Nihon Ōdai Ichiran facts for kids

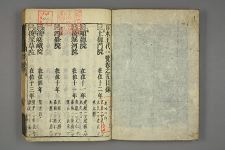

Nihon Ōdai Ichiran (日本王代一覧, Nihon ōdai ichiran), which means The Table of the Rulers of Japan, is a special history book from the 1600s. It lists all the emperors of Japan in order. It also includes short notes about important events that happened during their time.

In the 1800s, this book was one of the very few books about Japan that people in the Western world could read. This was especially true after it was translated into French in 1834.

Contents

About the Book's Creation

The information in Nihon Ōdai Ichiran shows the viewpoint of its original Japanese author. It also reflects the ideas of his powerful supporter, a samurai leader named Sakai Tadakatsu. He was a tairō, which was a very high-ranking official, and also a daimyō (a powerful feudal lord) of the Obama Domain.

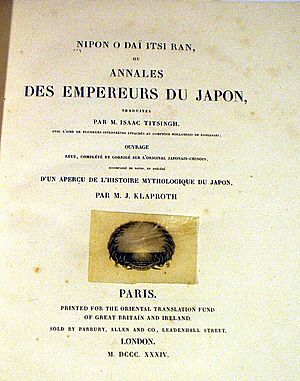

This book was the first of its kind to be brought from Japan to Europe. It was later translated into French with the title "Nipon o daï itsi ran".

A Dutch scholar named Isaac Titsingh brought seven copies of Nihon Ōdai Ichiran with him when he returned to Europe in 1797. He had spent 20 years in Asia. Sadly, these books were lost during the Napoleonic Wars. However, Titsingh's French translation was published after he passed away.

The translation project was put on hold after Titsingh's death in 1812. But it was restarted when the Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland decided to support its printing. A scholar from Paris, Julius Klaproth, helped prepare the text for its final publication in 1834. He also added a supplement that continued the history into the 1700s.

First Japanese History Book Published in the West

Nihon Ōdai Ichiran became the first history book written by a Japanese author to be published and shared for study in the Western world. It was chosen as one of the first books to be scanned and put online as part of the Google Books Library Project. This made it available for many more people to read.

Here is the full title of the French translation:

- Titsingh, Isaac, ed. (1834). [Siyun-sai Rin-siyo/Hayashi Gahō (1652)], Nipon o daï itsi ran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon, tr. par M. Isaac Titsingh avec l'aide de plusieurs interprètes attachés au comptoir hollandais de Nangasaki; ouvrage re., complété et cor. sur l'original japonais-chinois, accompagné de notes et précédé d'un Aperçu d'histoire mythologique du Japon, par M. J. Klaproth. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. ran Click here to read the original text in French.

Titsingh had mostly finished his work on this book by 1783. He sent a copy to his friend, Kutsuki Masatsuna, who was a daimyō. Masatsuna's notes on the text were lost in a shipwreck in 1785. Titsingh wrote the final dedication for the book to Masatsuna in 1807, many years before it was published.

The Original 17th-Century Text

The original book, which had many volumes, was put together in the early 1650s by Hayashi Gahō. His father, Hayashi Razan, had created a popular way of combining Shinto and Confucian ideas. These ideas were used to train and educate samurai and government workers.

In 1607, Razan became an advisor to the second shōgun, Tokugawa Hidetada. Later, he became the head of the Confucian Academy in Edo (now Tokyo), called the Shōhei-kō. This school was the most important part of the education system created by the Tokugawa shogunate, which ruled Japan for many years.

Because of his father's important role, Gahō also became a respected scholar. The connections of the Hayashi family and the Shōheikō helped make Nihon Ōdai Ichiran very popular in the 1700s and 1800s. Gahō also wrote other history books, including The Comprehensive History of Japan, which had 310 volumes and was published in 1670.

The story in Nihon Ōdai Ichiran stops around the year 1600. This was probably done to respect the feelings of the Tokugawa government, which had just come to power. Gahō ended his history just before the last ruler who was not from the Tokugawa family.

Nihon Ōdai Ichiran was first published in Kyoto in 1652. It was supported by Sakai Tadakatsu, one of the most powerful men in the Tokugawa government. It seems that Sakai Tadakatsu had several reasons for supporting this book. He likely also hoped that it would be translated and shared with readers in the West.

Gahō's book was reissued in 1803, perhaps because it was a useful reference for officials. People at the time must have found it helpful. Those who made sure this book reached Isaac Titsingh probably believed it contained valuable information for people in the West.

Later scholars, like Richard Ponsonby-Fane, have used Nihon Ōdai Ichiran as a source of information. Even the American poet Ezra Pound had a copy of the book in his library in 1939. He described it as a "mere chronicle," but modern experts have shown that Pound used Titsingh's French translation when writing some of his poems.

The 19th-Century French Translation

Titsingh's translation was finally published in Paris in 1834. Its title was Annales des empereurs du Japon. The 1834 version included a small "supplement" with information from after Titsingh left Japan in 1784. This extra part was not translated from the original book. Instead, it was likely based on stories or letters from Japanese friends or European colleagues still in Japan.

Titsingh worked on this translation for many years. In his final years in Paris, he shared his progress with other scholars like Julius Klaproth and Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat. They later edited his first book published after his death. Rémusat later became the first professor of Chinese language in France.

Titsingh's letters to his friend William Marsden give us an idea of how much he valued this work. In a letter from 1809, he wrote:

-

- "I offer you the first three volumes of [Nihon Ōdai Ichiran] ... Even though the origins of the Japanese are unclear ..., the detailed story of events sheds much light on their customs. It proves they were already a civilized and educated nation when our modern empires were either unknown or very primitive ... We are not prophets. We cannot predict what will happen in the future. But for now, it is a fact that no one in Europe but me can provide such a complete and accurate account of a nation that is quite unknown here, even though it fully deserves to be known in every way." – Isaac Titsingh

Klaproth dedicated the book to George Fitz-Clarence, the Earl of Munster. He was a leader of the Royal Asiatic Society and the Oriental Translation Fund. This fund had supported Klaproth's work and paid for the book's publication.

See also

In Spanish: Nihon ōdai ichiran para niños

In Spanish: Nihon ōdai ichiran para niños

- Historiographical Institute of the University of Tokyo

- International Research Center for Japanese Studies

- Historiography of Japan

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |