Operation Fritham facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Fritham |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arctic Campaign of the Second World War | |||||||

Global view of Norway (Svalbard circled) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Einar Sverdrup (killed 14 May 1942) | Dr Erich Etienne (killed 23 July 1942) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 82 men SS Selis (transport ship) SS Isbjørn (icebreaker) |

4 Focke-Wulf 200 Condors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 12 killed 15 wounded 2 died of wounds |

4 (23 July 1942) | ||||||

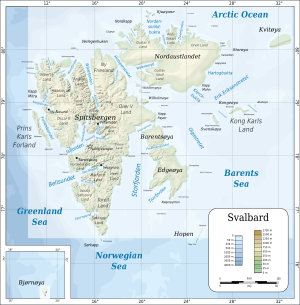

Operation Fritham was a secret mission during World War II. It took place from April 30 to May 14, 1942. The goal was for Allied forces to take control of coal mines on Spitsbergen. This island is part of the Svalbard Archipelago, far north in the Arctic Ocean. The Allies wanted to stop Nazi Germany from using these islands.

A group of Norwegian soldiers sailed from Scotland on April 30, 1942. They planned to take back the island and remove a German weather team. On May 14, four German planes attacked. They sank the Norwegian ships in Green Harbour. The mission leader, Einar Sverdrup, and eleven others were killed. Eleven more soldiers were hurt. Most of their supplies were lost with the ships.

On May 26, a Catalina flying boat named P-Peter arrived at Spitsbergen. The crew found the surviving Norwegian soldiers. They also destroyed a German Ju 88 bomber on the ground. More flights brought supplies. They also attacked German weather bases. Wounded soldiers were taken away. Shipwrecked sailors were rescued.

Later, another mission called Operation Gearbox took over. This happened after two British warships, HMS Manchester and HMS Eclipse, brought 57 more Norwegians and many supplies. Operation Gearbox II started on September 17. By autumn, the Allies had a strong hold on Svalbard. The Navy used Spitsbergen as a temporary base. It helped refuel ships protecting convoys in the Arctic.

Contents

Svalbard's Importance

The Svalbard islands are in the Arctic Ocean. They are about 650 miles (1,050 km) from the North Pole. These islands have tall, snowy mountains. Some even have glaciers. There are also flat areas near rivers and coasts. In winter, the islands are covered in snow. The bays freeze over.

Spitsbergen Island has many large bays called fiords. Isfjorden is one of them. It can be up to 10 miles (16 km) wide. The Gulf Stream warms the waters. This means the sea is free of ice in summer. Towns like Longyearbyen and Barentsburg were built along Isfjorden.

People from different countries settled on the islands. A treaty in 1920 made the islands neutral. It also gave countries rights to mine and fish there. Before 1939, about 3,000 people lived there. Most were Norwegian and Russian. They worked in the coal mining industry. Coal was dug from mines. It was then moved to the coast using special cables or rails. Coal gathered in winter was shipped out when the ice melted in summer. By 1939, about 500,000 tons of coal were produced each year. This was shared between Norway and Russia.

German Weather Stations

After a mission called Operation Gauntlet in 1941, the British thought Germany might take over Svalbard. But Germany was more interested in weather information. The Arctic is where much of Europe's weather comes from. By August 1941, the Allies had shut down German weather stations in Greenland and other islands. They also stopped civilian weather reports from Spitsbergen.

Germany used weather reports from submarines and planes. But these were easy to attack. So, the German Navy and Air Force looked for land sites. They wanted to set up weather stations that could be supplied by sea and air. Some would have people, others would be automatic. A German air unit called Wekusta 5 was based in northern Norway. They flew planes like the He 111 and Ju 88 over the Arctic Ocean. They gained experience in moving supplies for weather stations.

In September 1941, the wireless station on Spitsbergen stopped working. German planes then saw that the Canadians had destroyed things. They also saw one man who had refused to leave. Dr. Erich Etienne, an explorer, led a plan to set up a manned station. Winter was coming. Advent Bay was chosen because it had a wide valley. This made it safer for planes to land. The ground was also good for a landing strip. The Germans used a hut as a control room. They called the site Bansö. Flights began on September 25.

The British knew about these German plans. They used secret information from decoded German messages. Four British ships were sent to investigate. They arrived at Isfjorden on October 19. A German plane saw the ships. The thirty men at Adventfjorden were quickly flown to safety. Adventfjorden was empty when the British arrived. They found some German code books. When the British left, the Germans returned.

After 38 supply flights, Dr. Albrecht Moll and three men arrived. They spent the winter of 1941–1942 sending weather reports. On October 29, 1941, another German team was set up in north-western Spitsbergen. Landing planes in winter was risky. Soft snow could stop a plane. It could also hide holes that could damage the plane.

On May 2, 1942, a German plane dropped off an automatic weather station. It was called a Kröte ("toad"). This station had a thermometer, barometer, and radio. It was powered by batteries. It would send weather data. The plan was to fly it to Bansö. Then the Moll team would be brought back. On May 12, the weather was good enough. A He 111 and a Ju 88 were sent. The Heinkel plane landed carefully. It almost tipped over in the snow. The ten crew and passengers joined the ground team. They had been alone for six months. The Ju 88 pilot was warned away and returned to Banak.

Planning the Mission

British Reconnaissance Flights

In early 1942, the British Navy became interested in Svalbard again. Norwegians wanted to fix their coal mines. They expected a big demand for coal after the war. The Norwegians offered a small group of men. These men were from Svalbard and knew the Arctic well. They also offered two ships, Selis and Isbjørn. The Norwegians said their men only needed basic training. They were returning home, not invading. This would respect the Svalbard Act (1925). The Norwegians' local concerns matched the British Navy's strategic interests. A reconnaissance flight by a Catalina plane was planned.

On April 4–5, a Catalina flying boat flew to Svalbard. On board were Major Einar Sverdrup and Lieutenant Sandy Glen. They were to check the settlements. They also looked for a possible convoy route. They checked for ice in the fiords. And they looked for signs of German presence. Isfjorden was sunny when the plane arrived. Sverdrup and Glen saw the coal dumps still smoking from earlier demolitions. But there was no smoke over Longyearbyen. No footprints were seen in the snow. Sverdrup and Glen reported that the islands were empty. They said a landing would be easy. The 2,500-mile (4,000 km) trip took 26 hours.

On April 11, another flight was ordered. It was to find the edge of the ice. At Longyearbyen, they saw fallen conveyor pylons. These were also from the earlier demolitions. Near some buildings, they saw two masts and tracks. The pilot followed ski tracks. He then spotted a He 111 plane with people around it. The Catalina gunners fired many rounds. They claimed to have destroyed the bomber. They also said they hit some men and a hut. To save fuel, the British plane turned back. It reached Shetland at 4:00 p.m. Their report was sent to the Navy.

The Heinkel pilot later found his plane had only been hit by thirty bullets. None of the 14 men were hurt. The plane was damaged but could still fly. The pilot and wireless operator got on board. They flattened the snow by taxiing back and forth. This packed the snow under the wheels. It took full power to move at first. But after six runs, it could take off. The plane reached Banak. The bullet damage was worse than first thought.

On May 12, another ice survey was ordered. A Catalina crew flew the mission. They flew from the Shetland Islands to Jan Mayen. They checked the ice edge. Then they flew to Isfjorden. They saw smoke over Barentsburg. Photographs showed no footprints. Moments after warning a German Ju 88 not to land, the Germans at Bansö heard another plane.

The Plan for Operation Fritham

The British and Norwegians planned Operation Fritham. A group of 92 men would sail from Scotland. They would use the ice-breaker D/S Isbjørn and the sealer Selis. They would stop in Iceland to get supplies. The group included soldiers from the Norwegian Brigade. It also included Lieutenant Sandy Glen and Major Amherst Barrow Whatman, a wireless expert.

British spies listening to German messages found out that German planes had flown over Svalbard on April 26 and 27. On May 3, the flight plan for the Catalina was changed. It would now include a look at Isfjorden. It would also try to land Glen and Godfrey at Cape Linné. Sverdrup was warned about Germans at Kings Bay. So, a landing there was canceled. The ships headed for Isfjorden to land at Green Harbour. The ice there might have melted.

The ships were strong. Each had a 20 mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun. But no one had been trained to use them. The wireless equipment was not good. Whatman fixed it, but he didn't think it would work far from Jan Mayen Island. It broke down on the way to Iceland. Glen and Godfrey flew to Iceland by Catalina. They met the expedition there. The ships sailed on May 8. They had a copy of the ice report. The ships had to take a more easterly route. But they could stay close to the polar ice. This meant less chance of being seen by German planes. On April 30, 1942, Isbjørn and Selis sailed from Scotland.

Operation Fritham in Action

May 13–15

The Norwegian ships reached Svalbard on May 13. They entered Isfjorden at 8:00 p.m. But they did not get the warning about German planes. A group went ashore at Cape Linné. They found no signs of people. The ships then sailed east along Isfjorden. They found they could not reach Advent Bay because of ice. The ships turned south to Green Harbour. They planned to land at Finneset instead.

The bay was covered in ice up to 4 feet (1.2 m) thick. Isbjørn could break the ice, but very slowly. Godfrey wanted to unload the ships right away. He wanted to use sledges to move supplies ashore. But Sverdrup ordered a rest break first. The men had been cooped up on the voyage. Ice breaking was delayed until after midnight on May 14. Teams were sent to scout Barentsburg and Finneset.

At 5:00 a.m., a German Ju 88 plane flew from Cape Linné to Advent Bay. It flew along Isfjorden at 600 feet (180 m). The plane did not change its course. But the ships must have been seen. The scouting teams found no one. But it took them until 5:00 p.m. to get back. By then, Isbjørn had cut a long channel in the ice. But it was still far from Finneset. Sverdrup wanted to go to the landing stage at Barentsburg. He thought it would be faster to unload there.

After breaking through ice for 15 hours, at 8:30 p.m., four FW 200 Condor bombers appeared. The valley sides were high, so the bombers arrived without warning. They almost hit the ships on their first two bombing runs. The bombs bounced on the ice before exploding. Return fire from the Oerlikon guns had no effect. The third bomber hit Isbjørn, which sank right away. Selis soon caught fire. Some men were thrown into the air by explosions. Others jumped onto the ice. The gun crew fired back at the bombers.

The men scattered to avoid the bombers' machine-gun fire. The Condors flew away after about thirty minutes. Nothing was left of Isbjørn but a hole in the ice. Selis was still burning. Thirteen men were dead, including Sverdrup and Godfrey. Nine men were wounded. (Two of them died later from their wounds.) Sixty members of the group survived unharmed. The cargo in Isbjørn was lost. This included weapons, ammunition, food, clothes, and the wireless.

Barentsburg was only a few hundred yards across the ice. The evacuation eight months earlier had left the houses untouched. Plenty of food was found. It was a Svalbard custom to stock up before winter. Flour, butter, coffee, tea, sugar, and mushrooms were found. An infirmary was also found for the wounded. It still had medical supplies. German Ju 88 and He 111 bombers returned on May 15. But the Fritham party hid in mine shafts.

May 16–31

Most days, a German plane flew east towards Advent Bay or north to Kings Bay. The time it took for the return flight showed that the planes had landed. This suggested that both places were occupied by Germans. When the damaged Heinkel flew back to Banak on May 13, twelve men were left behind. German weather planes were sent to Isfjorden to drop messages and supplies. One of the early flights saw the two Fritham ships. They thought they were Soviet special forces. This led to the Condor attack.

A flight on May 15 found that the second ship was still burning. The German team at Bansö had marked a runway on the ice in Advent Bay. The bomber managed to land and take off. This started the supply flights needed to get the Kröte (automatic weather station) working. The Heinkel pilot, who had been shot at by the Catalina, flew along the west coast. He wanted to avoid a risky climb over the mountains. He also wanted to look at Barentsburg. The second ship had sunk. There were tracks around buildings, but no people. Most important, there were no tracks to Longyearbyen. This meant landing would not be disturbed. The Heinkel landed on the ice. But the pilot saw puddles. This meant the ice was unsafe. The ground team used a tractor to pull sledges with supplies from the plane. The Kröte worked as soon as it was turned on. The Heinkel returned to Banak.

Other planes flew to Svalbard. But the puddles became holes. On May 18, a Heinkel snagged a wheel as it landed. Its propeller was damaged. The landing gear sank further. The plane was stuck. Flights had to be canceled until the airstrip at Bansö was clear of snow and dry. Until then, the German weather team was stuck.

On their flights, the German crews saw ski tracks in Coles Valley. They flew over Barentsburg. They were on their way to drop supplies to the team at Bansö. Command of the Norwegians went to Lieutenant Ove Roll Lund. He sent 35 men to Sveagruva. The journey took the fastest skiers 36 hours. One man was lost down a deep crack in the ice. The fitter men stayed behind. They cared for the wounded. They kept low when German planes were around. They made plans for attacks once they got more help.

Small groups went out on May 16 and 17. They scouted the Germans in Advent Bay. They had light equipment. They used white sheets for camouflage. They lived off supplies in huts along the way. From Barentsburg, the groups moved to Cape Laila. They crossed Coles Valley to the mines. The groups met on the south-east slopes of Longyearbyen. From there, they could watch the airstrip at Bansö.

The Norwegians could see the German team. Several men went to the Hans Lund Hut. They quietly left when they heard a generator. Another group burst into a different hut. They were met by a dog. The dog was calmed when Glen said "Hello." (The dog was named "Ullo.") The groups could not hide their ski tracks at Coles Valley. But they criss-crossed them to confuse the Germans. They returned to Barentsburg unharmed. They were sure the Germans were not strong enough to attack. The wounded looked forward to a Catalina plane arriving.

A signal station was set up in a hut north of Barentsburg. It was near Cape Heer and the mouth of Green Harbour. This was in case a British plane flew down Isfjorden. The three watchers had shelter and warmth. They had a mine entrance for a quick escape. A signal lamp was fixed. It was powered by batteries. The three men waited. They hoped they would not signal a German plane by mistake. By the end of May, the two sides were in temporary bases. They were in fiords south of Isfjorden. They were only ten minutes' flying time apart. But the land journey between them was too rough for a serious trip. The Germans were only 500 miles (800 km) from their base. They had radio contact. They were sure of help once their landing strip dried. The Norwegians had come home. But help was 1,000 miles (1,600 km) away. And they had no way to contact anyone.

Reconnaissance and Supply Flights

May 25

The British Navy received no message from the Fritham party. On May 22, a Catalina crew was told to scout Spitsbergen. They were to check Isfjorden, Cape Linné, Barentsburg, Advent Bay, and Kings Fjord. They were not told that the Navy already knew what had happened from secret messages. The flight started at 11:38 a.m. on May 25. They flew under the clouds. They reached the South Cape of Spitsbergen at 11:10 p.m. The sun had not fully set.

The crew took photos up the west coast to Isfjorden. Drifting ice meant a landing was not possible. At Longyearbyen, the crew saw signs of the demolitions from Operation Gauntlet. Then they saw the He 111 plane that had been damaged on May 18. It was still on the ice. The pilot flew the Catalina west along Isfjorden. Near Green Harbour, they saw smoke. Then they saw the channel cut by Isbjørn. The smoke was coming from coal dumps. A light was seen flashing near some huts. Messages were passed until 1:45 a.m. Then the Catalina had to turn for home. It flew through freezing fog. It landed at 2:27 p.m. on May 26. The situation of the Fritham Force was discovered. The ice edge from Bear Island to Spitsbergen Island was also surveyed.

May 28–29

Landing in a fiord would have to wait until the ice melted. Parachuting supplies from a Catalina was not possible. Bags would have to be dropped from the plane's side windows. They would be dropped into snowdrifts. This would happen during low, slow passes. The bags would have long orange streamers. They would be filled with items that were hard to break. Carrying the extra weight and fuel for such long flights meant the crew dumped everything not essential. This included their parachutes.

The crew expected the party would be eating frozen food. They packed medical supplies, clothing, and comforts. They also packed a Thompson gun and a flare gun with ammunition. And they packed a signaling code. P-Peter took off at 4:32 p.m. on May 28. It flew into fog. It used radar to avoid freezing fog. It flew at heights between 150 and 380 feet (46–116 m). They reached land after 4:00 a.m. on May 29. The Catalina flew at 100 knots (190 km/h). The bags were dropped near huts. The crew watched for German planes. Receiving lamp signals from the ground was hard. The Fritham party could hear a German plane above the clouds. They were not sure which plane to reply to. At 6:40 a.m., P-Peter turned for home. It had a tailwind. It was back at Sullom Voe by 5:00 p.m. The flight took 24 hours and 38 minutes.

June 6–7

Catalina P-Peter took off at 7:21 a.m. for Spitsbergen. It carried 24 Ross rifles and 3,000 rounds of ammunition. It also had food, medical supplies, and mail. It flew low again. The clouds were higher than usual. The crew saw what looked like a He 111 at 11:21 a.m. They reached the island by 5:01 p.m. The bags were thrown out. Then the Catalina landed. Two men went ashore with the mail and other supplies. The crew on the boat pushed away ice floes. The six wounded Norwegians were brought out by boat. The boat was sent back with rum, cigarettes, and tobacco.

The landing party returned with reports at 8:00 p.m. The Catalina was airborne ten minutes later. It reached Sullom Voe at 7:17 a.m. The wounded were taken to the sick bay. Then they were flown to the Norwegian hospital in Edinburgh. In London, the Navy had received the reconnaissance reports. These reports, with messages from Fritham Force, convinced them to send more help. The Navy needed to know if there was a clear path through the ice. This path would be from Bear Island to Spitsbergen and Jan Mayen Island.

June 14–15

P-Peter took off at 8:55 a.m. It flew at 150 feet (46 m) to avoid German radar. It flew against a headwind. It took ten hours to reach Bear Island. The crew saw no ice until 40 nautical miles (74 km) north of the island. But drift ice further on made a convoy route north of Bear Island impossible. The Catalina reached Barentsburg at 9:03 p.m. Men were seen waving from a hut 0.5 miles (0.80 km) north of town. The bags were thrown out. The plane landed. It took Glen, Ross, and a Norwegian soldier on board. It took off to check the polar ice west of the island towards Jan Mayen. Ice was seen 25 nautical miles (46 km) short of the island. No convoy could sail through it. P-Peter landed in Iceland at 9:30 a.m.

The results of the ice reconnaissance were too secret to send by wireless. P-Peter took off for a six-hour flight to Sullom Voe. There, the results could be sent by telephone. Glen had been on Spitsbergen for six weeks. He was called to the Navy along with the Catalina pilot. They gave a report on Operation Fritham. It included details of the Fritham Force's situation. It also said if more help would achieve the mission's goals. It assessed German strength on the island. And it discussed if the German team would be replaced by an automatic weather station. The Navy decided to end Fritham. They would start Operation Gearbox instead. This was a Norwegian mission supplied by the navy. It would work with the PQ convoys.

Aftermath

Operation Gearbox

The ships Manchester and Eclipse brought Operation Gearbox. This meant 57 Norwegian soldiers to help Fritham Force. The ships arrived in Iceland on June 28. They left on June 30. They were meant to look like part of the escort for Convoy PQ 17. This was if a German submarine saw them near Jan Mayen Island. The ships then turned north. They approached Isfjorden from the west. They arrived on July 2.

The ships kept their engines running. The Norwegians and 116 tons of supplies were unloaded. This included short-wave radios, anti-aircraft guns, skis, and sledges. Cranes were pulled back from the quay. Boats were hidden. The supplies were camouflaged. By July 5, four Oerlikon guns and M2 Browning machine-guns were set up. On July 3, a plane was heard flying to and from Longyearbyen. A Junkers Ju 52 was seen later that day. On July 23, a German Ju 88 plane flew over Advent Bay. It was checking how much the Allies had interfered with the German automatic weather station. As the plane flew low and made a sharp turn, Niks Langbak, a gunner, shot down the bomber. The crew were buried. Code books were saved from the wreckage.