Nikolai Leskov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nikolai Leskov

|

|

|---|---|

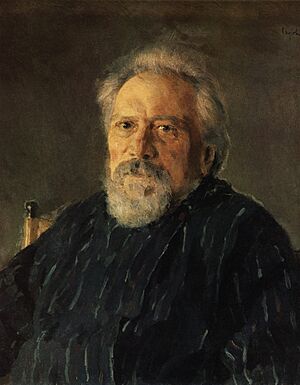

Portrait of Leskov by Valentin Serov, 1894

|

|

| Born | Nikolai Semyonovich Leskov 16 February 1831 Gorokhovo, Oryol Gubernia, Russian Empire |

| Died | 5 March 1895 (aged 64) St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Pen name | M. Stebnitsky |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, skaz writer, journalist, playwright |

| Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Period | 1862–95 |

| Literary movement | Realism |

| Notable works | Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk The Cathedral Folk The Enchanted Wanderer "The Steel Flea" |

| Spouse | Olga Vasilievna Smirnova (1831–1909) |

| Partner | Ekaterina Bubnova (née Savitskaya) |

| Children | Vera Leskova Vera Bubnova-Leskova (adopted), Andrey Varya Dolina (aka Varya Cook, adopted) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Nikolai Semyonovich Leskov (Russian: Никола́й Семёнович Леско́в; February 16, 1831 – March 5, 1895) was a famous Russian writer. He wrote novels, short stories, plays, and worked as a journalist. Sometimes he used the pen name M. Stebnitsky.

Many important writers like Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov admired Leskov. He was known for his special writing style and new ways of telling stories. Leskov created a detailed picture of Russian society during his time, mostly through his shorter works. Some of his most famous stories include Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (1865), The Cathedral Folk (1872), The Enchanted Wanderer (1873), and "The Steel Flea" (1881).

Leskov went to school in Oryol. Later, he worked in a court office and then for a trading company. This job allowed him to travel a lot across Russia. He learned about different people and their ways of speaking. These experiences greatly influenced his writing. His first stories were published in the early 1860s. Many of his later works were not allowed to be published because they made fun of the Russian Orthodox Church. Leskov passed away on March 5, 1895, when he was 64 years old. He was buried in Saint Petersburg.

Contents

About Nikolai Leskov's Life

His Early Years and Education

Nikolai Semyonovich Leskov was born on February 4, 1831, in a village called Gorokhovo. His father, Semyon Dmitrievich Leskov, was a respected court official. His mother, Maria Petrovna Leskova, came from a noble family. Nikolai's family on his father's side were all church leaders.

Nikolai spent his first eight years in Gorokhovo. He learned from tutors who taught his cousins. In 1839, his father lost his job. The family moved to a small village and lived a simpler life. This is where Nikolai first heard the unique Russian ways of speaking that he later used in his books.

In 1841, Leskov started school at the Oryol Lyceum. He didn't do very well and only got a two-year certificate. Some people thought he didn't like the strict school rules. They believed he preferred learning about real life.

Starting His Career

In 1847, Leskov began working at the Oryol criminal court office. His father had worked there before. In 1848, a fire destroyed his family's home. That same year, his father died. In 1849, Leskov moved to Kiev. He worked as a clerk and lived with his uncle, who was a doctor.

In Kiev, he attended university lectures. He learned Polish and Ukrainian languages. He also studied icon-painting. He met many different people, including pilgrims and religious groups. In 1853, Leskov married Olga Smirnova. They had a son who died young and a daughter named Vera.

In 1857, Leskov left his government job. He started working for a private trading company called Scott & Wilkins. This company was owned by his aunt's Scottish husband, Alexander Scott. Leskov traveled a lot for this job. He went through many parts of Russia. He learned about local customs and different ways of speaking. These travels gave him many ideas for his stories. He once said that these years were the best of his life. He saw so much and learned about many different people.

Becoming a Journalist

Leskov started writing in the late 1850s. He wrote detailed reports for his company. He also wrote personal letters to Alexander Scott. Scott noticed Leskov's writing talent. He showed his letters to a writer who thought they should be published. Leskov's first important writing was an essay about the wine industry. It was published in 1861.

In 1860, he moved back to Kiev. He wrote for different newspapers. One of his articles was about corruption in police medicine. This caused problems, and he lost his job. In 1861, Leskov moved to Saint Petersburg. He joined the staff of a liberal newspaper called Northern Bee. He wrote under the name M. Stebnitsky. He wrote about daily life and also criticized certain ideas of the time.

In May 1862, Leskov wrote an article about large fires in Saint Petersburg. Rumors were spreading that students and Poles caused the fires. Leskov asked the authorities to say if the rumors were true or not. This article made both the public and the government unhappy. The newspaper sent Leskov on a long trip to Paris as a correspondent. He visited several cities and translated some stories.

Nikolai Leskov's Writing Career

His First Published Works

Leskov's writing career truly began in 1862. His story "The Extinguished Flame" was published. Then came the short novels Musk-Ox and The Life of a Peasant Woman in 1863.

In 1864, his first full novel, No Way Out, started to be published. Leskov later said it was written quickly. The novel made fun of certain groups and praised traditional values. This upset some critics. They thought Leskov was against their ideas. Some even spread rumors that the government paid him to write it. This made it hard for Leskov to get his works published in popular magazines. However, conservative magazines welcomed him.

His Most Important Stories

Leskov wrote Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in 1864. It was published in 1865. This story, along with his novella The Amazon (1866), showed strong female characters. They were ignored by critics at the time. But later, people realized they were masterpieces. Both stories used a special folk-like writing style called skaz. Leskov was known for this unique style.

In 1870, Leskov published At Daggers Drawn. This novel also criticized certain social movements. Many critics did not like his "political" novels. Leskov himself later said this novel was a failure. He felt that the publisher interfered too much.

The Cathedral Folk was published in 1872. This book was a collection of stories about Russian priests and nobles. It was a big change for Leskov. It focused on the good side of people. It showed the difference between the simple faith of ordinary people and the official church. This book caused a lot of discussion. It made both the government and church leaders unhappy.

In 1873, The Sealed Angel was published. It was a story about a miracle that brought a group of Old Believers back to the main church. This story was influenced by old folk tales. It is now seen as one of Leskov's best works. It used his unique skaz style very well.

Also in 1873, The Enchanted Wanderer came out. This story had many different plotlines woven together. It was not a traditional novel. Later, scholars praised the main character, Ivan Flyagin. They saw him as a symbol of the strength of the Russian people. However, critics at the time found the story too disorganized.

In 1874, Leskov got a job with the Ministry of Education. He helped choose books for libraries. This helped him with his money problems. He continued to write stories about good people. He said these characters were based on real people he had met. He didn't like to make things up.

Later Works and Challenges

In 1881, The Tale of Cross-eyed Lefty from Tula and the Steel Flea was published. This story is considered one of Leskov's greatest works. It showed his amazing storytelling skills. It was full of clever wordplay and new words. The story made fun of some things in a humorous way. It was attacked by both sides: some said it was too nationalistic, others said it showed a gloomy picture of common people.

Leskov continued to write stories about good, working people. He also wrote legends from early Christianity. Some of these stories were translated into German, which made him very proud.

In 1883, an essay he wrote about a drunken pastor caused a scandal. Leskov lost his job at the Ministry of Education. After this, the Russian Orthodox Church became a main target of his satire. He wrote about how he felt the church's teachings were being twisted. He became close with Leo Tolstoy in the 1880s. Leskov admired Tolstoy's ideas about "new Christianity."

Many of Leskov's later works were banned by censors. For example, his novel The Unseen Trail was stopped in 1884. His novella Zenon the Goldsmith was banned in 1888. This made it very hard for him to publish his works. He felt isolated. He said his later stories were "cruel" because they showed the harsh truths of life. He wanted to make people think, not just please them.

In 1888, Leskov met Anton Chekhov. Ilya Repin, a famous artist, also became his friend. Repin wanted to paint Leskov's portrait. In 1889, a publisher started releasing Leskov's collected works. But some volumes, especially those criticizing the church, were stopped by censors. Leskov had a heart attack when he heard this news. Despite the problems, the publication continued, and he earned good money.

His 1891 story Polunochniki (Night Owls) also caused an uproar because it criticized the Orthodox Church. His 1894 novella The Rabbit Warren was banned and only published much later. Publishing his works was always difficult for Leskov.

His Final Years

In his last years, Leskov suffered from heart and breathing problems. In early 1894, he got a bad cold. His health got worse. He agreed to pose for a portrait by Valentin Serov. But when he saw the finished portrait, he was very upset by it.

Nikolai Leskov died on March 5, 1895, at the age of 64. His funeral was quiet, as he had wished. He was buried in the section for writers at the Volkovo Cemetery in Saint Petersburg. Leskov was known for being a bit difficult. He spent his last years mostly alone. His son, Andrey, later wrote a detailed book about his father's life.

Leskov's Family Life

On April 6, 1853, Leskov married Olga Vasilyevna Smirnova. She was the daughter of a wealthy trader. They had a son, Dmitry, who died as a baby. Their daughter, Vera, was born in 1856. Leskov's marriage was not happy. His wife had serious mental health issues. She was later taken to a hospital.

In 1865, Ekaterina Bubnova became Leskov's partner. She had four children from her first marriage. Leskov adopted one of her daughters, also named Vera. He made sure she got a good education. In 1866, Ekaterina gave birth to their son, Andrey.

In 1878, Leskov and Ekaterina separated. Nikolai moved with his son, Andrey. Ekaterina was very sad about her son being taken away. Later, in 1883, a young girl named Varya Dolina, who was his maidservant's daughter, joined Leskov's household. She became another of his adopted daughters.

Andrey Leskov became a military officer. He later became an expert on his father's writings. He wrote a very detailed book about Nikolai Leskov's life. This book was even rebuilt from scratch after being destroyed during a war.

Nikolai Leskov's Importance in Literature

Nikolai Leskov is now seen as a very important Russian writer. However, his writing career was often difficult. He faced many scandals and was sometimes ignored by critics. At the time, writers often had to pick a side in political discussions. Leskov never fully joined any group. This meant he didn't get much support from critics.

Despite this, many readers loved his books. In the 1870s, things got a bit better for him. But even then, critics often ignored him. However, his collected works sold very well. After his death in 1895, he had few friends in literary groups but many readers across Russia.

In the early 1900s, there was new interest in Leskov's work. A famous writer named Maxim Gorky praised Leskov greatly. Gorky called him "the wizard of wording." He said Leskov was a brilliant writer who understood Russian life deeply.

For many years after his death, critics had mixed feelings about Leskov. Some of his sharpest stories could only be published after the 1917 Russian Revolution. Soviet leaders didn't always like his work. They sometimes called him "reactionary" because he didn't support social revolution. They preferred stories like "Lefty" that showed Russian talent.

However, interest in Leskov grew after World War II. More studies were done on his work. His son's biography was published. By the 1980s, Leskov was finally seen as a major Russian classic. His works were studied alongside those of Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy.

His Ideas and Beliefs

Leskov's writings often showed real life in 19th-century Russia. He knew a lot about different parts of Russia. He understood local ways of life, industries, and religious groups. He thought that other writers, who only studied people from books, didn't truly understand them. Leskov believed that writers should "live" among the common people.

He cared about social problems. But he believed that education and religious teachings were the way to improve society. He didn't think a revolution would help. Unlike some other writers, Leskov didn't feel sorry for peasants in a distant way. He knew Russian life from his own experiences.

Some modern experts say Leskov was not "reactionary" at all. They believe he was a democratic thinker. He hoped for good changes after serfdom ended in 1861. But he was disappointed by how slow things changed. He often wrote about the old ways that held Russia back.

Leskov, like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, saw the Gospel (the teachings of Jesus) as a guide for humanity. He believed it was the basis for all progress. His "saintly" characters showed this idea of spreading goodness. However, he sometimes used religious stories to talk about current problems in a lighthearted way.

In his later years, Leskov was influenced by Leo Tolstoy. He developed his own idea of "new Christianity." He felt very close to Tolstoy's way of thinking. Leskov's Christianity was against strict church rules. It focused on humility and kindness. He believed that being too proud was a big mistake.

His Unique Writing Style

Leskov once said that people would read his stories for their ideas in the future. But critics now say he is read for his amazing writing style. Many writers, including Anton Chekhov, learned from Leskov. Chekhov admired how Leskov packed so much into his short stories. Leskov was also one of the first to recognize Chekhov's talent.

Maxim Gorky greatly admired Leskov's writing. He saw Leskov as one of the few Russian writers who had their own ideas and the courage to express them. Gorky said Leskov was a master of using lively, everyday Russian speech. He believed Leskov had no equal in this skill.

Leskov often experimented with different forms of writing. He liked "the chronicle" style. He felt it was a better way to tell stories than a traditional novel. He believed life doesn't follow a neat plot. So, his stories reflected that. They were concise and didn't have unnecessary parts.

One common criticism of Leskov's writing was that it was "too colorful." His language was very expressive. Leo Tolstoy, who admired Leskov, still thought he used too many words. But Leskov defended his style. He said his characters spoke like real people. He had listened to Russians talk for years.

Critics sometimes called Leskov a "collector of anecdotes." This is because his stories were often based on strange or funny real-life events. Leskov liked to group his stories into cycles. He created a full picture of Russian society using mostly short stories.

Leskov was fascinated by the lives and customs of different groups in Russia. He had an amazing memory for language. He believed that a writer finds their voice by learning the voices of their characters. He also said that people show their true character in small things.

He preferred to base his stories on real facts, not made-up ones. He saw literature as a kind of history. He believed history was important for a healthy society. Most of Leskov's characters were based on real people. Leo Tolstoy once told Leskov, "Truth can indeed be made to be more thrilling than fiction, and you surely are the master of this art." Many people believe Leskov understood the Russian people better than anyone else.

See also

In Spanish: Nikolái Leskov para niños

In Spanish: Nikolái Leskov para niños