Isaac Titsingh facts for kids

Isaac Titsingh (born around January 1745 – died February 2, 1812) was a Dutch diplomat, historian, and merchant who studied Japan. He had a long career in East Asia, working as a senior official for the Dutch East India Company. This was a big European trading company. He was the only European official allowed to have direct contact with the Japanese government, called the Tokugawa shogunate. He traveled to Edo (now Tokyo) twice to meet the shogun (Japan's military ruler) and other important government officials. He also served as the Dutch governor in Chinsura, Bengal, in India.

Titsingh worked with Charles Cornwallis, who was the governor for the British East India Company. In 1795, Titsingh represented Dutch interests in China. He was welcomed by the Qianlong Emperor's court. This was different from the British diplomat George Macartney's visit in 1793, which was not as successful. In China, Titsingh acted as an ambassador for his country while also being a trade representative for the Dutch East India Company.

Contents

Isaac Titsingh's Early Life

Isaac Titsingh was born in Amsterdam, Netherlands. His father, Albertus Titsingh, was a successful surgeon. Isaac was baptized on January 21, 1745. Because his father was well-off, Isaac received a good education for the 18th century. He became a member of Amsterdam's Barber Surgeon's guild and earned a law degree from Leiden University in January 1765. In 1766, he began working for the Dutch East India Company and moved to Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia).

Life in Japan (1779–1784)

Titsingh was the chief merchant, or "opperhoofd," for the Dutch East India Company in Japan. He held this important role from 1779 to 1780, then from 1781 to 1783, and again in 1784. His position was very important because Japan had a strict policy called "Sakoku," which meant the country was mostly closed off from the rest of the world. This isolation lasted from 1633 to 1853.

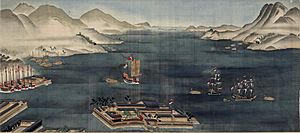

The Tokugawa government had started this "closed door" policy in the early 1600s. This was because Europeans had tried to spread their religion in Japan during the 16th century. Under this policy, no European or Japanese person could enter or leave Japan without risking death. The only exception was the Dutch East India Company's trading post, called a "factory," on the small island of Dejima in Nagasaki Bay. This island is located off the southern Japanese island of Kyūshū. During this time, Titsingh is thought to have been the first Freemason in Japan.

Because of this strict control, the Dutch traders became the only official way for Europe and Japan to trade and exchange scientific and cultural ideas. The Dutch chief merchant was treated like a special visitor to the shogun. Titsingh had to make an official annual visit to the shogun in Edo twice. These opportunities were rare, so Titsingh's informal meetings with Japanese officials and scholars in Edo were just as important as his formal meetings with the shogun, Tokugawa Ieharu.

During the 18th century, the Dutch merchants were treated with more respect by the Japanese. However, most Dutch chiefs were not interested in Japanese customs or culture. Titsingh was different. He showed great interest and carefully observed Japanese civilization, much more than his colleagues in Dejima.

Titsingh arrived in Nagasaki on August 15, 1779. He took over the trading post from Arend Willem Feith. Titsingh built good relationships with the Japanese interpreters. Before he arrived, there had been many arguments over trade and strong dislike for the Japanese interpreter, who the Dutch traders thought was corrupt. During his first meeting with Shogun Ieharu in Edo, from March 25 to April 5, 1780, Titsingh met many Japanese lords, called daimyo. He later exchanged many letters with them. He became very well-known among the elite in Edo and became friends with several important daimyo.

After a short trip back to Batavia in 1780, Titsingh returned to Nagasaki on August 12, 1781. This was because he had been so successful with Dutch-Japanese trade in Dejima. In 1782, no Dutch ships arrived from Batavia due to the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. This meant the trading post in Dejima was cut off from communication with Java. During this year, Titsingh stayed in his role as chief merchant. He focused on making friends with Japanese scholars, strengthening his relationships with Japanese friends, and researching Japanese customs and culture. Because there were no Dutch ships that year, he also had important trade talks and gained big agreements from the Japanese to increase copper exports to the Dutch traders.

Titsingh stayed in Japan for a total of three years and eight months. He finally left Nagasaki at the end of November 1784 and arrived back in Batavia on January 3, 1785.

Life in India (1785–1792)

In 1785, Titsingh was made the director of the trading post in Chinsurah, Bengal (India). William Jones, a scholar and judge in Bengal, called Titsingh "the Mandarin of Chinsura." This meant he was a very knowledgeable and important official.

Time in Batavia (1792–1793)

When Titsingh returned to Batavia, he took on new roles. He became the Treasurer and later the Maritime Commissioner, overseeing sea matters.

While in Batavia, he met George Macartney, a British diplomat who was on his way to China. Titsingh's advice was important in Macartney's decision not to try to visit Japan in 1793. Macartney later wrote that Titsingh, a "Dutch Gentleman of a very liberal disposition," had lived in Japan for several years. Macartney learned that while a visit to Japan might not be well-received, it was worth trying, especially since the Dutch East India Company's trade with Japan was declining.

Mission to China (1794–1795)

Titsingh was chosen to be the Dutch ambassador to the Emperor of China. This was for the celebrations of the Qianlong Emperor's sixtieth year as ruler. In Peking (now Beijing), Titsingh's group included Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest and Chrétien-Louis-Joseph de Guignes. Both of them later wrote about this important visit to the Chinese court.

Titsingh's difficult journey in mid-winter from Canton (now Guangzhou) to Peking allowed him to see parts of inland China that Europeans had never seen before. His group arrived in Peking just in time for the New Year's celebrations. The Chinese treated Titsingh and his group with unusual respect and honors in the Forbidden City and later at the Yuanmingyuan (the Old Summer Palace).

Titsingh is believed to have been the first Freemason in China. He was also the only one to be welcomed at the court of the Qianlong Emperor.

Return to Europe (1796–1812)

On March 1, 1796, the Dutch East India Company, which was already struggling, was taken over by the new Dutch government, called the Batavian Republic. In that same year, Titsingh returned to Europe. For a while, he lived in Britain, in London and Bath. He became a member of the Royal Society, a famous group of scientists. In 1801, he went back to Amsterdam, and then to Paris, France, where he lived until he died.

Titsingh died in Paris on February 2, 1812. He is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery. His gravestone says: "Here lies Isaac Titsingh. Former councilor of the Dutch East Indies. Ambassador to China and Japan. Died in Paris on February 2, 1812, aged 68 years."

Family Life

Titsingh had a son named Willem, born around 1790, whose mother was Titsingh's Bengali mistress. Titsingh brought his son to Europe in 1800 so that he could be recognized as his legal child. When Titsingh moved to Paris, Willem went with him and attended the French Maritime Academy, graduating in 1810.

Isaac Titsingh's Collections

Titsingh's personal library and his collection of art, cultural items, and scientific materials were sold off after his death. Some of them became part of the French national collections. Among the Japanese books Titsingh brought to Europe was a copy of Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu (An Illustrated Description of Three Countries) by Hayashi Shihei. This book, published in Japan in 1785, described Joseon (now Korea), the Ryukyu Kingdom (now Okinawa), and Ezo (now Hokkaido). In Paris, this book was the first time the Korean writing system, Hangul, was seen in Europe. After Titsingh's death, the original book and Titsingh's translation were bought by Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat. Later, Julius Klaproth published his edited version of Titsingh's translation in 1832.

Isaac Titsingh's Legacy

Isaac Titsingh was a unique person for the Dutch East India Company. He was seen as a philosopher and the most thoughtful of all the company's employees in Japan. He wrote many private letters about religion and human topics. He worked hard to share knowledge between Europe and the outside world, especially Japan. He was a true 18th-century philosopher.

Compared to other company employees, he spoke many languages: Dutch, Latin, French, English, German, Portuguese, Japanese, and Chinese. He was very excited to introduce European society to Japanese customs and culture because he loved Japan. He became an important person who helped share knowledge and culture between Japan and Europe. For example, he brought Dutch books about European knowledge to Japan. He also collected original materials about Japan, which became the first European collection on Japan. This collection included books, manuscripts, prints, maps, city plans, and coins. This collection formed the basis for a unique history of Japan.

This "Cabinet Titsingh" collection was made up of two-dimensional items. Because of this, Isaac Titsingh is seen as the founder of European Japonology, which is the study of Japan. He wanted to have a friendly exchange of knowledge. He even urged Dutch East India Company officials to send learned employees who could speak Japanese to the trading post in Dejima. He believed this would improve relations between Europeans and Japanese in Dejima, as he wrote in a letter on August 28, 1785.

Titsingh was also one of the first Europeans to translate Japanese poems into Latin verses. These translations, along with an essay on Japanese poetry, can be found in his collection of works on Japanese customs and culture, called Bijzonderheden over Japan/Illustrations of Japan.

Because he was a "traveling philosopher," Titsingh was a member of several important societies: the Royal Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences, the Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen in Haarlem, the Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta, and the Royal Society of London.

Sadly, Titsingh's work and collections were somewhat lost after his death. He couldn't find Japanese or Chinese translators in Europe to help him with his collected materials. His own knowledge of Chinese and Japanese writing was limited. He could only edit the translations of Japanese accounts that he and others had already prepared in Dejima. Most of his work was published after he died, and it was only a small part of his larger collection. Also, some parts were changed a lot by his editors and publishers. This happened because after his son Willem went bankrupt, Titsingh's collections and manuscripts were sold and spread across Europe in the 19th century.

Titsingh's experiences and research led to published articles and books. The Batavian Academy of Arts and Sciences published seven of his articles about Japan.

His descriptions of how to make sake (Japanese rice wine) and soy sauce in Japan were the first to be published in a Western language. His work became more widely known throughout Europe by the early 19th century.

Titsingh also put together an early Japanese dictionary. This was just the beginning of a project he worked on for the rest of his life.

Isaac Titsingh's Values

Titsingh was very eager to get answers to his scholarly questions and had an incredible desire for knowledge. Looking at his private letters, we can see three main values that guided him:

- He rejected money because it didn't satisfy his great thirst for knowledge.

- He understood that life is short and didn't want to waste this precious time on meaningless activities.

- He wished to die peacefully, as a "forgotten citizen of the world."

These values show that he was like a European philosopher of the 18th century. He was also interested in his Japanese fellow scholars and respected their intelligence. He helped create a strong exchange of cultural knowledge between Japan and Europe in the 18th century.

Selected Works

Here are some of the books and articles connected to Isaac Titsingh:

- 1781 – "Bereiding van saké en soya" (Preparation of sake and soya), published in Transactions of the Batavian society of arts and sciences.

- 1819 – Cérémonies usitées au Japon pour les mariages et les funérailles (Ceremonies Performed at Marriages and Funerals in Japan).

- 1820 – Mémoires et anecdotes sur la dynastie régnante des djogouns, souverains du Japon (Memories of and Anecdotes about the Reigning Dynasty of Shoguns, Sovereigns of Japan). This book included descriptions of festivals and ceremonies, and details about Japanese poetry.

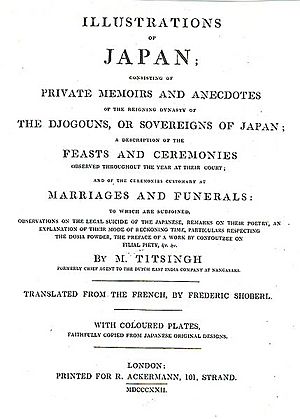

- 1822 – Illustrations of Japan; consisting of Private Memoirs and Anecdotes of the reigning dynasty of The Djogouns, or Sovereigns of Japan. This English version included descriptions of feasts, ceremonies, marriages, and funerals, along with notes on poetry.

- 1834 – Nihon Ōdai Ichiran (Annals of the Emperors of Japan). This was a translation by Titsingh, completed and corrected by Julius Klaproth.

- 2006 – Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779-1822, a modern English edition of the 1822 work Illustrations of Japan, edited by Timon Screech.

See also

In Spanish: Isaac Titsingh para niños

In Spanish: Isaac Titsingh para niños

- An'ei – The Japanese historical period when Titsingh visited Japan.

- Foreign relations of imperial China

- Royal Society – Titsingh became a member in 1797.

- Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest – A Dutch merchant who joined Titsingh's mission to China from 1794 to 1795.