Orphan Train facts for kids

The Orphan Train Movement was a special program that helped move children from busy cities in the Eastern United States. These children, often poor or without families, were sent to live with new families in the Midwest. This program ran from 1854 to 1929 and helped about 250,000 children find new homes.

The people who started the Orphan Train Movement said these children were orphans, abandoned, or homeless. But often, they were just children from poor immigrant families living in big cities. Some people criticized the program because families were not always checked properly. Also, there wasn't enough follow-up to see how the children were doing. Sadly, some children were treated unfairly, doing hard farm work without pay.

Three main groups worked to help these children: Children's Village, the Children's Aid Society, and later, the New York Foundling Hospital. These groups were supported by rich donors and had professional staff. They created a plan to place homeless children in foster homes across the country. These children traveled on trains called "orphan trains" or "baby trains." The program ended around 1930 because there was less need for farm workers in the Midwest.

Contents

- Why the Orphan Trains Started

- What "Orphan Train" Means

- The First Orphan Train Journey

- How Orphan Trains Worked

- How Many Children Were Placed?

- Challenges and Criticisms

- The End of the Orphan Train Movement

- What the Program Left Behind

- Organizations and Museums

- Forwarding Institutions

- Orphan Trains in Books and Movies

- Famous Orphan Train Riders

- See also

Why the Orphan Trains Started

Before the 1800s, if children lost their parents, relatives or neighbors usually took care of them. There weren't many orphanages.

Around 1830, the number of homeless children in big Eastern cities like New York City grew very quickly. By 1850, New York City had about 10,000 to 30,000 homeless children. At that time, the city's total population was only 500,000. Some children became orphans because their parents died from diseases like typhoid or the flu. Others were left alone because their families were very poor, sick, or had other problems. Many children sold small items like matches or newspapers to survive. To stay safe from street violence, they often formed groups or gangs.

In 1853, a young minister named Charles Loring Brace became worried about these street children. He started the Children's Aid Society. At first, the society offered boys religious guidance and taught them job skills and school subjects. Soon, they opened the Newsboys' Lodging House, a shelter where homeless boys could get cheap food and a place to sleep, plus a basic education. Brace and his team tried to find jobs and homes for children one by one. But there were too many children needing help. Brace then had the idea to send groups of children to rural areas for adoption.

Brace believed that street children would have better lives away from the poverty of New York City. He thought they would be better off with good farm families. He also knew that farmers needed workers. Brace believed farmers would welcome homeless children, treat them like their own, and help them grow up well. His program was an early form of what we now call foster care.

After a year of sending children one by one to farms in nearby states, the Children's Aid Society sent its first large group to the Midwest in September 1854.

What "Orphan Train" Means

The name "orphan train" was first used in 1854 to describe children traveling by train to new homes. However, this term wasn't widely used until much later, after the program had already ended.

The Children's Aid Society called its program the Emigration Department, then the Home-Finding Department, and finally, the Department of Foster Care. The New York Foundling Hospital later sent out what they called "baby" or "mercy" trains.

Most organizations and families used terms like "family placement" or "out-placement." The "out" part meant placing children outside of orphanages.

The term "orphan train" became very popular around 1978. This was when a TV show called The Orphan Trains aired. The term "orphan train" can be a bit confusing. Less than half of the children on these trains were actually orphans. About 25% of them had both parents still alive. Children with living parents ended up on the trains because their families were too poor to care for them, or because they had been abused, abandoned, or had run away. Many older boys and girls simply joined the program to find work or get a free ride out of the city.

The term "orphan trains" is also misleading because not all children traveled by train. Some didn't even go very far. The state that took in the most children (almost one-third) was New York itself. Nearby states like Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania also received many children. The decision about where to place a child often depended on where help was most available at that moment.

The First Orphan Train Journey

The first group of 45 children arrived in Dowagiac, Michigan, on October 1, 1854. The children had traveled for days in uncomfortable conditions. They were with E. P. Smith from the Children's Aid Society. Smith had even let two passengers on the riverboat adopt boys without checking them properly. He also added a boy he met at a train yard who claimed to be an orphan, but Smith never checked if it was true. At a meeting in Dowagiac, Smith spoke to the crowd, asking for sympathy for the children. He also pointed out that the boys could be useful on farms, and the girls could help with housework.

The Children's Aid Society later said that people wanting a child needed recommendations from their pastor and a judge. But it's likely this rule wasn't always followed strictly. By the end of that first day, fifteen boys and girls had found homes with local families. Five days later, twenty-two more children were adopted. Smith and the remaining eight children traveled to Chicago. Smith then put them on a train to Iowa City by themselves. There, a Reverend C. C. Townsend, who ran a local orphanage, took them in and tried to find them foster families. This first trip was seen as a big success. So, in January 1855, the society sent two more groups of homeless children to Pennsylvania.

How Orphan Trains Worked

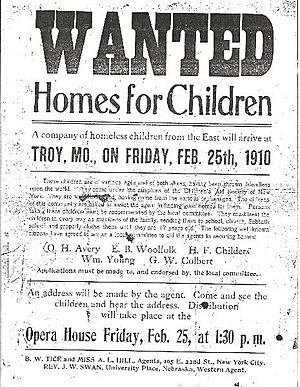

Local groups of important citizens were set up in towns where orphan trains stopped. These groups helped find a place for the adoptions to happen. They also told people about the event and arranged places for the orphan train group to stay. These local groups were also supposed to talk with the Children's Aid Society about whether families were suitable to take in children.

Brace's system relied on the kindness of strangers. Orphan train children were placed in homes for free. They were expected to help with chores around the farm. Families were supposed to raise them like their own children. This meant giving them good food and clothes, a basic education, and $100 when they turned twenty-one. Older children placed by the Children's Aid Society were supposed to be paid for their work. Legal adoption was not always required.

The Children's Aid Society had rules for placing boys. Boys under twelve were to be "treated as one of their own children" for school, clothes, and training. Boys aged twelve to fifteen were to "be sent to a school a part of each year." Representatives from the society were supposed to visit each family once a year to check on things. Children were also expected to write letters back to the society twice a year. However, there were only a few agents to check on thousands of children.

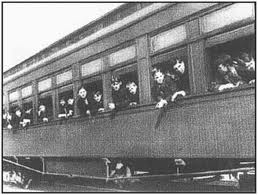

Before getting on the train, children were given new clothes and a Bible. Agents from the Children's Aid Society went with them. Few children understood what was happening at first. Once they did, some were happy to find a new family. Others felt angry or upset about being placed out when they had relatives back home.

Most children on the trains were white. Efforts were made to place children who didn't speak English with families who spoke their language. For example, Bill Landkamer, who spoke German, rode an orphan train several times in the 1920s. He was finally accepted by a German family in Nebraska.

Babies were the easiest to place. But it was always hard to find homes for children older than 14. People worried they were too set in their ways or had bad habits. Children with physical or mental disabilities or those who were sick were also hard to place. Many brothers and sisters were sent out together on orphan trains. But new parents could choose to take just one child, which often separated siblings.

Many orphan train children went to live with families who had asked for a child of a certain age, gender, or even hair and eye color. Others were led from the train station to a local theater. There, they were put on a stage, which is where the phrase "up for adoption" may have come from. An exhibit from the National Orphan Train Complex says the children "took turns giving their names, singing a little ditty, or 'saying a piece.'" According to Sara Jane Richter, a history professor, the children often had unpleasant experiences. "People came along and prodded them, and looked, and felt, and saw how many teeth they had."

Newspaper stories described the scene, sometimes like an auction. The Daily Independent of Grand Island, NE reported in May 1912: "Some ordered boys, others girls, some preferred light babies, others dark, and the orders were filled out properly and every new parent was delighted. They were very healthy tots and as pretty as anyone ever laid eyes on."

Brace raised money for the program by writing and giving speeches. Rich people sometimes paid for whole trainloads of children. Charlotte Augusta Gibbs, wife of John Jacob Astor III, had sent 1,113 children west by 1884. Railroads also gave discounts for the children and the agents traveling with them.

How Many Children Were Placed?

The Children's Aid Society sent about 3,000 children by train each year from 1855 to 1875. Orphan trains went to 45 states, and even to Canada and Mexico. In the early years, Indiana received the most children. At first, children were not sent to Southern states because Brace was against slavery.

By the 1870s, other groups like the New York Foundling Hospital and the New England Home for Little Wanderers in Boston also started their own orphan train programs.

New York Foundling Hospital's "Mercy Trains"

The New York Foundling Hospital was started in 1869 by Sister Mary Irene Fitzgibbon. It was a place for abandoned babies. The Sisters worked with Priests in the Midwest and South to place these children with Catholic families. From 1875 to 1914, the Foundling Hospital sent babies and toddlers to Catholic homes that had been arranged beforehand. Church members in these areas were asked to take children, and priests gave applications to approved families. This practice was first called the "Baby Train," and later the "Mercy Train." By the 1910s, 1,000 children a year were placed with new families.

Challenges and Criticisms

Linda McCaffery, a professor, explained that experiences on the Orphan Trains varied a lot. She said, "Many were used as strictly slave farm labor, but there are stories, wonderful stories of children ending up in fine families that loved them, cherished them, [and] educated them."

Orphan train children faced many difficulties. Some were teased by classmates for being "train children." Others felt like outsiders in their new families their whole lives. Many people in rural areas looked at the orphan train children with suspicion. They thought these children were troublemakers from the cities.

People criticized the orphan train movement for several reasons. They worried that children were placed too quickly, without proper checks on the families. They also felt there wasn't enough follow-up to see how the children were doing. Charities were also criticized for not keeping good records of the children they placed. In 1883, Brace agreed to an independent review. It found that local committees were not good at checking foster parents. The supervision was not strict enough. Many older boys had run away. But the overall conclusion was positive. Most children under fourteen were living good lives.

People applying for children were supposed to be checked by local business owners, ministers, or doctors. But these checks were rarely very thorough. Leaders in small towns often didn't want to reject a possible foster parent if that person was a friend or customer.

Many children lost their true identity. Their names were sometimes changed, and they moved many times. In 1996, Alice Ayler said, "I was one of the luckier ones because I know my heritage. They took away the identity of the younger riders by not allowing contact with the past."

Many children placed in the West had survived on the streets of big Eastern cities. They were often not the obedient children many families expected. In 1880, a Mr. Coffin from Indiana wrote that "Children so thrown out from the cities are a source of much corruption in the country places where they are thrown... Very few such children are useful."

Some places complained that orphan trains were just "dumping" unwanted children from the East into Western communities. In 1874, a national group charged that these practices led to higher costs for prisons in the West.

Older boys wanted to be paid for their work. Sometimes they asked for more money or left a placement to find a better-paying job. It's thought that young men caused 80% of the placement changes.

One of the many children who rode the train was Lee Nailing. Lee's mother died of sickness. After her death, Lee's father could not afford to keep his children. Another orphan train child was Alice Ayler. Alice rode the train because her single mother could not provide for her children. Before the journey, they lived off "berries" and "green water."

Catholic leaders said that some charities were purposely placing Catholic children in Protestant homes. They believed this was done to change the children's religious beliefs. The Society for the Protection of Destitute Roman Catholic Children in the City of New York was founded in 1863. This group ran orphanages and placement programs for Catholic youth to respond to Brace's Protestant-focused program. Similar concerns were raised about Jewish children being placed in non-Jewish homes.

Not all orphan train children were truly orphans. Some were made into orphans by being taken from their birth families and placed in other states. Some people claimed this was a plan to break up immigrant Catholic families. Some people who were against slavery also opposed placing children with Western families. They saw the system of children working without pay as a form of slavery.

Orphan trains also faced lawsuits. Parents sometimes sued to get their children back. Sometimes, a receiving parent or family member sued, claiming they had lost money or been harmed by the placement.

A complicated lawsuit happened in 1904 in the Arizona Territory. The New York Foundling Hospital sent 40 white children, aged 18 months to 5 years, to be placed with Catholic families. The families approved by the local priest were identified as "Mexican Indian." The nuns with the children didn't know about the tension between local white and Mexican groups. They placed white children with Mexican Indian families. A group of white men forcibly took the children from these homes. Most were then placed with white families. Some children were sent back to the Foundling Hospital, but 19 stayed with the white Arizona families. The Foundling Hospital tried to get these children back through a legal process. The Arizona Supreme Court decided it was best for the children to stay in their new Arizona homes. The U.S. Supreme Court later said that this type of legal action was not the right way to get children back. These events were widely reported in newspapers, with headlines like "Babies Sold Like Sheep."

The End of the Orphan Train Movement

As the Western United States became more settled, there was less demand for children to adopt. Also, Midwestern cities like Chicago and St. Louis started having their own problems with neglected children. These cities began to find ways to care for their own children in need.

In 1895, Michigan passed a law that made it harder to place children from out-of-state. Other states like Indiana and Kansas passed similar laws. These laws often required a large payment to ensure children placed in the state would not become a public burden. Agreements were made between New York charities and several Western states to continue placing children. But in 1929, these agreements ended and were not renewed. Charities were also changing how they supported children.

Finally, the need for the orphan train movement decreased because new laws were passed to help families in their own homes. Charities began to create programs to support poor and needy families. This meant fewer children needed to be placed away from their homes.

What the Program Left Behind

Between 1854 and 1929, about 200,000 American children traveled west by train to find new homes.

The Children's Aid Society considered its placed children successful if they became "creditable members of society." Reports often showed success stories. A survey in 1910 found that 87% of the children sent to country homes had "done well." Only 8% had returned to New York, and 5% had died, disappeared, or been arrested.

Brace's idea that children are better cared for by families than in institutions is a main belief of today's foster care system.

Organizations and Museums

The Orphan Train Heritage Society of America, Inc. was started in 1986 in Springdale, AR. It works to keep the history of the orphan train era alive. The National Orphan Train Complex in Concordia, KS is a museum and research center. It focuses on the Orphan Train Movement, the groups involved, and the children and agents who rode the trains. The museum is in the restored Union Pacific Railroad Depot in Concordia, which is a historic site. The Complex has many stories from riders and a research area. It helps people research riders, offers educational materials, and has photos and other items.

The Louisiana Orphan Train Museum opened in 2009. It is in a restored train depot in Opelousas, Louisiana. The museum has original papers, clothes, and photos of orphan train riders as children and adults. It especially looks at how the riders fit into the South Louisiana community. Most of them were legally adopted into their foster families. The museum is also home to the Louisiana Orphan Train Society. This society was founded in 1990. It runs the museum with volunteers, shares history, researches rider stories, and hosts a big yearly event like a family reunion.

Forwarding Institutions

Some of the children who took the trains came from these institutions (this is only a partial list):

- Angel Guardian Home

- Association for Befriending Children & Young Girls

- Association for Benefit of Colored Orphans

- Baby Fold

- Baptist Children's Home of Long Island

- Bedford Maternity, Inc.

- Bellevue Hospital

- Bensonhurst Maternity

- Berachah Orphanage

- Berkshire Farm for boys

- Berwind Maternity Clinic

- Beth Israel Hospital

- Bethany Samaritan Society

- Bethlehem Lutheran Children's Home

- Booth Memorial Hospital

- Borough Park Maternity Hospital

- Brace Memorial Newsboys House

- Bronx Maternity Hospital

- Brooklyn Benevolent Society

- Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum

- Brooklyn Home for Children

- Brooklyn Hospital

- Brooklyn Industrial school

- Brooklyn Maternity Hospital

- Brooklyn Nursery & Infants Hospital

- Brookwood Child Care

- Catholic Child Care Society

- Catholic Committee for Refugees

- Catholic Guardian Society

- Catholic Home Bureau

- Child Welfare League of America

- Children's Aid Society

- Children's Haven

- Children's Village, Inc.

- Church Mission of Help

- Colored Orphan Asylum

- Convent of Mercy

- Dana House

- Door of Hope

- Duval College for Infant Children

- Edenwald School for Boys

- Erlanger Home

- Euphrasian Residence

- Family Reception Center

- Fellowship House for boys

- Ferguson House

- Five Points House of Industry

- Florence Crittendon League

- Goodhue Home

- Grace Hospital

- Graham Windham Services

- Greer-Woodycrest Children's Services

- Guardian Angel Home

- Guild of the Infant Savior

- Hale House for Infants, Inc.

- Half-Orphan Asylum

- Harman Home for Children

- Heartsease Home

- Hebrew Orphan Asylum

- Hebrew Sheltering Guardian Society

- Holy Angels' School

- Home for Destitute Children

- Home for Destitute Children of Seamen

- Home for Friendless Women and Children

- Hopewell Society of Brooklyn

- House of the Good Shepherd

- House of Mercy

- House of Refuge

- Howard Mission & Home for Little Wanderers

- Infant Asylum

- Infants' Home of Brooklyn

- Institution of Mercy

- Jewish Board of Guardians

- Jewish Protector & Aid Society

- Kallman Home for Children

- Little Flower Children's Services

- Maternity Center Association

- McCloskey School & Home

- McMahon Memorial Shelter

- Mercy Orphanage

- Messiah Home for Children

- Methodist Child Welfare Society

- Misericordia Hospital

- Mission of the Immaculate Virgin

- Morrisania City Hospital

- Mother Theodore's Memorial Girls' Home

- Mothers & Babies Hospital

- Mount Siani Hospital

- New York Foundling Hospital

- New York Home for Friendless Boys

- New York House of Refuge

- New York Juvenile Asylum (Children's Village)

- New York Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children

- Ninth St. Day Nursery & Orphans' Home

- Orphan Asylum Society of the City of Brooklyn

- Orphan House

- Ottilie Home for Children

Orphan Trains in Books and Movies

- Big Brother by Annie Fellow-Johnson, a children's book from 1893.

- Extra! Extra! The Orphan Trains and Newsboys of New York by Renée Wendinger, a nonfiction book with pictures about the orphan trains. ISBN: 978-0-615-29755-2

- Good Boy (Little Orphan at the Train), a painting by Norman Rockwell.

- "Eddie Rode The Orphan Train", a song by Jim Roll, also sung by Jason Ringenberg.

- Last Train Home: An Orphan Train Story, a historical story from 2014 by Renée Wendinger. ISBN: 978-0-9913603-1-4

- Orphan Train, a 1979 TV movie directed by William A. Graham.

- "Rider on an Orphan Train", a song by David Massengill from his 1995 album The Return.

- Orphan Train, a 2013 novel by Christina Baker Kline.

- Placing Out, a 2007 documentary film.

- Toy Story 3, a 2010 Pixar animated film that briefly mentions "Orphan Train." The idea of foster families is a common theme in the Toy Story movies.

- "Orphan Train", a song by U. Utah Phillips released in 2005.

- Swamplandia!, a novel by Karen Russell, where a character was on an Orphan Train.

- Lost Children Archive, a novel by Valeria Luiselli, which talks about the forced movement of groups of people, including the Orphan Trains.

- The Copper Children, a play by Karen Zacarías that started in 2020.

- My Heart Remembers, a 2008 novel by Kim Vogel Sawyer, about siblings separated on an orphan train.

- "Orphan Train Series" by Jody Hedlund, a series about three orphaned sisters in the 1850s and the New York Children's Aid Society.

- 0.5 An Awakened Heart (2017)

- 1. With You Always (2017)

- 2. Together Forever (2018)

- 3. Searching for You (2018)

- ’’ Orphan Train, episode 16, season 2 of Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman

Famous Orphan Train Riders

- Eden Ahbez (songwriter of "Nature Boy")

- Joe Aillet

- John Green Brady

- Andrew H. Burke

- Henry L. Jost

- Marion Parnell Costello Perry

- Frank Raymond Elliott

See also

In Spanish: Orphan Train para niños

In Spanish: Orphan Train para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |