Continental shelf facts for kids

A continental shelf is a part of a continent that is covered by a relatively shallow ocean. This shallow water area is called a shelf sea. Many of these shelves were dry land during past ice ages when sea levels were much lower. If a shelf surrounds an island, it's called an insular shelf.

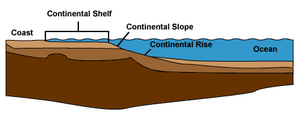

The edge of the continent, called the continental margin, connects the continental shelf to the deep abyssal plain. This margin includes a steep continental slope and a flatter continental rise. The continental rise is where sediment from the continent slides down the slope and piles up. It can stretch as far as 500 km (310 mi) from the slope.

Under international law, the term continental shelf also has a special meaning. It refers to the part of the seabed next to a country's coast that belongs to that country.

Contents

What Does a Continental Shelf Look Like?

The continental shelf usually ends where the ocean floor suddenly gets much steeper. This steep drop-off is called the shelf break. Below the shelf break is the continental slope. Even further down is the continental rise, which eventually blends into the very deep ocean floor, known as the abyssal plain. Both the continental shelf and the slope are parts of the continental margin.

The shelf area is often divided into three parts: the inner continental shelf, mid continental shelf, and outer continental shelf. Each part has its own unique shape and types of sea life.

The shelf break is usually found at a depth of about 140 m (460 ft). This consistent depth likely shows us where the sea level was during past ice ages.

The continental slope is much steeper than the shelf. Its average angle is 3 degrees, but it can be as gentle as 1 degree or as steep as 10 degrees. The slope often has deep cuts called submarine canyons.

Where Are Continental Shelves Found?

Continental shelves cover about 27 million square kilometers (10 million sq mi). This is about 7% of the total ocean surface. The width of a continental shelf can vary a lot. Some areas have almost no shelf at all. This often happens where an oceanic plate is diving under a continental crust, like off the coast of Chile.

The largest shelf is the Siberian Shelf in the Arctic Ocean, which is 1,500 km (930 mi) wide. The South China Sea sits on another huge shelf called the Sunda Shelf. This shelf connects Borneo, Sumatra, and Java to the Asian mainland. Other well-known areas with shelves include the North Sea and the Persian Gulf.

On average, continental shelves are about 80 km (50 mi) wide. The water depth on the shelf is usually less than 100 m (330 ft). The slope of the shelf is very gentle, usually around 0.5 degrees. The height differences on the shelf are also small, less than 20 m (66 ft).

Even though the continental shelf is part of the ocean, it's actually the flooded edge of a continent, not part of the deep ocean basin.

- Passive continental margins, like most of the Atlantic Ocean coasts, have wide and shallow shelves. These shelves are made of thick layers of terrigenous sediment that have eroded from the nearby continent over a long time.

- Active continental margins have narrow, steeper shelves. This is because frequent earthquakes move sediment quickly into the deep sea.

| Ocean | Active Margin | Passive Margin | Total Margin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Biggest | Average | Biggest | Average | Biggest | |

| Arctic Ocean | 0 | 0 | 104.1 ± 1.7 | 389 | 104.1 ± 1.7 | 389 |

| Indian Ocean | 19 ± 0.61 | 175 | 47.6 ± 0.8 | 238 | 37 ± 0.58 | 238 |

| Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea | 11 ± 0.29 | 79 | 38.7 ± 1.5 | 166 | 17 ± 0.44 | 166 |

| North Atlantic Ocean | 28 ± 1.08 | 259 | 115.7 ± 1.6 | 434 | 85 ± 1.14 | 434 |

| North Pacific Ocean | 39 ± 0.71 | 412 | 34.9 ± 1.2 | 114 | 39 ± 0.68 | 412 |

| South Atlantic Ocean | 24 ± 2.6 | 55 | 123.0 ± 2.5 | 453 | 104 ± 2.4 | 453 |

| South Pacific Ocean | 214 ± 2.86 | 357 | 96.1 ± 2.0 | 778 | 110 ± 1.92 | 778 |

| All Oceans | 31 ± 0.4 | 412 | 88.2 ± 0.7 | 778 | 57 ± 0.41 | 778 |

Sediments on the Shelf

Continental shelves are covered by sediments that come from the land. These are called terrigenous sediments. However, most of the sediment on shelves today isn't from rivers flowing now. About 60–70% of it is relict sediment. This means it was deposited during the last ice age, when sea levels were 100–120 m (330–390 ft) lower than they are today.

Sediments usually get finer the further they are from the coast. Sand is found in shallow waters where waves stir things up. Silt and clay are found in calmer, deeper waters further offshore. These sediments build up 15–40 cm (5.9–15.7 in) every thousand years. This is much faster than the sediments found in the deep sea.

Shelf Seas: The Waters Above the Shelf

"Shelf seas" are the ocean waters that sit on top of the continental shelf. Their movement is affected by tides, wind, and fresh water from rivers. These areas are often full of life because the shallower waters mix easily. This mixing brings up nutrients, which helps many sea creatures grow. Even though shelf seas only cover about 8% of the Earth's ocean surface, they produce 15–20% of the ocean's total plant life.

In shelf seas in temperate (mild climate) areas, there are three main types of water conditions:

- In shallower water with stronger tides, the water stays well mixed all year round. The tides are strong enough to overcome the warming of the surface water.

- In deeper water, the surface warms up in summer, creating layers. A warm layer sits on top of cooler, deeper water.

- Near estuaries (where rivers meet the sea), like in the Irish Sea or North Sea, the water layers can change quickly. This is due to the fresh river water mixing with the salty ocean water.

Scientists are studying how changing winds, rainfall, and ocean currents are affecting shelf seas as the ocean warms.

Life on the Continental Shelf

Continental shelves are full of life because sunlight can reach the shallow waters. This is very different from the deep ocean floor, which is like a desert for living things. The water above the continental shelf is called the neritic zone. The seafloor of the shelf is called the sublittoral zone. Less than 10% of the ocean is made up of shelves. Only about 30% of the continental shelf seafloor gets enough sunlight for plants to grow.

Even though shelves are usually very fertile, if there isn't enough oxygen during the time sediments are forming, these deposits can become sources for fossil fuels over a very long time.

Why Are Continental Shelves Important?

The continental shelf is the part of the ocean floor we know best because it's easier to reach. Most commercial activities in the sea happen on the continental shelf. This includes getting hydrocarbons (like oil and gas) and different types of ores from the seabed.

Countries have claimed rights over their continental shelves for a long time. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1982 set new rules. It created a 200 nmi (370 km; 230 mi) exclusive economic zone for countries. It also gave countries rights to their continental shelves if they extend beyond that distance, up to 350 nmi (650 km; 400 mi) from their coast.

It's important to remember that the legal definition of a continental shelf is different from the geological one. For example, islands like the Canary Islands don't have a true geological continental shelf, but they have a legal one under UNCLOS.

See also

In Spanish: Plataforma continental para niños

In Spanish: Plataforma continental para niños

- Continental island

- Exclusive economic zone

- International waters

- Land bridge

- Outer Continental Shelf

- Territorial waters

Images for kids

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |