Military Station archaeological site facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Military Station archaeological site |

|

|---|---|

Site of building platforms

|

|

| Location | 200 Jenolan Caves Road, Hartley, City of Lithgow, New South Wales, Australia |

| Built | 1815–1832 |

| Official name: Military Station Archaeological Site and Burial at Glenroy; Cox's River Military Station; Government Provision Depot | |

| Type | State heritage (archaeological-terrestrial) |

| Designated | 1 October 2010 |

| Reference no. | 1840 |

| Type | Other - Government & Administration |

| Category | Government and Administration |

| Builders | Convict labour |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

The Military Station archaeological site is a special historical place in Hartley, Australia. It was once a stock station, a military base, and a place to store supplies. Today, it is an archaeological site, meaning scientists study its remains to learn about the past.

This site was built between 1815 and 1832. Much of the work was done by convict labour, people sent to Australia as punishment. The site is also known by other names like Military Station Archaeological Site and Burial at Glenroy. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 1 October 2010 because of its important history.

Contents

History of the Site

Early Days: Aboriginal Land

The land where the military station stands, called Glenroy, belongs to the Wiradjuri people. Their traditional lands are around the Lachlan, Macquarie, and Murrumbidgee rivers. The Wiradjuri name means "people of the three rivers." These rivers were their main food source.

The Hartley area is where mountains meet plains. It was a border between the Wiradjuri and Gundungurra Aboriginal groups. Aboriginal people often moved between the cold highlands and warmer plains. They followed old routes through the land.

Before settlers arrived, the Lett Valley offered many native foods and medicinal plants. Aboriginal people used traps to catch fish and eels. They also used controlled fires to keep the bushland open. This helped new plants grow and attracted animals for hunting.

Governor Macquarie's Vision

Lachlan Macquarie became the Governor of New South Wales in 1810. He focused on building public works using convict labour. He wanted to make the colony stronger. Macquarie also encouraged exploration. By the time he left, the explored area was much larger.

In 1813, explorers Blaxland, William Wentworth, and Lawson crossed the Blue Mountains. This was exciting news for Governor Macquarie. He saw it as a chance for the colony to grow. He sent Surveyor George Evans to explore further. Evans found new plains, including the Bathurst Plains.

Macquarie decided to build a road to this new country. He asked William Cox to build it. This road would help claim the land west of the mountains. It would also allow starving livestock to reach new pastures.

Building Cox's Road

William Cox's road reached the Lett and Cox's River junction in December 1814. Two bridges were built to cross the rivers. The bridge over the River Lett was small and built quickly. The Cox's River bridge was larger and took seven days to finish.

In April 1815, Governor Macquarie and his group traveled on the new road. They admired the mountain pass and the beautiful Vale of Clwydd. They reached Cox's River and camped there. On Sunday, April 30, 1815, the first Anglican church service west of the Blue Mountains was held at this camp. The group then continued to Bathurst, proclaiming it a town on May 7, 1815.

The Government Provision Depot

In 1815, a cattle herd was moved to a station near the Vale of Clywdd. William Hassall found many cattle had died. So, he moved the herd to a better spot, "a very pleasant hill opposite the bridge." This was where the Governor had camped.

By March 1816, men had built a large stockyard and three huts. One hut was for stockmen, one for storage, and another for soldiers and the overseer. These huts were made of split logs and bark.

In 1816, a group of Aboriginal people from east of the Blue Mountains raided the site. They drove away the stockmen. Governor Macquarie sent soldiers from the 46th Regiment to protect the depot. They were told to keep Aboriginal people away. This marked the start of military protection at Glenroy.

This raid was one of only a few recorded conflicts west of the Blue Mountains between 1815 and 1822. After 1821, more settlers moved west, and tensions grew. Governor Brisbane declared martial law in 1824 to try and restore peace.

A Stopping Point for Travellers

The government depot became a popular stopping point for travellers. It had military protection, good grass, and water. Explorers like John Oxley and botanist Allan Cunningham camped there in 1817 and 1822. Cunningham even discovered new plants nearby.

In 1820, Corporal James Morland said that all men returning from Bathurst got supplies at the depot. He also said the huts needed constant repair. Governor Macquarie visited again in 1821.

In 1824, French explorers Dumont D'Urville and Rene-Primevre Lesson found the site beautiful. At that time, six soldiers and a corporal were stationed there.

The military presence grew in the mid-1820s. A new log hut was built for an officer in 1826. By 1827, a non-commissioned officer and 10-12 men were at the station. Some travellers found it annoying that soldiers relaxed while they struggled through nearby river crossings.

Repairs were made in 1827 and 1828. In 1829, Jane, the wife of Lieutenant Kirkley, died at the station. Road gangs were nearby in 1830. In 1831, the officers' house needed repairs because of bugs. A single headstone from this time belongs to Eliza Rodd, the child of a soldier.

Abandonment and Later Years

The western road was rerouted in 1831-32. This meant the military station was no longer needed. It was abandoned and sold in 1837 to James Blackett. A plan from that time shows four buildings and a paddock. The name Glenroy likely started being used around 1837.

By 1914, the site was in ruins. The garden was overgrown, fences were rotted, and buildings were just piles of timber. Only a lone chimney remained. However, some huts might have been rebuilt and used later. In 1936, a monument was put up nearby to remember the Anglican service from 1815. The site has remained in private hands for over 50 years.

Eliza Rodd's Grave

Eliza Rodd was the daughter of James Rodd, a soldier. He fought in the Anglo-American war and was in France before the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. He married Judith Joseph Baudelet in France.

His regiment moved to Ireland, then to New South Wales in 1826. James and Judith brought their son to Australia. But they left their four-year-old daughter, Marie-Anne, with her grandparents in France.

James Rodd was first stationed at Parramatta. He became a colour sergeant in 1827 and was sent to Bathurst. By 1829, he was in charge of soldiers at Glenroy. Eliza Rodd was born on January 10, 1831, in New South Wales. She died on September 14, 1831.

James Rodd and his family moved back to Sydney in early 1832. Eliza's grave was left alone on a hillside. Judith died in Sydney in April 1832. The 39th Regiment then moved to India. Colour Sergeant James Rodd died in India in December 1832. This left his two young sons, Ambroise and James Jr., as orphans.

Since 2007, efforts have been made to restore and protect Eliza Rodd's grave. Repairs were finished in mid-2009. An old photo from the early 1900s shows a wooden fence around the grave.

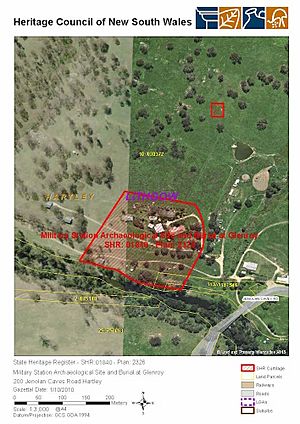

What the Site Looks Like Today

The archaeological site is on a property called Glenroy, on the road to the Jenolan Caves. It is mostly open and grassy, with some trees on small hills. The Cox's River runs at the bottom of the property. You can still see signs of old river crossings, like timber posts.

Eliza Rodd's grave is near the middle of the property. It has a sandstone headstone and footstone. A modern steel fence, about 130 cm high, surrounds it.

You can also see remains of old building platforms. These are flat grassy areas that don't match the natural slope of the land. They are where the old buildings were, as shown on a map from 1837. Along the driveway, you might find small pieces of old china, pottery, and glass. Some of these pieces are from the early to mid-19th century. People who live there say these pieces keep appearing over time.

Condition of the Site

As of 2010, much of the historical evidence is still covered and hidden. The sites of the four early wooden buildings are on a terraced hill above Cox's River. The old Cox's Road is visible further east, but not at Glenroy itself.

Allowing people to picnic without rules could harm the archaeological site. A newer brick house, built around the 1970s, is very close to where the old military station buildings were.

Changes Over Time

- 1816: The first three huts and a yard were finished.

- 1820s: A new log hut was added.

- 1827-28: Some repairs were made.

- 1831: Repairs were done to the officers' house.

- 1914: Most of the site had disappeared.

- Late 20th century: Evidence suggests new buildings were put on the old platforms, but they have also disappeared.

- 1970s: A large brick house was built close to the military station site.

- 2009: Eliza Rodd's grave was restored and a temporary metal fence was put up to protect it.

Why This Site is Important

The military station and burial site are very important to the history of New South Wales. They show how Europeans first moved into and claimed land west of the Blue Mountains. This expansion eventually led to the displacement of local Aboriginal people. The 1816 raid by Aboriginal people on the depot was possibly the first major conflict between Europeans and Aboriginal people west of the Blue Mountains after Cox's Pass opened.

The site also shows early government rules to control settlement. It is important for the Anglican religion because the first church service west of the mountains happened here. For Europeans, it was the first government supply depot and military base west of the Blue Mountains.

The Military Station archaeological site was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on October 1, 2010, because it meets several important criteria:

- It shows the pattern of history in New South Wales.

The Glenroy site was the first military station west of the Blue Mountains. It was also where the first Anglican church service took place. It was a main stopping point for all travellers crossing Cox's Pass, including Governor Macquarie in 1815.

This site is also important as one of the earliest recorded conflicts between Europeans and Aboriginal people west of the Blue Mountains. It was one of only four such incidents between 1815 and 1822, a time that was mostly peaceful before more settlers arrived.

- It is linked to important people or groups in New South Wales history.

The site is important because Governor Macquarie and his group stopped here on their first trip west of the Blue Mountains. It is also linked to the 46th and 39th regiments of soldiers who were stationed there. Many explorers and scientists, like Allan Cunningham and the French explorers Dumont D'Urville and Rene-Primevre Lesson, camped here. They were inspired by its beauty and unique plants.

- It shows important artistic or technical achievements.

The site and its surroundings were so beautiful that explorers and travellers wrote about them in detail. It was a landmark, marking the end of the fertile Vale of Clwydd after descending Cox's Pass. The location of the military station helped control livestock and prevent uncontrolled settlement. It also helped keep an eye on the local Aboriginal presence and ensure communication between Bathurst and the coast.

- It has a strong link to a community or cultural group for social, cultural, or spiritual reasons.

The site is important to the Anglican and Christian community. It shows how the religion spread west of the Blue Mountains. It also highlights the importance of religious practice in the early 19th century, even in remote areas.

- It can provide information about the history of New South Wales.

The site can show us how early military and government supply stations were set up west of the Blue Mountains. It can provide archaeological evidence about the people who lived there. This can help us compare these isolated depots with those closer to established towns. We might also learn about the differences between a military station and a convict stockade. Pottery, glass, and china pieces can show what goods were available to the people stationed there.

- It has rare or unique aspects of New South Wales history.

This location is rare because it was the site of the first Anglican church service west of the Blue Mountains. It is also one of the earliest recorded Aboriginal/European conflicts west of the Blue Mountains after Cox's Road opened.

- It shows the main features of cultural or natural places in New South Wales.

The site is important as one of the earliest places where Europeans lived west of the Blue Mountains.

Images for kids