Nino Tkeshelashvili facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

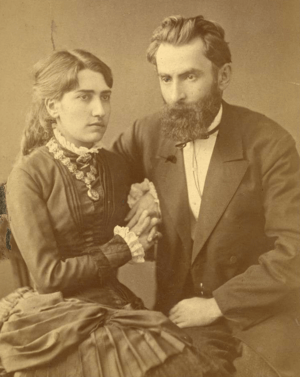

Nino Tkeshelashvili

|

|

|---|---|

| ნინო ტყეშელაშვილი | |

|

|

| Born | 1874 Tbilisi (Tbilisi), Caucasus Viceroyalty, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 1956 (aged 81–82) Tbilisi, Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic

|

| Nationality | Georgian |

| Occupation | teacher, writer, women's rights activist |

| Years active | 1903-1950s |

Nino Tkeshelashvili (Georgian: ნინო ტყეშელაშვილი, 1874–1956) was a Georgian teacher, writer, and activist for women's rights. She was born in 1874 into a family that loved learning. After finishing school in Tbilisi, she taught Russian language in a town called Didi Jikhaishi.

In 1903, Nino went to Moscow to study dentistry. There, she joined students who were part of a movement for change during the 1905 Russian Revolution. She returned to Tbilisi the next year and met other women writers and activists. These women were fighting for equal rights for women.

Nino joined the Union of Georgian Women for Equal Rights in 1906. Three years later, she left this group and helped start the Caucasian Women's Society. This new group was made up of feminists, who are people who believe in equal rights for women.

As the leader of the new society, Tkeshelashvili worked hard for many causes. She fought for women's suffrage, which means women's right to vote. She also worked to improve education for workers and poor people. Her group helped women get better jobs and go to college. They also cared about women's health. Around 1912, she started writing for magazines and newspapers, focusing on issues important to women.

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, feminists hoped the new Georgian Republic would give women equal rights. But instead, the government created a group called the Zhenotdel in 1919. This group limited how much women could freely take part in society. Nino and other feminists kept fighting for equality. However, when Stalin's government took over, the Zhenotdel was closed, and their efforts were stopped. Nino then focused on writing, mostly for children during the Soviet era. After the Soviet Union ended, Georgian feminists rediscovered Nino Tkeshelashvili's story and the stories of other early activists.

Early Life and Education

Nino Tkeshelashvili was born in 1874 in Tbilisi (then called Tiflis). This city was part of the Russian Empire at the time. Her father came from a family of priests and worked in farming. He loved to read. Her mother was a relative of the famous poet Akaki Tsereteli.

From a young age, Nino loved reading books from her father's library. She was also influenced by revolutionaries who often visited her parents' home. These visitors included a journalist named Ilia Bakhtadze and a novelist named Leo Kiacheli. Nino listened to their talks and dreamed of going to high school in Russia, like her brother. She finished her local school and even earned a medal. However, she could not attend teacher training courses right away.

Through her parents, Nino met Niko Nikoladze and his wife, Olga Guramishvili-Nikoladze. Olga was one of the first Georgian women to study abroad. She studied in Switzerland and then returned to Georgia to work in pedagogy, which is the study of teaching. Olga became a mentor to Nino. She encouraged Nino to become a Russian-language teacher at the school Olga ran in Didi Jikhaishi.

Besides teaching, Nino took part in literary evenings and read many books from Nikoladze's library. In 1903, she finally went to Moscow to attend dental school. There, she became involved in student movements for democratic changes. At the end of the 1905 Russian Revolution, Tsar Nicholas agreed to create the Duma. This group had the power to make laws and protected freedoms like speech and assembly for citizens.

Activism and Writing Career

Nino Tkeshelashvili returned to Tbilisi in 1906. She found that the movement for more civil and political rights had grown in Georgia. She lived in a boarding house where she met Mariam Demuria. Mariam was a journalist who gave public lectures and ran a Sunday school for workers. She hired Nino to teach Russian language classes.

Through her work with Mariam, Nino met many other women writers, like Ekaterine Gabashvili. These women were part of the feminist movement. Nino joined the Union of Georgian Women for Equal Rights. This group planned a conference for all Russian women in Tbilisi in 1908. Nino gave the opening speech, asking women to work for their freedom and cultural growth.

After the conference, Nino and a group of women decided they wanted a more international approach to women's rights. In 1909, they left the Union of Georgian Women and formed the Caucasian Women's Society (CWS). There were 135 founding members, including Gabashvili, Babilina Khositashvili, Nino Kipiani, and Kato Mikeladze.

The CWS supported women's right to vote. They also set up clubs for working women where they taught reading, writing, and sewing. Nino hosted literary evenings where people discussed classic Russian books. The CWS also worked to uphold women's "moral standards." They invited women to debates about social issues like education for the poor, job conditions, higher education, and women's health.

Around 1912, Nino Tkeshelashvili started publishing her own writings and translations. She wrote for magazines like Trace and the children's magazine Jejili (meaning "wheat shoots"). She also joined the editorial team of The Stream, where she met writers Nino Nakashidze and Akaki Tsereteli. Writing under the pen name Suffragist, Nino published articles that called for women to have equal political and civic rights.

During World War I in 1914, the Caucasian Women's Society opened free canteens and sewed clothes for soldiers. Nino also wrote more, publishing in journals like The Rock and Voice of Georgian Woman. One of her articles, A Woman at the Front of Revolutionary Culture, talked about how women depended on men financially. It also discussed how social roles kept women tied to their families. She believed that Lenin's revolutionary ideas would free women from unfair laws.

Nino Tkeshelashvili took courses at the Kutaisi Women's Gymnasium. Between 1917 and 1918, she was active in the Georgian independence movement. This happened after the Russian Empire fell apart at the end of the 1917 Revolution. When the Democratic Republic of Georgia was being formed, she took part in local elections for the Social Democratic Party of Georgia. She was surprised that out of 20 candidates, only one was a woman. When she spoke about this, the party leader asked her to name qualified women. Nino gave him five names, but none were added to the ballot.

Because of this, Nino and other members of the Caucasian Women's Society stopped working with the Social Democratic Party. They realized the party was not truly interested in their goals. Instead, the party started promoting its own policies and became less friendly to groups started by ordinary people. In 1919, the Zhenotdel was created. This group put government policies into action from the top down, ignoring what women really needed.

The feminists continued to fight strongly for their rights. They met in private homes to discuss how to keep their struggle going. At one meeting, Nino presented a story called Mourning Birds Celebration. Other women acted out the parts. It was a story that used symbols to represent the feminist struggle. After this, the other women called her the Swallow, which she used as a new pen name. In 1924, she wrote and took part in a public mock-trial called Judging Christine. In this play, she protested against the old capitalist ideas that still harmed women. The performance was very popular and was shown in theaters and workers' palaces.

In 1930, Stalin ended the Zhenotdel. This effectively stopped the women's movement. Officially, a woman's main job became motherhood and housework. Being productive in society was seen as a secondary role. Feminists, who had been seeking equality, then turned to writing children's fiction. This was an approved activity for women. From that time, Nino Tkeshelashvili wrote short stories and fables for children. These were published in Georgian magazines and newspapers. Her best works were Hooks and Alamosa. Other well-known pieces included Elephant and Predators, Mourning Birds, and Donkey.

Later Life and Legacy

Nino Tkeshelashvili passed away in her hometown in 1956. Like most feminists of her time, her work for women's rights was largely forgotten during the Soviet era. Her biography from 1990 listed her as a writer. However, since the Soviet Union broke apart, Georgian feminists have been looking into their past. They are now bringing back the stories of early contributors like Nino Tkeshelashvili.

See also

In Spanish: Nino Tkheshelashvili para niños

In Spanish: Nino Tkheshelashvili para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |