Perry Expedition facts for kids

The Perry Expedition was a special trip made by the United States Navy to Japan in 1853 and 1854. It was led by Commodore Matthew C. Perry. His main goal was to end Japan's long-standing policy of staying isolated from the rest of the world. Japan had been closed off for over 200 years!

President Millard Fillmore sent Perry to Japan to open up trade and build friendly relationships. Perry used a bit of "gunboat diplomacy," meaning he showed off the power of his ships to encourage Japan to agree. This expedition was a huge moment. It helped Japan connect with Western countries and led to big changes in Japan, like the end of the old government and the start of the Meiji Restoration. After this, Japanese art and culture even started to influence art in Europe and America, a trend called Japonisme.

Contents

Why the Expedition Happened

Many things led President Fillmore to send an expedition to Japan. American ships were trading more with China, and American whalers were often in the waters near Japan. Also, European countries were taking control of places where ships could stop for coal. America wanted its own coaling stations.

Americans also believed in something called Manifest Destiny. This was the idea that it was their destiny to expand across North America and share the benefits of Western civilization with other nations. By the early 1800s, Japan's policy of isolation was being challenged more and more. In 1844, the Dutch King William II even sent a letter to Japan. He told them to end their isolation before someone forced them to. Between 1790 and 1853, at least 27 U.S. ships tried to visit Japan, but they were always turned away.

Foreign ships were seen more often in Japanese waters. This caused a lot of debate in Japan about how to protect their country. In 1851, the American Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, wanted to return 17 Japanese sailors who had been shipwrecked. This seemed like a good chance to start trade with Japan. Webster wrote a letter to the "Japanese Emperor." He said the expedition was not for religious reasons. It was only to ask for "friendship and commerce" and coal for American ships. The letter also talked about America's growth and its new technologies.

The first commander chosen for the mission was replaced. Then, Matthew C. Perry was chosen. He was a very experienced officer in the U.S. Navy.

Getting Ready for Japan

Perry knew it would be hard to open relations with Japan. He had studied a lot about Japan. He also talked to a famous expert on Japan named Philipp Franz von Siebold. Siebold had lived and worked on a small Dutch trading island in Nagasaki for eight years.

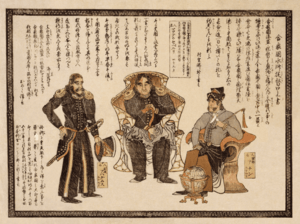

Perry also got special permission to have "full and discretionary powers." This meant he could use force if the Japanese treated him badly, like they had other American visitors before. Perry did not allow any professional diplomats to join his trip. Instead, he brought artists and a photographer to record everything. He also brought some Japanese people who had been shipwrecked to help as interpreters.

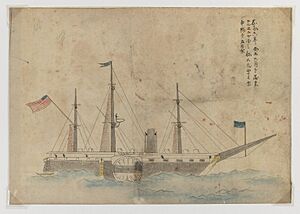

The expedition had several ships. These included steam warships like the Mississippi, Susquehanna, and Powhatan. Perry chose officers he had worked with before. He also brought gifts for the Japanese, including modern weapons like rifles and pistols.

First Visit to Japan (1853)

Perry chose the Mississippi as his main ship. He left Virginia on November 24, 1852. He made several stops around the world, including Singapore and Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, he met an American expert on China who helped translate his letters into Chinese. He then went to Shanghai, where his letters were translated into Dutch.

Perry then sailed to the Ryukyu Islands (now part of Japan). He ignored local rules and used threats to get trading rights and land for a coaling station. He even landed his Marines and drilled them on the beach to show off American power. Perry carefully avoided meeting low-ranked officials. He used military ceremonies and invited people onto his ships to show both American strength and peaceful intentions. He left the Ryukyu Islands with promises that they would be open to trade with the United States.

Showing Force and Talking

Perry finally reached Uraga, at the entrance to Tokyo Bay, on July 8, 1853. His fleet had four ships. He ordered his ships to sail past Japanese defense lines towards the capital city of Edo. He also fired blank shots from his 73 cannons, saying it was to celebrate American Independence Day. Perry's ships had new cannons that could cause huge explosions.

Japanese guard boats surrounded the American ships. Perry ordered his men to stop any attempts to board. A Japanese boat carried a sign in French telling the American fleet to leave. The next day, Japanese officials came to Perry's ship. They told him that foreign ships were not allowed in Japanese ports. Perry stayed in his cabin and refused to meet them. He sent word that he had a letter from the U.S. President and would only meet with high-ranking officials.

On July 10, a Japanese official, pretending to be a higher-ranked officer, met with Perry's captain. He told them to go to Nagasaki, which was the only port for foreign contact. Perry's captain said that unless a suitable official came to receive the letter, Perry would land troops and march on Edo. The Japanese official asked for three days to respond. The real Japanese commander reported to the Shogun (Japan's military ruler) that their defenses were too weak to fight the Americans.

Meanwhile, Perry started to intimidate the Japanese. He sent boats to explore the area and threatened to use force if Japanese guard boats did not leave. He also gave the Japanese a white flag and a letter. It said that if they chose to fight, the Americans would win.

The Japanese government was in a difficult situation. The Shogun was ill, and there was no clear decision on how to handle this threat. On July 11, a senior Japanese leader, Abe Masahiro, decided that simply accepting a letter would not violate Japan's independence. This decision was sent to Uraga. Perry was asked to move his fleet to a beach at Kurihama. There, on July 14, he was allowed to land.

Perry went ashore with great ceremony. He landed with 250 sailors and Marines, after a 13-gun salute from his ship. The Marines presented their weapons, and a band played "Hail Columbia." President Fillmore's letter was officially received by two high-ranking Japanese officials. Perry's ships then left on July 17 for China, promising to return for a reply.

After Perry left, there was a big debate in the Japanese government. The Shogun died days after Perry's departure. The new Shogun was young and sick, so the Council of Elders led by Abe Masahiro was in charge. Abe felt Japan could not fight the Americans. But he also did not want to make a decision alone. To get support, Abe asked all the important Japanese lords (daimyō) for their opinions. This was the first time the government had asked for public debate on such a big decision. This made the government look weak.

The opinions of the lords were split. Some wanted to accept the American demands, and some were against it. Others gave unclear answers or suggested temporary agreements. The only thing everyone agreed on was that Japan needed to improve its coastal defenses right away. Forts were quickly built near what is now Odaiba to protect Edo from another American attack.

Second Visit to Japan (1854)

Perry had told the Japanese he would return the next year. But he soon learned that a Russian admiral had visited Nagasaki after he left. The Russian tried to force Japan to sign a treaty before Perry returned. Perry also heard that the British and French planned to join him to make sure America did not get special deals. So, Perry returned to Japan earlier than planned, on February 13, 1854. This time, he had eight ships and 1600 men.

By the time Perry returned, the Japanese government had decided to agree to almost all of President Fillmore's demands. However, the Japanese negotiators delayed for weeks about where to hold the talks. Perry wanted to meet in Edo, but the Japanese offered other places. Perry eventually got angry and threatened to bring 100 ships (more than the actual size of the US Navy at the time) to Japan to start a war.

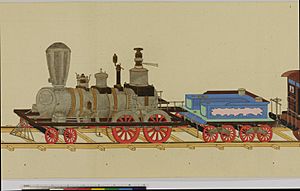

Both sides finally agreed on the small village of Yokohama. A special building was built there for the negotiations. Perry landed on March 8 with 500 sailors and Marines. Three bands played "The Star-Spangled Banner." Three weeks of talks followed, along with exchanging gifts. The Americans gave the Japanese a miniature steam locomotive, a telegraph machine, farm tools, and small weapons. They also gave whiskey, clocks, and books about the United States. The Japanese gave gold-decorated furniture, silk clothes, and porcelain cups. They even gave Perry a collection of seashells because they heard it was his hobby. Both sides also put on cultural shows. American sailors performed a minstrel show, and Japanese sumo wrestlers showed off their strength.

Finally, on March 31, Perry signed the Convention of Kanagawa. This agreement opened the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American ships. It also said that shipwrecked sailors would be cared for and that an American consulate (a type of embassy) would be set up in Shimoda. After signing, Perry sent one ship home with the treaty. The rest of his fleet went to explore Hakodate and Shimoda. After leaving Japan, the fleet returned to the Ryukyu Islands. There, Perry quickly wrote and signed another agreement with the Ryukyu Kingdom on July 11, 1854.

Perry's Return Home

When Perry returned to the United States in 1855, Congress gave him a reward of $20,000 (which would be about $737,000 today). Perry used some of this money to write and publish a three-volume report about the expedition. It was called Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan. Perry was also promoted to the rank of rear-admiral after he retired, because his health was failing. He suffered from severe arthritis and gout, which caused him a lot of pain.

Perry spent his last years working on his book about the Japan expedition. He finished it on December 28, 1857. He died a few months later, on March 4, 1858, in New York City.