Mission blue butterfly habitat conservation facts for kids

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) works hard to protect the homes of the Mission blue butterfly. This butterfly is an endangered species, which means it's at risk of disappearing forever. The USFWS created a plan in 1984 to save the butterfly's habitat. This plan focuses on protecting areas where the butterflies live and fixing places damaged by cities, off-road vehicles, and plants that don't belong there. One great example of this work is happening at the Marin Headlands, which is part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Even wildfires, which can be damaging, sometimes create new chances to help the butterflies.

Contents

Protecting Mission Blue Homes: Marin Headlands

The Marin Headlands has a special program to protect the Mission blue butterfly. This area used to be owned by the United States Army. For many years, the Army built forts and missile sites there. While they were there, the Army planted many trees that were not native to the area.

Today, these non-native trees have grown a lot and are taking over the butterfly's natural home. The protection program aims to remove these unwanted plants from certain areas. Some of these plants include blue gum eucalyptus, Monterey cypress, Monterey pine, and blackwood acacia. The Mission Blue Butterfly UserFee Project is working to get rid of these plants and replace them with native coastal prairie plants. This helps the butterflies find the plants they need to survive.

Saving Habitat on San Bruno Mountain

Another big effort to save the Mission blue butterfly is happening at San Bruno Mountain. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has protected over 3,500 acres (about 14 square kilometers) of butterfly habitat since 1983. San Bruno Mountain was the first place in the country to use a special plan called a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP). These plans are designed to protect endangered species like the Mission blue butterfly.

How Habitat Conservation Plans Work

The San Bruno HCP started in 1982. Before that, local people had already created San Bruno Mountain State and County Park. This park covered 1,950 acres (about 8 square kilometers) to protect the butterflies. But then, butterflies started appearing on private land too.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service worked with landowners, builders, and local governments to create the first HCP. The idea was to solve problems caused by endangered butterflies living on private property. However, some people still debate whether HCPs are the best solution.

HCPs work like this: Landowners are allowed to build on some of the butterfly's habitat. In return, they agree to take steps to help the butterflies survive in other places. For example, the San Bruno HCP allowed building on 368 to 828 acres (about 1.5 to 3.3 square kilometers). Property owners in these areas had to give land and money to protect and improve habitat elsewhere on San Bruno Mountain. They also pay into a special fund. This fund helps pay for checking on the butterflies, removing unwanted plants, and other tasks on the protected land.

One area on San Bruno Mountain was supposed to be restored for the butterflies. However, this area was colder, wetter, and windier than their preferred habitat. It was also overgrown with an invasive plant called gorse. The Mission blue butterfly needs a plant called lupine to lay its eggs on.

Fighting Invasive Plants for Butterflies

An environmental company called Thomas Reid Associates (TRA) helps carry out the San Bruno HCP. They do studies and monitor the results. TRA works with others to stop invasive plants from taking over butterfly habitat. They started a big project in 1985 to replace the gorse with lupine plants.

Gorse is a very tough plant that can grow up to 20 feet (6 meters) tall and has deep roots. TRA tried different ways to get rid of it, like using special chemicals and burning. But the gorse kept growing back. In 2001, 16 years after the project began, 100 acres (about 0.4 square kilometers) of the original 330 acres (about 1.3 square kilometers) were still covered in gorse.

The Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office also manages conservation areas at San Bruno Mountain and Parkside Homes. Parkside Homes is a newer plan for a 25-acre (about 0.1 square kilometer) neighborhood in South San Francisco. This area has both native plants, like lupines, and non-native ones. The permit for this plan was given in 1996.

The first conservation permit for San Bruno Mountain was issued in 1983. It covered 3,500 acres (about 14 square kilometers) of land. Besides the Mission blue, other endangered animals like the San Bruno elfin butterfly and the San Francisco garter snake live there. Over the years, more land was added to the conservation agreement, including areas in 1985, 1986, and 1990.

Conservation Efforts at Fort Baker

Fort Baker is an old military base near Sausalito, California. The U.S. Army closed the base in 1995, and by 2001, it became part of the National Park Service.

At Fort Baker, about 8.25 acres (about 3.3 hectares) of non-native Monterey pine and tea trees are growing into the Mission blue butterfly's habitat. Protecting this area is a top priority for the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. The plan is to remove these unwanted trees from areas where the butterfly's host plant, Lupinus albifrons, grows. The goal is to make the area completely free of these invasive trees.

Legal Battles and Hotel Plans

There was a long legal fight over what would happen to some of the Fort Baker land. The city of Sausalito and the National Park Service (NPS) were involved. The NPS wanted to allow a group to build a large hotel and conference center on the old base. This idea had been around since the 1980s.

The group, Fort Baker Retreat Group LLC, planned to build a big complex. In 2001, Sausalito sued to stop the project. The city argued that the NPS had not followed environmental laws when planning the project. The NPS's plan included preserving or improving 42 acres (about 170,000 square meters) of habitat, with 23 acres (about 93,000 square meters) specifically for the Mission blue butterfly.

In 2004, a court ruled that Sausalito had the right to sue the NPS. The court said the project could bring up to 2,700 visitors daily, which would affect traffic and income in Sausalito. The court also found that the city had legal standing under the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA) and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).

However, the court also rejected some of Sausalito's other claims. For example, it said the NPS had followed the Endangered Species Act by working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The legal battle ended in 2005 when Sausalito and the Park Service reached an agreement. The hotel project was made smaller, with a maximum of 225 rooms.

Mission Blues at Twin Peaks

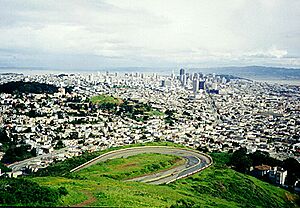

The Twin Peaks in San Francisco are famous landmarks and also home to Mission blue butterflies. The entire area is a park managed by the San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department (SFRPD). The park has 31 acres (about 125,000 square meters) of "Natural Areas." These areas include some of the largest remaining coastal scrub and prairie in San Francisco. These habitats are perfect for the Mission blue butterfly.

Twin Peaks is very popular for its amazing views of the city. It has many different types of habitats, from forests to coastal scrub. Among the coastal scrub and prairies, you can find silver bush lupine plants. These plants are essential because they are where the endangered Mission blue butterflies lay their eggs.

Monitoring and Helping the Butterflies

The Mission blue butterfly was first seen at Twin Peaks in 1979. SFRPD staff confirmed they were still there in 2000 and 2001. They check for butterfly eggs on lupine plants regularly in the spring. In 2000, they found 56 eggs on 115 plants. In 2001, they found 14 eggs on 15 plants. Between 2001 and 2007, only a few adult butterflies and larvae were found. In April 2009, a project tried to bring more butterflies to Twin Peaks by releasing 22 butterflies from the San Bruno population.

In 2006, the San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department released a plan for managing its natural areas. For Twin Peaks, the plan says that protecting the Mission blue butterfly's habitat is a top priority. This includes making sure there are enough silver bush lupine plants. The plan also recommends monitoring the butterfly population and adding more host plants whenever possible.

The Mission blue is the only federally endangered animal at Twin Peaks. However, the Bay checkerspot butterfly is a federally threatened species. The park is also home to about 20 other species that are threatened or endangered at a local level.

Fire and Habitat Restoration

Many people believe that lupine plants, which are the Mission blue's host plants, need occasional disturbances to reproduce well. Natural disturbances like fire are often prevented by humans, especially in areas used for recreation.

Solstice Fire Restoration

In June 2004, the Solstice Fire happened near Sausalito, California. The fire started from a camping accident. It threatened old buildings but spared them. However, a group of non-native Monterey pine trees burned. These pine trees are an invasive species that take over the coastal grasslands that Mission blue butterflies need.

After the fire, over 250 burnt trees were removed. The wood chips from these trees were used to make electricity and to help control cape ivy, another invasive plant. The burned area was then replanted with native plants. This included purple needle grass and 400 summer lupine seedlings. However, these new plants still have to compete with non-native Italian thistle and French broom.

Lateral Fire and Recovery

In August 2004, the "Lateral Fire" also started at Fort Baker. This fire threatened homes, historic buildings, and the Mission blue butterfly's habitat. The fire burned about 300 lupine plants, which are where Mission blues lay their eggs. The U.S. federal government responded to help.

Controlling non-native plants was key to protecting the lupines after the fire. French broom and Italian thistle tried to grow back in the coastal grass and scrubland. French broom needed the most work to prevent its return. Different methods were used, including:

- covering the ground with weed-free straw

- burning with handheld propane torches

- removing or cutting plants with a special tool

These methods were 90% effective on young plants. However, French broom had many seeds, so multiple treatments were needed. A huge new wave of French broom seeds appeared after three burning treatments. Italian thistle was mostly controlled by hand-pulling and using special chemicals.

After the fire, monitoring showed some important things. About half of the lupine plants survived the fire, and even more grew after the fire. Live Mission blue caterpillars were found on some burned lupine plants. This means that the butterflies, even in their early stages, survived the Lateral Fire.

|

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |