, if the species can move into new suitable areas, there might not be any reduction in its range under moderate climate change.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Banksia cuneata para niños

In Spanish: Banksia cuneata para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |