Obovaria retusa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Obovaria retusa |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Dried valves | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Unionida |

| Family: | Unionidae |

| Genus: | Obovaria |

| Species: |

O. retusa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Obovaria retusa (Lamarck, 1819)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The ring pink mussel (Obovaria retusa) is a very rare type of freshwater mussel. It belongs to the Unionidae family, also known as river mussels. People sometimes call it the golf stick pearly mussel.

This mussel used to live in many states, including Alabama, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and West Virginia. By 1991, scientists thought only about five groups of these mussels were left. These were in Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia. Now, it's believed they are gone from West Virginia. Only a few ring pink mussels have been seen recently. If any groups are still alive, they are likely in the Green River in Kentucky.

Contents

What is the Ring Pink Mussel?

The ring pink mussel (Obovaria retusa) is a type of freshwater bivalve. This means it's a mollusk with two shells, like a clam. It is part of the river mussel family, Unionidae. These mussels are naturally found in the eastern and southeastern parts of the United States. Today, you might find them in Alabama, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

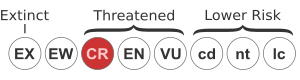

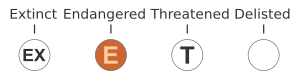

In 1989, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the ring pink mussel as an endangered species. This means it's at high risk of disappearing forever. It is still listed as endangered today.

What Does the Ring Pink Mussel Look Like?

The ring pink mussel was first described in 1819 by a French scientist named Jean-Baptise Lamarck. This mussel has a medium to large shell. Its shells can be oval or square in shape.

The outside of the shell, called the periostracum, is smooth and doesn't have stripes. It can be yellow-green to brown. Older mussels usually have darker brown or black shells. The inside layer of the shell, called the nacre, is a beautiful salmon or deep purple color with a white edge.

Ring Pink Mussel Life Cycle

We don't know a lot about the exact life cycle of the ring pink mussel. However, we can learn from other freshwater mussels.

Most freshwater mussels have tiny larvae called glochidia. When a female mussel is pregnant, she releases these glochidia from her gills. After they are released, these tiny larvae attach themselves to the gills or scales of freshwater fish. They act like tiny parasites for several weeks or months. We don't know if the ring pink mussel needs a special type of fish or if it can use many different kinds.

While attached to the fish, the larvae change and grow into young mussels. This change is called metamorphosis. After they have grown enough, they let go of the fish. The young mussels then sink to the bottom of the river, called the benthos, and start living on their own.

It usually takes about 2 to 9 years for a freshwater mussel to be old enough to reproduce. Some freshwater mussels only lay eggs once every 7 years. The average lifespan for a freshwater mussel is quite long, from 60 to 70 years.

Ring pink mussels carrying glochidia have been seen in late August. Their glochidia are described as "rather large and hookless."

Overall, ring pink mussels, like other freshwater mussels, live a long time. They give birth to live young (this is called ovoviviparous reproduction). They also become able to reproduce later in life and don't have many successful reproduction events.

Ring Pink Mussel Ecology

What Do Ring Pink Mussels Eat?

We don't know exactly what the ring pink mussel eats. But it probably eats the same things as other freshwater mussels. Freshwater mussels often eat tiny bits of dead plants and animals (called detritus), tiny algae (like diatoms and phytoplankton), and tiny animals (like zooplankton).

Where Do Ring Pink Mussels Live?

The ring pink mussel lives in medium to large rivers. They like to live on the river bottom where there is silt, sand, and gravel. They usually don't live in water deeper than about one meter (about three feet).

Where Are Ring Pink Mussels Found?

In the past, the ring pink mussel was found in the Ohio River and its smaller rivers (called tributaries). This included areas in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama.

However, their range has shrunk a lot because of dams built on rivers. Today, the ring pink mussel is found or believed to be found only in Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky.

Why is the Ring Pink Mussel Endangered?

How Many Ring Pink Mussels Are Left?

Building dams on large rivers has caused the number of ring pink mussels to drop. In 1991, a plan to help the ring pink mussel said there were only five known groups left. But since the early 1990s, very few ring pink mussels have been seen. In the last 15 years, only two live ring pink mussels have been found. Both were in the Green River in Kentucky.

It's hard to find these mussels using normal ways, so there might be small groups still living that we don't know about.

The 1991 recovery plan also said that the five groups of mussels that were left were old and probably not reproducing. A recent report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services says that there are likely no groups left that can reproduce. Studies show that when there are fewer freshwater mussels, it can be harder for them to reproduce. This might explain why their numbers dropped so quickly. Since there are no reproducing groups, it's unlikely their population will grow.

Past and Current Locations

In the past, the ring pink mussel was spread out across the Ohio River and its smaller rivers. These rivers went through Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama.

By 1991, only five groups of ring pink mussels were known. They were in Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia. Since 1998, only four sightings of the ring pink mussel have happened, all in the Green River in Kentucky. As of 2019, it's thought that a small group in the Green River is the only one left. Some people think there might also be ring pink mussels in the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers.

Main Dangers and Human Impact

The ring pink mussel is very sensitive to changes in its home. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services said in 1991 that building dams is a major reason why the ring pink mussel is endangered. Dams reduce the gravel and sand habitats that the ring pink mussel likes. Dams also mess up the mussel's life cycle by making it harder for their host fish to reach them. Digging up gravel from rivers (called gravel dredging) and keeping river channels clear also destroy the ring pink mussel's home.

Besides losing their homes, commercial mussel fishing is also a danger. Sometimes, ring pink mussels are accidentally caught when people are fishing for other types of mussels.

Protecting the Ring Pink Mussel

Endangered Species Act Listing

Since September 29, 1989, the ring pink mussel has been listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. This law helps protect species that are at risk of extinction.

Reviews of the Mussel's Status

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services has done two main reviews every five years to check on the mussel's status and how well recovery efforts are working.

A review in 2011 looked at five main threats to the ring pink mussel's home. These threats included too much use of resources, diseases, predators, rules, and other human or natural factors. Between 1998 and 2011, only three ring pink mussels were found. Because of these results, the 2011 review said the ring pink mussel should stay on the endangered list.

Another review was published in 2019. It also looked at similar threats and said there was no need to change the mussel's endangered status. Both reviews agree that the ring pink mussel is at high risk. Experts believe it will be hard for the species to recover.

Recovery Plan Goals

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Recovery Plan aims to change the ring pink mussel's status from endangered to threatened. This means it would still be at risk, but less so. However, full recovery is not thought to be possible right now. It's hard to guess when this change might happen. Mussels don't reproduce until they are about 5 years old. It takes more than 10 years to see if they are reproducing and if the population is healthy.

Experts need to study how commercial fishing affects the mussels. Some river areas might need to be made into mussel safe zones. Since it's hard to find these mussels, experts suggest looking for them in the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers where there might be good habitats.

One idea is to find out which fish species the ring pink mussel uses as a host. Then, they could raise young mussels in labs and release them into rivers where other mussels live. For example, another mussel, the round hickorynut, uses the eastern sand darter (Ammocrypta pellucida) as a host. This might mean the ring pink mussel uses the western sand darter (Ammocrypta clara) or the eastern sand darter. Another idea is to start studies on freezing mussel eggs and larvae. This could help save them since it's hard to get them to reproduce naturally.

Images for kids

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |