New York City school boycott facts for kids

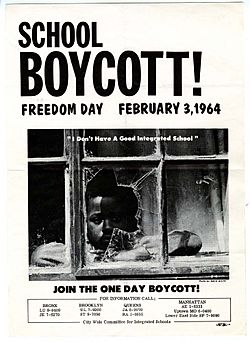

The New York City school boycott, also known as Freedom Day, was a huge boycott and protest against segregation in New York City's public schools. It happened on February 3, 1964. Students and teachers walked out of classes to show how bad conditions were in many city schools. People also held rallies, demanding that schools become integrated.

This event has been called the largest civil rights protest of the 1960s. Nearly half a million people took part.

Why the Boycott Happened

Freedom Day was part of a bigger effort by activists. They wanted to pressure the New York City Board of Education. The Board had not created a good plan to integrate schools. This protest happened after a smaller school boycott in Chicago in October 1963.

Even though school segregation had been against the law in New York City since 1920, schools were still separated. This happened because of where people lived. Schools with mostly Black and Latino students often had worse buildings. They also had less experienced teachers and were very crowded. Some schools even had students attend for only four hours a day.

Some groups, mostly white parents, were against integration. They believed children should go to schools closest to their homes. They were also worried about busing students to different schools.

Just before the boycott, the Board of Education shared a plan. It aimed to integrate schools over three years. This plan included some rezoning and efforts to reduce crowding. It also promised to improve schools for Black and Latino students. But activists who wanted integration felt the plan was not good enough.

A few days before the protest, The New York Times newspaper printed an article. It was called “A Boycott Solves Nothing.” The article criticized the protest leaders. It claimed the boycott would be violent, illegal, and wrong.

Freedom Day: The Big Protest

The boycott was led by Reverend Milton Galamison. He organized a group called the Citywide Committee for Integrated Schools. Many important groups supported him. These included the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality, and the National Urban League.

The committee asked Bayard Rustin to help organize the boycott. Rustin was a well-known activist. He had played a big part in the successful March on Washington in August 1963.

On Monday, February 3, 1964, about 45 percent of all New York City students stayed home. An estimated 464,361 students and teachers joined the boycott. This was even more people than the famous March on Washington.

About 90,000 to 100,000 students who boycotted went to special "Freedom Schools". These schools were set up in churches, community centers, and private homes. Community educators taught lessons there.

Out of 43,865 teachers in the city, 3,357 were absent that day. This was three times more than usual. They did this even though School Superintendent Bernard Donovan had warned them.

Protesters also gathered at the Board of Education building, City Hall, and the office of Governor Rockefeller.

New York's newspapers were surprised by how many Black and Puerto Rican students took part. They were also amazed that the protest was completely peaceful.

What Happened After

The boycott did not immediately force big changes in New York City schools. Another school boycott planned for the next month did not happen. It did not get enough support from people. Still, the event was an important step in a much larger movement for change.

Even though it was a major event in the civil rights movement, the New York City school boycott is not often found in U.S. history textbooks. This might be because it doesn't fit the usual story. That story often focuses on important civil rights events happening mostly in the South.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed five months after the boycott. This law had a special rule that allowed school segregation to continue in big northern cities. These included New York City, Boston, Chicago, and Detroit.

As of 2018, New York City still has some of the most segregated schools in the country.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |