Bay checkerspot butterfly facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bay checkerspotEuphydryas editha bayensis |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Nymphalidae |

| Genus: | Euphydryas |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: |

E. e. bayensis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Euphydryas editha bayensis (Sternitsky, 1937)

|

|

The Bay checkerspot (Euphydryas editha bayensis) is a beautiful butterfly that lives only in the San Francisco Bay area of California. It is considered a federally threatened species, which means its numbers are very low and it needs protection. This butterfly is a special type, or subspecies, of the Euphydryas editha butterfly.

Since the 1980s, the number of checkerspot butterflies, including this subspecies, has dropped a lot. Scientists at Stanford University have been studying the Bay checkerspot since the 1960s. They noticed it was in danger, especially because new buildings and roads were taking over its natural home in the San Francisco Bay Area. Because of this, in 1980, they asked the U.S. government to protect this butterfly. After a long discussion, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officially listed it as a threatened species in 1987.

Contents

What the Bay Checkerspot Looks Like

The Bay checkerspot butterfly is a medium-sized butterfly. Its wings can spread a little more than 2 inches (51 mm) wide. It belongs to a group called "brush-footed butterflies."

Its front wings have black lines along the veins on the top surface. These black lines make the Bay checkerspot look unique and give it its name. The black lines stand out against bright red, yellow, and white spots.

The Bay checkerspot is different from other checkerspot butterflies:

- It is darker than the LuEsther's checkerspot (Euphydryas editha luestherae). It also doesn't have the clear red band on its outer wing that the LuEsther's checkerspot has.

- It is not as dark and has brighter red and yellow colors than the island checkerspot (Euphydryas editha insularis). The island checkerspot lives on the Channel Islands and nearby mainland.

- It has more noticeable black bands than other subspecies like the Quino checkerspot (Euphydryas editha quino) or the Mono Lake checkerspot (Euphydryas editha monoensis). This makes it look much more "checkered."

The Bay checkerspot was first described by Robert F. Sternitzky in 1937.

Life Cycle of the Butterfly

Adult Bay checkerspot butterflies appear in early spring. They usually live for about ten days. They emerge over a six-week period, from late February to early May.

Male butterflies usually emerge a few days before the females. Their main goal is to find a mate. They mate with females soon after they emerge. A male can mate many times, but most females mate only once during this time. Besides mating, adult butterflies also look for nectar to eat and, for females, lay eggs.

Eggs are typically laid in March and April. A female butterfly can lay up to five groups of eggs. Each group can have anywhere from 2 to 250 eggs. She usually lays them at the bottom of the dwarf plantain plant. Sometimes, she lays them on owl's clover or paintbrush plants.

The eggs hatch in about ten days. The young larvae (caterpillars) then grow for two weeks or more. During this time, they shed their skin several times. Once they reach a certain stage, they enter a resting period called diapause. This resting period lasts all summer. During diapause, they hide under rocks or in cracks in the soil. When diapause ends, they become active again, eat, and finish growing into adult Bay checkerspot butterflies.

What They Eat

Young caterpillars depend on certain plants for food, mostly the dwarf plantain. Adult butterflies, however, drink nectar from flowers. They feed on many different plants found in special grasslands with serpentine soil.

Some of these plants include California goldfields, white turtlehead, desert parsley, scytheleaf onion, false babystars, and intermediate fiddleneck. How many eggs a female butterfly can lay depends a lot on how much nectar is available.

Where They Live

The Bay checkerspot butterfly is losing its natural home. This is a big reason why it is now a federally threatened species. Like other endangered butterflies in the Bay Area, the checkerspot faces challenges from human development. People are building on areas that used to be perfect homes for these butterflies.

Another major threat is invasive species. These are plants that are not native to the area but grow very well there, taking over the space needed by native plants. However, the biggest threat to the butterfly is likely the increasing amount of nitrogen in the air in California.

Their Home Range

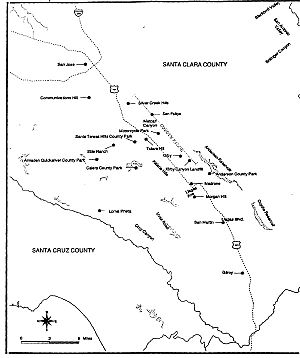

Historically, the Bay checkerspot lived in many areas around the San Francisco Bay. This included most of the San Francisco peninsula, mountains near San Jose, the Oakland Hills, and parts of Alameda County. They were found from Twin Peaks to Mount Diablo in Contra Costa County, all the way south to Hollister.

However, as development increased throughout the 20th century, many of these areas no longer have the butterflies. Today, the only known populations live in Santa Clara County. Changes in natural events like fires, along with invasive plants, have also harmed the host plants the butterflies need.

Their current home range is much smaller and broken up. All the butterfly populations known in San Mateo County when the species was listed as threatened in 1987 have disappeared. In 2007, scientists tried to reintroduce 1000 caterpillars to Edgewood County Park, but a new population did not start there. The butterfly was last seen at San Bruno Mountain in 1985 and at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve in 1998.

All remaining known populations are now in Santa Clara County. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says that any suitable habitat within the historic range should be considered "potentially occupied." One large population, possibly hundreds of thousands strong, is near Morgan Hill on a ridge called Coyote Ridge. Much of this land was bought by the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority and is set to open as Coyote Ridge Open Space Preserve in 2018.

At Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, the local populations died out in 1998. These butterflies were studied closely by Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich since 1960. Researchers looked at 70 years of climate data and found that big changes in local weather likely sped up the disappearance of the Jasper Ridge Bay checkerspot populations. Ehrlich believes that before Spanish settlers came to California, Bay checkerspots were common everywhere. But settlers brought hay for their cattle, which accidentally introduced invasive plants. These new plants competed with the native plants that the Bay checkerspot needed to survive.

The butterfly and its host plants do best in areas with serpentine soil. This is a special type of soil that comes from certain rocks. This habitat usually has three types:

- Primary habitat: Large areas of native grasslands on big serpentine rock formations.

- Secondary habitat: Smaller "islands" of native grasslands on smaller serpentine outcrops. These spots can produce many butterflies when the weather and habitat are good.

- Tertiary habitats: Areas where both the butterfly larvae and their food plants grow in non-serpentine soils that are similar to serpentine soil.

Host Plants: What the Caterpillars Eat

The Bay checkerspot caterpillar needs plants from two different groups to survive. Its main food plant is from the Plantago group, and its backup food plants are from the Castilleja group.

Plantago erecta

Plantago erecta, also known as dwarf plantain, is the main food plant for the Bay checkerspot caterpillar. In many years, this plant dries up early. When that happens, the caterpillars have to find a different plant to eat. P. erecta is native to California and only found in western North America. Since it's the main food source for the Bay checkerspot, it's very important for protecting the butterfly. It's also called California plantain, English plantain, foothill plantain, dotseed plantain, and dwarf plantain. You can usually find it in coastal sage scrub, foothill woodland, and chaparral areas.

Castilleja exserta

Castilleja exserta is known as exserted Indian paintbrush or purple Indian paintbrush. It's one of the two backup food plants for the caterpillars. It stays green later in the spring than the dwarf plantain, so it's there when the main food source dries up. This plant can grow up to 16 inches (410 mm) tall. It likes hillsides and open areas in pine forests and poppy fields, usually at elevations from 1,500 to 4,500 feet. Its flowers bloom from March to May. They are about 1.25 inches long and grow in dense spikes. The flowers are magenta or purple with yellow or white tips. The plant is found from central to southern California, into southern Arizona, and northern Mexico.

Castilleja densiflora

C. densiflora, commonly called purple owl's clover, is the second backup food plant for the caterpillars. Like C. exserta, it often stays green later in the spring than the main food plant. This plant is usually between 4 and 12 inches (100 and 300 mm) tall and grows in small groups. Its flowers can be seen between April and July. They are pink/purple to white/yellow with five petals that form a yellow "beak" and "eyespots" on the lower lip, which looks like an owl's face. You can find this plant in many different places, including foothill woodland, mixed evergreen forest, northern coastal scrub, chaparral, yellow pine forest, and native grasslands.

Protecting Their Home

Many groups, both private and government, are working to protect the Bay checkerspot butterfly. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and Stanford University lead some of the most important projects. In 1984, the USFWS suggested that about 8,300 acres (34 km2) in five different places should be called "critical habitat" for the Bay checkerspot. These areas included San Bruno Mountain, Edgewood County Park, parts of Redwood City, Jasper Ridge, and Coyote Ridge near Morgan Hill.

The USFWS has identified some of these areas as "core habitat areas." These are places they believe are vital for the butterfly's survival. Areas along Coyote Ridge, like Kirby, Metcalf, San Felipe, and Silver Creek Hills, are called "core habitat areas." An area of 1,100 acres (4.5 km2) in the Santa Teresa Hills is a "potential core area." The service also points out other good quality areas near core populations, like Tulare Hill, which are considered "stepping stones" for the butterflies to move between habitats.

The Nitrogen Problem

One interesting challenge in protecting this butterfly is linked to increased nitrogen from air pollution. Serpentine soils, where the butterflies live, naturally have low nitrogen. When more nitrogen is added, it makes these soils more fertile. This allows invasive plants to grow quickly and push out the native plants that the Bay checkerspot needs for nectar.

This is where moderate grazing by cattle can actually help. In a large group of butterflies south of San Jose, when cattle were removed from the grasslands, the butterfly population went down a lot. This is because grazing cattle eat the plants and remove nitrogen from the area when they are taken away for slaughter. So, moderate grazing helps keep nitrogen levels low, which is good for the butterfly.

Increasing nitrogen pollution is a big problem for the delicate balance of ecosystems where the Bay checkerspot lives. At Coyote Ridge, scientist Stuart Weiss has studied this problem. He found that the declining butterfly population there was linked to pollution from the freeway below the ridge and, again, less cattle grazing. Weiss showed how nitrogen oxide from cars made the nutrient-poor serpentine soil richer. This is a clear example of the nitrogen effect. Besides reducing nitrogen, cattle also help control invasive grasses by eating them. Weiss's monitoring equipment shows that 15 to 20 pounds of nitrogen per acre are deposited on Coyote Ridge every year from cars on U.S. Route 101. This nitrogen either sticks to plants and the ground or is absorbed directly by the plants. In contrast, pollution from power plants and vehicles drops only about four to five pounds of nitrogen per acre per year on the Jasper Ridge preserve.

Jasper Ridge

Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve used to have a population of the threatened checkerspot, but it died out in 1998. Paul Ehrlich and his team gathered a lot of information about the Bay checkerspot populations at Jasper Ridge. Now, Stanford University has asked Ehrlich and others to study the butterfly long-term and see if it's possible to bring them back. Professors from different fields are looking at how to restore extinct species or lost habitats. The goal is to figure out if and how to reintroduce Bay checkerspots to Jasper Ridge.

The Jasper Ridge study also aims to understand the rules for endangered species and how changes might help species recover. They are also looking at the genetics of existing butterfly collections and possible donor populations. Plus, they are studying how the ownership, management, and condition of the serpentine grasslands have changed over time.

Coyote Ridge

Coyote Ridge is a ridge in Santa Clara County. Different names are used for areas along the ridge where Bay checkerspots have lived or still live, such as Morgan Hill, Kirby Canyon, East Coyote Foothills, and Coyote Ridge itself. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has identified four main areas along Coyote Ridge that are important for the Bay checkerspot: Kirby, Metcalf, San Felipe, and Silver Creek Hills.

The Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority bought 1,831 acres (7.41 km2) of this land in 2015. This property is planned to open in 2018 as the Coyote Ridge Open Space Preserve.

The Agreement

Before the Bay checkerspot was officially listed as threatened, the USFWS made an agreement with Waste Management of California, Inc. and the city of San Jose. This agreement was made under the Endangered Species Act. It aimed to reduce and make up for any harm to Bay checkerspots caused by building and operating the Kirby landfill in Kirby Canyon, along Coyote Ridge. The landfill is next to a large population of Bay checkerspots.

Key parts of the agreement included:

- Limiting the total area affected, focusing on lower quality habitats.

- Filling the landfill in stages.

- Restoring filled areas with the right plants.

- Leasing 267 acres (1.08 km2) of high-quality habitat for Bay checkerspot protection for 15 years.

- Restoring and managing other Bay checkerspot habitats.

- Monitoring butterfly populations and their habitats.

- Possibly buying more Bay checkerspot habitat for better protection.

In the late 1990s, projects at Kirby Canyon were behind schedule. Efforts to replant areas were slow because the landfill wasn't being filled as quickly as expected. Waste Management completed the ten-year agreement and then offered to fund 50 percent of the agreement for three more years.

Metcalf

Metcalf was named a "Critical Habitat" area by the USFWS in 2001. This area, called the Metcalf Unit, covers 3,351 acres (13.56 km2) in Santa Clara County. It includes one of the four largest habitat areas and three largest current populations of Bay checkerspots. In spring 2000, it had the densest population of Bay checkerspots known. With hundreds of acres of serpentine soils, thousands of butterflies live in this unit. It's considered a main center for the butterfly's larger population in Santa Clara County. The USFWS Recovery Plan for Serpentine Soils Species made protecting this butterfly and its habitat a high priority.

Metcalf is next to Kirby to the south and San Felipe to the east. Silver Creek Hills is to the north, and the Tulare Hill Corridor is to the west. This connection between areas is very important for the Bay checkerspot to spread throughout the Coyote Ridge area. The land in Metcalf is owned by many different groups. Parts are in the city of San Jose and on private lands in Santa Clara County. Parts of the Santa Clara County Motorcycle Park, Coyote Creek Park, and land owned by the Santa Clara Valley Water District are also within the Metcalf Unit.

San Felipe

Mostly on private lands, 998 acres (4.04 km2) of land, called the San Felipe Unit by USFWS, was declared "Critical Habitat" for the Bay checkerspot butterfly in 2001. This land contains the San Felipe population area, which is one of the four largest habitat areas and three largest current populations of Bay checkerspots. The San Felipe area is considered a key part of the butterfly's larger population in Santa Clara County. The USFWS Recovery Plan considered the San Felipe area to be a top priority for conservation. Although there are hundreds of acres of serpentine soils in this unit, including areas for nectar and dispersal, there are no public lands in San Felipe.

Silver Creek

A housing and golf course project led to the creation of the Silver Creek Butterfly Conservation Area. About 1,500 homes and a golf course were built on about 1,500 acres (6.1 km2) in the Silver Creek Valley, east of San Jose. This project caused the loss of about 18.5 acres (75,000 m2) of serpentine habitat for the Bay checkerspot. To make up for this, the developer, Shea Homes, set up a permanent 115-acre (0.47 km2) site for butterfly conservation in the Silver Creek Hills in 1991. The company also paid for ten years of monitoring the preserve. Shea Homes also put $100,000 into an account for regional Bay checkerspot conservation, which is now managed by the USFWS.

With the Silver Creek Butterfly Conservation Area in place, the butterfly population there grew a lot. By 1994, there were tens of thousands of adult butterflies. However, this population crashed in 1995 and 1996 because of problems with managing the area. By 1997, almost no caterpillars were found after their resting period, and only three adults were seen during annual monitoring. Other populations are located on nearby property in the Silver Creek Hills and the nearby San Felipe habitat area.

Edgewood Park and Natural Preserve

Edgewood Park is in San Mateo County, California. It provides a small home for the Bay checkerspot, one of the few left in the state. This habitat is scattered and isolated, like much of the remaining serpentine soil areas for the butterfly. The park is a 467 acres (1.89 km2) woodland and grassland preserve located off Interstate 280. The preserve has hiking trails through its serpentine grasslands.

In 1983, a proposed golf course threatened the preserve. A decision in 1993 helped secure the park's future. That year, the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors decided against the golf course. They passed a resolution that called Edgewood Park "a scenic natural area where outstanding features as well as significant wildlife habitats are preserved in their present state for the enjoyment, education and well-being of the public." At the same time, the county changed its agreement with Midpeninsula Open Space District. They added a rule to prevent golf course development and to focus on preserving natural resources and low-impact recreation.

The Bay checkerspot disappeared from Edgewood Park in the early 2000s, last seen in 2002. This local extinction is thought to be due to nitrogen pollution from cars on Interstate 280. This pollution fertilized invasive Italian ryegrass, which then choked out the native plants the butterflies needed. However, the Italian ryegrass was actually planted on purpose to control erosion after PG&E built high power lines across the park. It then spread into the park from there. Later, people tried to restore the habitat by mowing at the right time of year to reduce the Italian ryegrass and let the native plants grow back. In early 2007, 1000 Bay checkerspot caterpillars were brought back to the park.

San Bruno Mountain

The San Bruno Mountain Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) was created in 1983. It was the first plan of its kind in the United States. This plan covers about 3,400 acres (14 km2) in northern San Mateo County. It aims to protect seven animal species and 44 plant species. Among them are the federally endangered Mission blue and the Bay checkerspot butterfly. However, the Bay checkerspot was not federally listed when the plan was adopted. So, this HCP mainly focuses on the two butterfly species that were federally listed in 1983: the Mission blue butterfly and the San Bruno elfin butterfly. The permit for the plan ends on March 31, 2013. Currently, the plan does not include rules for accidentally harming Bay checkerspots. The Bay checkerspot disappeared from San Bruno Mountain around 1986. This was caused by fires, non-native plant species, and natural changes in their numbers. Bringing the Bay checkerspot back is one of the goals of the San Bruno HCP.

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |