Order of battle at the Battle of Trafalgar facts for kids

The Battle of Trafalgar was a huge naval battle fought on October 21, 1805. It was a clash between the British fleet and the combined fleets of France and Spain. The British had 27 large warships called ships of the line, while the French and Spanish had 33.

Both sides arranged their ships in columns. The British ships sailed side-by-side in two columns, while the allied French and Spanish ships followed each other in a single line. Understanding how these sailing ships moved, especially with the wind, is key to understanding the battle. The wind direction was super important for how the ships could move and fight.

Even though there was a plan, real battles often change quickly. Ship commanders had to be ready to react to what was happening. The "sailing order" and "battle order" were just plans. Ships were given numbers in a column, like "Number 1" at the front. The battle order was about where each ship was supposed to be during the attack.

Admiral Nelson would change his fleet's order to fit the moment. Bad weather could make it hard for commanders to control their ships. Nelson's fleet wasn't always the same; ships joined or left for repairs. For example, HMS Superb was being fixed and couldn't join the battle in time. The number of sailors on each ship also changed. Modern historians have worked hard to figure out the exact numbers of ships and casualties (people killed or wounded), and their estimates are usually very close.

Contents

Understanding the Battle: How Sailing Ships Fought

How Wind and Sails Affect Ships

The combined French and Spanish fleet left Cadiz harbor and sailed south. They used the north-westerly wind, which pushed them along. This wind also created waves that hit the ships from the side, making them roll. This made it hard for their cannons to aim steadily. Ships had to stay in a certain order to avoid blocking each other's wind or crashing.

The same wind that pushed the French and Spanish south was bringing the British north. A ship's sail works like an airplane wing. It curves to create a sideways push, allowing the ship to sail even somewhat against the wind. A deep part of the ship called a keel stops it from sliding sideways. Sails work best when the wind hits them at certain angles. Sailors adjust the sails using ropes called "sheets" to catch the wind just right. This is called "close-hauled" sailing. If the sails aren't set correctly, they just flap around uselessly.

A ship with square sails couldn't sail directly into the wind or too close to it. If the wind came from the north, the closest it could sail was east-north-east or west-north-west. To change direction against the wind, a ship would "tack," zig-zagging back and forth. However, this was very slow and risky for large ships. The most common way to turn around was "wearing," which involved turning the ship away from the wind. This was less risky and faster for big warships.

Sailing directly with the wind behind the ship or directly on its side was also difficult. The sails wouldn't fill properly. The wind needed to come from a slight angle to make the sails work well. If the wind was too strong, sailors had to make the sails smaller, a process called "reefing." In a storm, ships had to sail either almost into the wind or with the wind directly behind them to avoid being hit sideways by huge waves, which could be very dangerous. The side of the ship facing the wind was called the "weather" side, and the side away from the wind was the "lee" side.

Wind was everything for a sailing ship. Without it, a ship couldn't move. While steamships have more freedom, sailing captains had to be very skilled at using the wind to get where they needed to go.

Nelson's Smart Battle Plan

Nelson's battle plan was written down in a special note to his captains. It was signed "Nelson and Bronte" and dated October 9, 1805, just 12 days before the battle. Nelson's fleet was waiting near Cadiz, a heavily defended Spanish harbor, for the French and Spanish fleets to leave. Nelson knew it was too dangerous to attack a harbor directly. He kept his fleet hidden, out of sight and reach.

Sailing ships were slow and depended on the wind and waves. To get the most firepower, a fleet of ships would usually line up side-by-side, facing the enemy. This is why big warships were called "ships-of-the-line." But setting up such a line could take too much time, and the enemy might escape. So, Nelson had a different idea.

To win decisively, Nelson planned to attack the enemy line directly as soon as he saw them. This wasn't the usual way to fight, but it wasn't completely new either. He had discussed this plan with one of his favorite captains, Richard Goodwin Keats, weeks earlier. The downside was that only the front ships of the attacking column could fight at first. Nelson's 27 ships would attack in two columns. If they broke through the enemy line, they could then fight the enemy ships one by one.

Nelson's main order was to "attack the enemy, and keep fighting until they are captured or destroyed." He told his captains that if their ships got separated in the chaos, the best thing to do was to pull up next to an enemy ship and fight it directly.

Once the enemy was spotted, the British fleet would form two columns. These columns would sail with the wind coming from one side, either the "weather" (upwind) column or the "lee" (downwind) column. Nelson would lead the weather column, and his second-in-command would lead the other. The second-in-command could act on his own. Nelson didn't know which side would be the weather side until they were close to the enemy.

Nelson thought that if they saw the enemy fleet upwind, it would be spread out. This would mean the front of the enemy line couldn't easily help the ships behind it. His column would either be able to reach the enemy or not. If not, they would have to turn around and try again, which would turn the battle into a chase.

If they could reach the enemy, they would turn towards the enemy column. The lee column would aim for the enemy's rear (back). They would try to break through at the 12th ship from the end. Meanwhile, Nelson's weather column would aim for the center of the enemy line. Nelson hoped to destroy the enemy's rear ships before their front ships could turn around and join the fight. They also hoped to capture the French commander, Pierre-Charles Villeneuve, who they thought would be in the center. If the enemy's front tried to rescue their ships, the British fleet would block them and defeat them too.

If the enemy fleet was seen downwind, off the starboard (right) side, the British would be in a very strong position. They could easily sail downwind to the enemy and attack wherever they wanted. Nelson believed the enemy line would be moving in a certain way, allowing his lee column to follow the same plan: turn to starboard and break through at the 12th ship from the end.

In the actual battle, the enemy did appear downwind. However, they were sailing in a different direction than Nelson expected. This meant Nelson's weather column ended up attacking their rear. But the direct attack on the center and the idea of having two columns still worked, leading to a great British victory.

How the Plan Met the Real Battle

The French and Spanish ships were stuck in Cadiz Harbor, protected by powerful cannons on shore. Nelson briefly considered using new rockets to set the enemy ships on fire in the harbor. But this was exactly what the French commander, Villeneuve, wanted! He thought the combined fire from shore and ships would be the best way to defeat Nelson. So, Villeneuve waited, hoping Nelson would attack rashly.

Nelson kept track of the enemy using a secret line of spy ships. The enemy only saw the first spy ship far away. That ship would send signals to another, and so on, all the way back to Nelson, wherever he was.

Meanwhile, Napoleon, the leader of France, was getting impatient. He couldn't wait forever to invade Britain. He had turned his attention to fighting on land in Austria and Italy. He ordered Villeneuve to sail out of Cadiz immediately and head for the Mediterranean Sea.

However, Napoleon wasn't an expert in naval matters. He thought a fleet of 40 large ships could leave port instantly. But it takes a very long time for so many ships to get out of a harbor, even in good weather. And they couldn't leave without favorable winds. If the winds were tricky, it would be even slower, and if the winds were against them, it would be impossible.

British Fleet at Trafalgar

The table below shows the British ships and their positions just before the battle. HMS Africa was a bit separated to the north because of the weather and a missed signal during the night. It was supposed to be near the back of the lee column. The other warships were split into two columns: the weather column (north) and the lee column (south). The enemy line had been sailing from north to south. But as the battle began, they turned around, hoping to attack Nelson. The order of British ships in the table shows their position at that moment. Before the fight, they were in a single line. After the battle started, ships moved to get the best firing positions.

The British fleet had 33 warships, with 27 of them being "ships of the line." Smaller ships and frigates (which had been watching Cadiz) helped the fleet by sending messages and towing damaged ships, but they didn't fight directly. After Nelson was killed, Collingwood took command and moved to a different ship because his own ship, the Royal Sovereign, was badly damaged.

| Ship | Type | Guns | Fleet | Const- ruction |

Commanded by | Crew Size | Casualties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Killed | Wounded | Total | % | |||||||

| Attacking the Head of the French-Spanish Fleet | ||||||||||

| Africa | 2-decker | 64 | Capt Henry Digby | 498 | 8 | 44 | 52 | 10% | ||

| Weather column | ||||||||||

| Victory | 3-decker | 104 | Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson † Capt Thomas Masterman Hardy |

821 nominal 850 |

57 | 102 | 159 | 19% | ||

| Téméraire | 3-decker | 98 | Capt Eliab Harvey | 718 nominal 750 |

47 | 76 | 123 | 17% | ||

| Neptune | 3-decker | 98 | Capt Thomas Francis Fremantle | 741 | 10 | 34 | 44 | 6% | ||

| Leviathan | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Henry William Bayntun | 623 | 4 | 22 | 26 | 4% | ||

| Conqueror | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Israel Pellew | 573 | 3 | 9 | 12 | 2% | ||

| Britannia | 3-decker | 100 | Rear-Admiral The Rt Hon. Earl of Northesk Capt Charles Bullen |

854 | 10 | 42 | 52 | 6% | ||

| Agamemnon | 2-decker | 64 | Capt Sir Edward Berry | 498 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 2% | ||

| Ajax | 2-decker | 74 | Lieut John Pilford (acting captain) | 702 | 2 | 10 | 12 | 2% | ||

| Orion | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Edward Codrington | 541 | 1 | 23 | 24 | 4% | ||

| Minotaur | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Charles John Moore Mansfield | 625 | 3 | 22 | 25 | 4% | ||

| Spartiate | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Sir Francis Laforey | 620 | 3 | 22 | 25 | 4% | ||

| Lee column | ||||||||||

| Royal Sovereign | 3-decker | 100 | Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood Capt Edward Rotheram |

826 | 47 | 94 | 141 | 17% | ||

| Belleisle. | 2-decker | 74 | Capt William Hargood | 728 | 33 | 94 | 127 | 17% | ||

| Mars | 2-decker | 74 | Capt George Duff † Lieut William Hennah |

615 | 27 | 71 | 98 | 16% | ||

| Tonnant | 2-decker | 80 | Capt Charles Tyler | 688 | 26 | 50 | 76 | 11% | ||

| Bellerophon | 2-decker | 74 | Capt John Cooke † Lieut William Pryce Cumby |

522 | 28 | 127 | 155 | 30% | ||

| Colossus | 2-decker | 74 | Capt James Nicoll Morris | 571 | 40 | 160 | 200 | 35% | ||

| Achille | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Richard King | 619 | 13 | 59 | 72 | 12% | ||

| Revenge | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Robert Moorsom | 598 | 28 | 51 | 79 | 13% | ||

| Polyphemus | 2-decker | 64 | Capt Robert Redmill | 484 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 1% | ||

| Swiftsure | 2-decker | 74 | Capt William Gordon Rutherfurd | 570 | 9 | 8 | 17 | 3% | ||

| Dreadnought | 3-decker | 98 | Capt John Conn | 725 | 7 | 26 | 33 | 5% | ||

| Defiance | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Philip Charles Durham | 577 | 17 | 53 | 70 | 12% | ||

| Thunderer | 2-decker | 74 | Lieut John Stockham (acting captain) | 611 | 4 | 12 | 16 | 3% | ||

| Defence | 2-decker | 74 | Capt George Hope | 599 | 7 | 29 | 36 | 6% | ||

| Prince | 3-decker | 98 | Capt Richard Grindall | 735 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Attached | ||||||||||

| Euryalus | Frigate | 36 | Capt Hon Henry Blackwood | 262 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Naiad | Frigate | 38 | Capt Thomas Dundas | 333 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Phoebe | Frigate | 36 | Capt Hon Thomas Bladen Capel | 256 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Sirius | Frigate | 36 | Capt William Prowse | 273 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Pickle | Schooner | 8 | Lieut John Richards La Penotière | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | ||

| Entreprenante | Cutter | 10 | Lieut Robert Benjamin Young | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | ||

French and Spanish Fleet at Trafalgar

Just before the battle, the French and Spanish ships had been sailing from north to south. After they turned around, the front of their line became the back. During the battle, their single line broke into many smaller groups and individual ships. The combined fleet had 40 vessels in total, with 18 French and 15 Spanish ships of the line.

| Ship | Type | Guns | Fleet | Const- ruction |

Commanded by | Crew Size | Casualties | Fate | Killed in wreck | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Killed | Wounded | Total | % | |||||||||

| Neptuno | 2-decker | 80 | Capt Don H. Cayetano Valdés y Flores | 800 | 37 | 47 | 84 | 11% | Captured 21 Oct Recaptured 23 Oct Foundered 23 Oct |

few | ||

| Scipion | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Charles Berrenger | 755 | 17 | 22 | 39 | 5% | Escaped Captured 4 Nov |

|||

| Rayo | 3-decker | 100 | Commodore Don Enrique MacDonnell | 830 | 4 | 14 | 18 | 2% | Escaped Surrendered 23 Oct (to HMS Donegal) Foundered 26 Oct |

many | ||

| Formidable | 2-decker | 80 | Rear-Admiral Pierre Dumanoir Le Pelley Capt Jean-Marie Letellier |

840 | 22 | 45 | 67 | 8% | Escaped Captured 4 Nov |

|||

| Duguay-Trouin | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Claude Touffet | 755 | 20 | 24 | 44 | 6% | Escaped Captured 4 Nov |

|||

| Mont Blanc | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Guillaume-Jean-Noël de Lavillegris | 755 | 20 | 20 | 40 | 5% | Escaped Captured 4 Nov |

|||

| San Francisco de Asis | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Don Luis Antonio Flórez | 657 | 5 | 12 | 17 | 3% | Escaped, wrecked 23 Oct | none | ||

| San Agustin | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Don Felipe Jado Cagigal | 711 | 181 | 201 | 382 | 54% | Captured 21 Oct Abandoned and burnt 28 Oct |

|||

| Héros | 2-decker | 74 | Cmdr Jean-Baptiste-Joseph-René Poulain (DOW) | 690 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 5% | Escaped | |||

| Nuestra Señora de la Santísima Trinidad | 4-decker | 136 | Rear-Admiral Báltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros Capt Don Francisco Javier de Uriarte y Borja |

1048 | 216 | 116 | 332 | 32% | Captured 21 Oct Foundered 23 Oct |

few | ||

| Bucentaure | 2-decker | 80 | Vice-Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve Capt Jean-Jacques Magendie |

888 | 197 | 85 | 282 | 32% | Captured 21 Oct Recaptured 23 Oct Wrecked 23 Oct |

400 on Indomptable |

||

| Neptune | 2-decker | 80 | Commodore Esprit-Tranquille Maistral | 888 | 15 | 39 | 54 | 6% | Escaped | |||

| Redoutable | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Jean Jacques Etienne Lucas | 643 (nominal 550-600) | 300 | 222 | 522 | 81% | Captured 21 Oct Foundered 23 Oct |

many 172 ? |

||

| San Leandro | 2-decker | 64 | Capt Don José Quevedo | 606 | 8 | 22 | 30 | 5% | Escaped | |||

| San Justo | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Don Miguel María Gastón de Iriarte | 694 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 1% | Escaped | |||

| Santa Ana | 3-decker | 112 | Vice-Admiral Ignacio María de Álava y Navarrete Capt Don José de Gardoqui |

1189 1053 nominal |

95 | 137 | 232 | 20% | Captured 21 Oct Recaptured 23 Oct |

|||

| Indomptable | 2-decker | 80 | Capt Jean Joseph Hubert † | 887 | 20 | 30 | 50 | 6% | Escaped Wrecked 24 Oct> |

657 | ||

| Fougueux | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Louis Alexis Baudoin † | 755 | 60 | 75 | 135 | 18% | Captured 21 Oct Wrecked 22 Oct |

502 (84% casualties) | ||

| Intrépide | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Louis-Antoine-Cyprien Infernet | 745 | 80 | 162 | 242 | 32% | Captured 21 Oct Evacuated, blown up 24 Oct |

|||

| Monarca | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Don Teodoro de Argumosa | 667 | 101 | 154 | 255 | 38% | Captured 21 Oct Burnt 26 Oct |

|||

| Pluton | 2-decker | 74 | Commodore Julien Cosmao-Kerjulien | 755 | 60 | 132 | 192 | 25% | Escaped | |||

| Bahama | 2-decker | 74 | Commodore Don Dionisio Alcalá Galiano † | 690 | 75 | 66 | 141 | 20% | Captured 21 Oct | |||

| Aigle | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Pierre-Paulin Gourrège † | 755 | 70 | 100 | 170 | 23% | Captured 21 Oct Wrecked 23 Oct |

330 | ||

| Montañés | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Don Francisco Alsedo y Bustamante | 715 | 20 | 29 | 49 | 7% | Escaped | |||

| Algésiras | 2-decker | 74 | Rear-Admiral Charles-René Magon de Médine † Cmdr Laurent Tourneur |

755 | 77 | 142 | 219 | 29% | Captured 21 Oct Recaptured 23 Oct |

|||

| Argonauta | 2-decker | 80 | Capt Don Antonio Pareja (WIA) | 798 | 100 | 203 | 303 | 38% | Captured, scuttled 21 Oct | |||

| Swiftsure | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Charles-Eusèbe Lhospitalier de la Villemadrin | 755 | 68 | 123 | 191 | 25% | Captured 21 Oct | |||

| Argonaute | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Jacques Épron-Desjardins | 755 | 55 | 132 | 187 | 25% | Escaped | |||

| San Ildefonso | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Don Jose Ramón de Vargas y Varáez | 716 | 34 | 148 | 182 | 25% | Captured 21 Oct | |||

| Achille | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Louis-Gabriel Deniéport † | 755 | 480 | ? | 480 | 64% | Surrendered, blew up 21 Oct | |||

| Principe de Asturias | 3-decker | 112 | Admiral Don Federico Carlos Gravina (DOW) Rear-admiral Don Antonio de Escaño Commodore Don Ángel Rafael de Hore |

1113 | 54 | 109 | 163 | 15% | Escaped | |||

| Berwick | 2-decker | 74 | Capt Jean-Gilles Filhol de Camas † | 755 | 75 | 125 | 200 | 26% | Captured 21 Oct Foundered 22 Oct |

622 | ||

| San Juan Nepomuceno | 2-decker | 74 | Commodore Don Cosmé Damián Churruca y Elorza † | 693 | 103 | 151 | 254 | 37% | Captured 21 Oct | |||

| Attached | ||||||||||||

| Cornélie | Frigate | 40 | Capt André-Jules-François de Martineng | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | Escaped | |||

| Hermione | Frigate | 40 | Capt Jean-Michel Mahé | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | Escaped | |||

| Hortense | Frigate | 40 | Capt Louis-Charles-Auguste Delamarre de Lamellerie | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | Escaped | |||

| Rhin | Frigate | 40 | Capt Michel Chesneau | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | Escaped | |||

| Thémis | Frigate | 40 | Capt Nicolas-Joseph-Pierre Jugan | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | Escaped | |||

| Furet | Brig | 18 | Lieut Pierre-Antoine-Toussaint Dumay | 130 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | Escaped | |||

| Argus | Brig | 16 | Lieut Yves-Francois Taillard | 110 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | Escaped | |||

Battle Casualties: Who Was Lost?

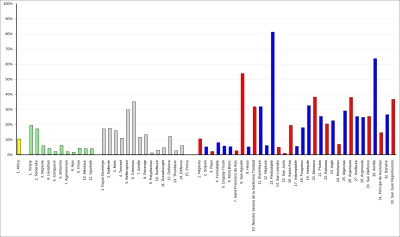

This section shows a graph of how many people were hurt or killed on each ship during the Battle of Trafalgar. Remember, these numbers are for the main battle on the first day. Casualties kept happening in the weeks after the battle, as storms hit and some captured enemy crews tried to take back their ships.

The graph shows three columns of ships and one separate ship (the Africa). The horizontal line shows the order of ships in their columns. The vertical line shows the percentage of crew members who were killed, wounded, or went missing and were presumed drowned. For example, on Nelson's ship, the Victory, about 19% of the crew were casualties.

Yellow = HMS Africa

Green = British Weather Column, led by Nelson

Grey = British Lee Column, led by Collingwood

The number is the order in the column.

Blue = French

Red = Spanish. The number is the order in the line. Data for this chart are from the above table.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |