Metanephrops challengeri facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Metanephrops challengeri |

|

|---|---|

|

|

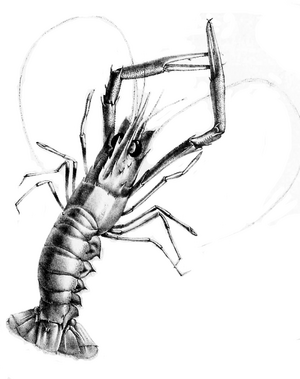

| Illustration by C. Spence Bate (1888) | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Nephrops challengeri Balss, 1914 |

The Metanephrops challengeri is a type of slim, pink lobster. It is also known as the New Zealand lobster or New Zealand scampi. This lobster lives around the coast of New Zealand.

It is usually about 13 to 18 centimeters (5 to 7 inches) long. It weighs around 100 grams (3.5 ounces). Its body and tail are smooth. Adult scampi are white with pink and brown marks. They have two long, thin claws that are easy to see.

M. challengeri lives in burrows deep in the ocean. They can be found at depths of 140 to 640 meters (460 to 2,100 feet). They live in different types of soft sand or mud. These lobsters can live for up to 15 years. However, females lay only a small number of eggs. The young larvae hatch at an advanced stage.

This lobster is an important food source for fish like ling. It is also a popular seafood for people. Fishing boats catch about 1,000 tonnes (2.2 million pounds) each year. This is done under New Zealand's Quota Management System. This system helps control how much scampi can be caught.

Scientists first found this species during the Challenger expedition (1872–1876). But it was not described as a separate species until 1914. This was done by Heinrich Balss. It was first placed in the Nephrops group. In 1972, it was moved to a new group called Metanephrops. Most other lobsters from the Nephrops group were also moved.

Contents

What Does the New Zealand Scampi Look Like?

The Metanephrops challengeri is a thin lobster. It is usually 13 to 18 centimeters (5 to 7 inches) long. Some can grow up to 25 centimeters (10 inches). They can weigh up to 100 grams (3.5 ounces).

Its main claws are long and narrow. They are also slightly different in size. The second and third pairs of legs also have small claws. But the fourth and fifth pairs do not. The top shell, called the carapace, is smooth. It has a long, narrow point at the front called a rostrum. This point is almost as long as the carapace itself.

Adult scampi are mostly white. But the front of the rostrum and the sides of the tail are pink. Bright red bands cross the base of the rostrum. They also appear on the back edge of the carapace and on the claws. Each part of the tail also has red bands. The top parts of the tail are brown. There are also two brown spots on the top of the carapace.

Scientists believe M. challengeri has a very old body shape. It has fewer new features than even the oldest known fossil lobsters. Its rostrum is longer than other lobsters in its group. The ridge along the middle of its carapace has only two small spines. Unlike some other lobsters, its carapace is smooth. Its tail segments are also smooth. The claws are covered in tiny bumps.

Life Cycle of the New Zealand Scampi

Metanephrops challengeri becomes old enough to have babies at 3 to 4 years of age. It can live for up to 15 years.

Female scampi lay a small number of very large eggs. These eggs are usually about 2.5 millimeters (0.1 inches) wide. They are blue in color. The baby lobsters, called larvae, hatch at a special stage called zoea. These zoea larvae are 10.0 to 11.5 millimeters (0.4 to 0.45 inches) long. They have all the legs and parts of their head and chest. They use these legs to swim. But they do not have the swimming parts on their tail yet.

This larval stage lasts less than four days. After this, the young lobsters molt. They change into a post-larval stage. The post-larva swims using its tail parts. Later, the post-larva molts again and becomes an adult. Scientists rarely see larvae in the wild. This shows that they quickly change into the adult form that lives on the ocean floor.

Where New Zealand Scampi Live and What Eats Them

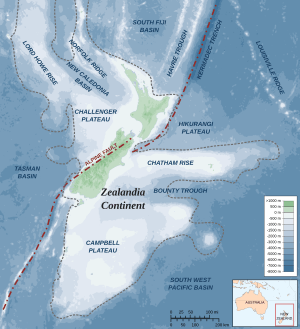

Metanephrops challengeri lives around the coasts of New Zealand. This includes the Chatham Islands. They live at depths of 140 to 640 meters (460 to 2,100 feet).

They make burrows in suitable soft sediments. These lobsters are an important food source for fish like ling (Genypterus blacodes). Lobsters do not have many parasites. The most important one for M. challengeri is a tiny organism called Myospora metanephrops. This parasite can damage the muscles of infected lobsters. But scientists are still studying how much it affects the animals and the fishing industry. When it was found in 2010, M. metanephrops was the first parasite of its kind found in a true lobster.

Fishing for New Zealand Scampi

People have been fishing for Metanephrops challengeri to sell since the 1980s. Between 1988 and 1991, the amount of scampi caught in New Zealand grew a lot. It went from 55,000 kilograms (121,000 pounds) to about 500,000 kilograms (1.1 million pounds).

Rules about how much could be caught started in 1990–1991. Now, about 1,000,000 kilograms (2.2 million pounds) are caught each year. This is done by trawlers. The main fishing areas are four parts of the continental shelf around New Zealand. These include the Campbell Plateau, Chatham Rise, the Wairarapa coast, and the Bay of Plenty.

Most of the fishing vessels used are 20 to 40 meters (66 to 131 feet) long. They use special nets that are low to the ground. The amount of scampi caught can change a lot. This depends on the depth, the area, and the year. M. challengeri is seen as a special food. Most of what is caught is sent to other countries. So, it is not often seen in restaurants in New Zealand.

In 2003, there was an inquiry in the New Zealand Parliament. This was about how fishing permits were given out for scampi. Some people thought there might have been unfair treatment. The inquiry found that a large fishing company had received special treatment. Because of this, the government added M. challengeri to their Quota Management System. This system helps manage fishing to keep it fair and sustainable. They also paid money to some fishermen who had been treated unfairly. Under this system, a total limit of 1,291,000 kilograms (2.8 million pounds) was set for M. challengeri in 2011.

Protecting the New Zealand Scampi

The Metanephrops challengeri is currently listed as "Least Concern" on the IUCN Red List. This means it is not in immediate danger of disappearing. This is partly because of the Quota Management System.

However, the number of these lobsters seems to be going down. This is based on counts of their burrows and how much is caught. Estimates of the total population size vary. Some methods, like counting burrows, suggest there could be as many as 28 million lobsters. In this case, the yearly catch would be only 2%–4% of the total population.

Other methods, based on lobsters seen during surveys, suggest there might be only 2–11 million lobsters available to fishing boats. If this is true, the yearly catch could remove 12%–28% of that population. Sometimes, other animals are caught by accident during scampi fishing. This is called bycatch. The New Zealand sea lion is one such animal. It is considered a vulnerable species by the IUCN.

How Scientists Classify New Zealand Scampi

Metanephrops challengeri was first described by Heinrich Balss in 1914. He named it Nephrops challengeri. Two lobsters were found during the Challenger expedition. They were collected from the ocean floor in the Tasman Sea.

These lobsters were included in a report by Charles Spence Bate. But he did not separate them from another species, Nephrops thomsoni. Balss realized that Spence Bate's N. thomsoni was actually two different species. He kept the name M. thomsoni for the lobsters from the Philippines. He then created a new species for the lobsters from New Zealand. Balss chose the two lobsters seen by Spence Bate as the main examples for his new species, Nephrops challengeri. Both were females. They are now kept at the Natural History Museum, London.

In 1972, a scientist named Richard Jenkins moved this species to a new group called Metanephrops. He moved almost all other species that were then in the Nephrops group. Only the main species of Nephrops, Nephrops norvegicus, stayed in that group.

Jenkins placed M. challengeri in the "thomsoni group" within Metanephrops. This group also included M. thomsoni and other similar species. Jenkins thought this group of species came from northern Australia or Indonesia. He believed M. challengeri reached New Zealand later. More recent studies of DNA suggest that M. challengeri is a very old type of lobster in its group. It might be linked to M. neptunus. Scientists now think the Metanephrops group might have started in the South Atlantic.

See also

In Spanish: Langosta de Nueva Zelanda para niños

In Spanish: Langosta de Nueva Zelanda para niños

Images for kids

-

Illustration by C. Spence Bate (1888)