Montgomery Improvement Association facts for kids

The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) was a group started on December 5, 1955. It was formed by Black ministers and community leaders in Montgomery, Alabama. Leaders like Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Edgar Nixon helped guide the MIA.

The MIA played a key role in the Montgomery bus boycott. They set up a car pool system to help people get around. They also talked with city officials to try and find solutions. The MIA taught classes on nonviolence to prepare the community for fair treatment on buses. Even though the group faced challenges and tough times, the boycott succeeded. It brought national attention to unfair racial segregation in the South. This also helped Martin Luther King Jr. become a well-known leader.

Contents

How the MIA Started

After Rosa Parks was arrested on December 1, 1955, for not giving up her bus seat, plans began. Jo Ann Robinson of the Women's Political Council and E. D. Nixon of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) quickly planned a one-day bus boycott for December 5.

On that Monday, the buses were surprisingly empty. This showed how strongly people felt about the issue. The success of the one-day boycott made everyone want to continue. As Martin Luther King Jr. said, the excitement was like a "tidal wave."

That same afternoon, leaders met at the Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church. They decided to form the Montgomery Improvement Association. This new group would manage and continue the boycott. Its main goal was to "improve the general status of Montgomery" and make race relations better.

Choosing a Leader

Martin Luther King Jr., a young minister new to Montgomery, was chosen to lead the MIA. He was only 26 years old. Rosa Parks mentioned that he was picked partly because he was new. This meant he didn't have any enemies in the community yet.

Other important leaders also joined the MIA. Reverend L. Roy Bennett became vice president, and E. D. Nixon was the treasurer. Ralph Abernathy, Jo Ann Robinson, Rufus Lewis, and many others worked alongside King to guide the organization.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

How the Car Pool System Worked

Throughout 1955 and 1956, the MIA organized car pools. They also held weekly meetings with speeches and music to keep the Black community united. The car pool system was huge, using about 300 cars. These cars picked up and dropped off people in different areas during morning and evening hours.

Churches and ministers in Montgomery helped a lot. They offered cars, drivers, and safe places for people to wait. Everyday people also used their own cars to drive boycott participants. This car pool system was the backbone of the boycott. It made sure Black residents could get to work, school, and run errands without using the buses.

How the Boycott Was Funded

Running such a large car pool system was expensive. The MIA needed money to buy more cars, pay drivers, buy gas, and maintain vehicles. They also needed funds for any possible legal fines.

Money came from many places. National civil rights groups from the North and South sent money. International groups also helped. This happened after Jo Ann Robinson sent out a newsletter. It made many people interested in the boycott's success.

However, most of the money came from local people. Members of the African American community in Montgomery regularly gave money at weekly meetings. Groups like "The Club from Nowhere," led by Georgia Gilmore, and "The Friendly Club," led by Inez Ricks, also raised money. They sold baked goods to both Black and white people in the city. These groups were fully dedicated to raising funds for the MIA and the boycott.

Talking with City Leaders

After their first meeting on December 5, the MIA leaders wrote down their demands. They agreed the boycott would continue until these demands were met. Their requests included:

- Bus drivers treating all passengers politely.

- Seating on a first-come, first-served basis.

- Hiring of African American bus drivers.

At first, the MIA was willing to accept a compromise. This compromise was similar to the "separate but equal" idea, not full integration. They were following what other boycott campaigns in the Deep South had done. For example, a successful boycott in Mississippi had happened earlier. It was against gas stations that didn't have restrooms for African Americans.

MIA members presented their demands to Montgomery officials on December 8. But the city rejected them. More meetings on December 17 and 19 also failed. The MIA then realized they needed to change their approach.

They met with the Men of Montgomery (MOM) on February 8 and 13, 1956. The MIA tried to compromise again. They asked for lower bus fares, hiring Black drivers, and five reserved seats for white people. But these demands were also rejected.

After this, the MIA's ideas became stronger. Their transportation committee even suggested creating their own public transportation system. This idea was later turned down by city officials. Finally, MIA lawyer Fred Gray, with help from the NAACP, filed a lawsuit. This lawsuit, called Browder v. Gayle, directly challenged the unfairness of bus segregation in Montgomery.

Life After Integration

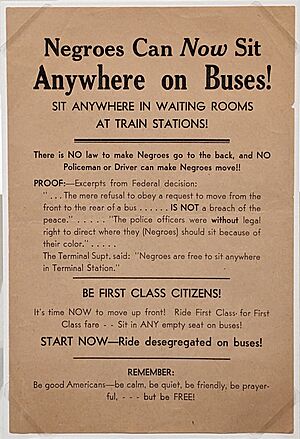

The MIA successfully ended segregation on public transportation in Montgomery. But their work didn't stop there. The Black community still needed to actually start riding the integrated buses.

To help with this, the MIA held nonviolent training sessions every week. These sessions took place in churches and high schools. They prepared people to handle any problems or negative reactions they might face. The MIA also held a week-long workshop called the Institute on Nonviolence and Social Change. This event honored the first anniversary of the boycott and continued teaching nonviolence.

Challenges Faced by the MIA

Even with its success, the MIA faced big problems. It almost fell apart, which would have ended the boycott. Much of this was due to negative reactions from white people. This often showed up as threats and bombings.

These threats didn't stop the MIA or the boycott. But they did cause some damage. Some leaders, especially Martin Luther King Jr., almost quit. One leader, Robert Graetz, even had to move out of Montgomery.

The MIA and its leaders also faced legal challenges in 1956. On February 21, 89 MIA leaders were accused of breaking an Alabama anti-boycott law. However, only Dr. King was tried. He received a small penalty, and the charges against him and the others were dropped.

Perhaps the most dangerous court order against the MIA came on November 5, 1956. Montgomery officials tried to get a court order to stop the MIA's car pool system. If this had happened, Black residents would have had no way to get around. This would have forced them back onto the segregated buses, ending the boycott.

However, the boycott still succeeded. Before the court order could be officially put in place, the Supreme Court made a ruling. On November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that segregation on public transportation was against the law.

Internal Problems

The MIA also almost broke apart because of disagreements within the group. U. J. Fields was the first recording secretary. But he wasn't re-elected because he often missed meetings. In response, Fields publicly claimed on June 11, 1956, that MIA officers were stealing money and becoming too proud.

These claims hurt the MIA's public image. They could have made the group lose trust and funding. However, King handled the situation well. He met with Fields, who then publicly took back his statements. This actually made the organization stronger.

After the Boycott Ended

After its success with the Montgomery bus boycott, the MIA helped create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in January 1957. It joined with the Inter-Civic Council (ICC) and the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) to form the SCLC. The MIA had a lasting impact on the SCLC. The SCLC was designed to work like the MIA, but on a larger, national scale. The MIA also sent five of its own officers to the SCLC, including making Martin Luther King Jr. its new leader.

The MIA lost some of its energy after King moved from Montgomery to Atlanta in 1960. However, the organization continued its work throughout the 1960s. It focused on helping people register to vote, integrating local schools, and opening Montgomery city parks to everyone. The MIA created a ten-point plan called “Looking Forward.” This plan aimed to improve the community, advocating for things like more voter registration and better education and health. Even though it lost some momentum, the MIA did improve life for Black people in Montgomery after the boycott.

The MIA is still active in Montgomery today. Johnnie Carr was its president from 1967 until she passed away in 2008. The modern organization meets monthly. It focuses on community service, offers an annual scholarship, honors the boycott, and helps create civil rights museums and memorials.

People

- Ralph Abernathy

- L. Roy Bennett

- Hugo Black

- James F. Blake

- Aurelia Browder

- Johnnie Carr

- Claudette Colvin

- Erna Dungee

- Clifford Durr

- Uriah J. Fields

- E. N. French

- Georgia Gilmore

- Robert Graetz

- Fred Gray

- Grover Hall Jr.

- T. R. M. Howard

- Debbie Jones formerly Abbie Medlock

- Martin Luther King Jr.

- Coretta Scott King

- Rufus A. Lewis

- Susie McDonald

- E.D. Nixon

- Rosa Parks

- Mother Pollard

- Jo Ann Robinson

- Bayard Rustin

- Glenn Smiley

- Mary Louise Smith

- Jefferson Underwood II

See also

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |