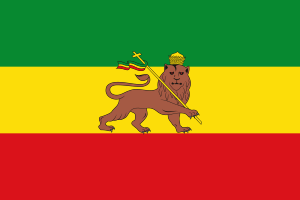

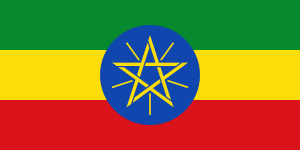

Pan-Ethiopian nationalism facts for kids

Ethiopian nationalism (called Ītyop'iyawīnet in Amharic) is the idea that people from Ethiopia are one big nation. It celebrates the shared culture of Ethiopians. This idea also says that all the different ethnic groups in Ethiopia should have equal rights and be part of the country's power. Ethiopian nationalism is a type of civic nationalism. This means it includes many different ethnic groups and encourages diversity.

People who support Ethiopian nationalism believe it is different from, and against, ideas that favor one ethnic group over others. They say that some government policies have divided regions based on ethnicity. This has sometimes caused people to move from their homes. However, there has been some disagreement with multi-ethnic Ethiopian nationalism. This is because of tensions between groups like the Amhara, Oromo, Somali, and Tigray peoples. Some of these groups have wanted to form their own separate countries. This also happened when Eritrea became independent from Ethiopia.

Contents

A Look at Ethiopia's History

The idea of an Ethiopian nation is thought to have started with the Kingdom of Aksum around 300 AD. The Aksumite Kingdom was mostly Christian. At its strongest, it controlled parts of modern-day Ethiopia, Eritrea, and coastal areas of Southern Arabia. This kingdom helped develop the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

However, when Islam spread in the 600s, the Aksumite Kingdom began to decline. Many people in the lowlands became Muslim, while those in the highlands stayed Christian. This created religious and tribal tensions. The Aksumite society then became a group of smaller city-states. They still kept the Aksum language.

After the Aksumite Kingdom weakened, its power moved south. The capital was moved to a new place. Even though the kingdom lost land in the north, it gained land in the south. Ethiopia was no longer a big economic power, but Arab traders still visited.

Around the 900s, during the rule of Degna Djan, the empire continued to grow south. It sent troops into the Kaffa region and spread Christianity in other areas.

Local stories say that around 960, a Jewish Queen named Yodit (or "Gudit") defeated the empire. She is said to have burned churches and books. While there is proof of churches being burned and an invasion around this time, some historians question if she really existed. Another idea is that a pagan queen from the south ended Aksumite power. It is clear that a female ruler did take over the country around this time. Her rule ended before 1003.

After a short "Dark Age," the Zagwe dynasty took over in the 11th or 12th century. This new kingdom was smaller. However, Yekuno Amlak, who started the modern Solomonic dynasty around 1270, said he was a descendant of the last Aksum emperor. This showed a link to the old kingdom. The culture and traditions of Aksum also continued. For example, the buildings of the Zagwe dynasty in Lalibela still show strong Aksumite influence.

In the mid-1500s, armies from the Adal Sultanate, led by Ahmed Gragn, invaded the Ethiopian Highlands. This event is known as the "Conquest of Habasha." After these invasions, Ethiopia lost its southern parts. Groups like the Gurage people were cut off from the rest of the country. In the late 1500s, the nomadic Oromo people moved into the Abyssinian plains. They took over large areas during the Oromo migrations.

Ethiopian leaders often fought each other for control. The Amhara people seemed to gain power when Yekuno Amlak took the throne in 1270. He defeated the Agaw lords of Lasta.

The Gondarian dynasty, which had been the center of royal power since the 1500s, lost its influence. This happened after Iyasu the Great was killed. This led to a period called Zemene Mesafint ("Era of the Princes"). During this time, different warlords fought for power. The emperors became like figureheads, with little real power. This era ended when a young man named Kassa Haile Giorgis, later known as Emperor Tewodros, defeated his rivals and became emperor in 1855.

The Tigrayans briefly returned to power with Yohannes IV in 1872. After his death in 1889, power shifted back to the Amharic-speaking elite. His successor, Menelik II, was of Amhara origin. In 1935, the League of Nations reported that after Menelik's forces invaded non-Abyssinian lands, the people there were enslaved and heavily taxed. This led to a decrease in population.

Some experts believe the Amhara people were Ethiopia's ruling group for centuries. This includes the line of emperors ending with Haile Selassie I. However, other scholars disagree. They say that other ethnic groups have always been involved in the country's politics. This confusion might come from calling all Amharic-speakers "Amhara," even if they were from different ethnic groups. Also, many people from other groups adopted Amharic names. It is also said that most Ethiopians can trace their family history to many ethnic groups. For example, Emperor Haile Selassie I and his Empress Menen Asfaw had both Amhara and Oromo family lines.

The Oromo migrations involved a large group of people moving from the southeastern parts of the empire. A monk named Abba Bahrey wrote about this at the time. After these migrations, the empire's organization changed. Faraway provinces became more independent.

By 1607, Oromos were also important in imperial politics. This happened when Susenyos I, who was raised by an Oromo clan, took power. He was helped by Oromo generals.

The rule of Iyasu I the Great (1682-1706) was a time of great strength for the empire. He sent ambassadors to France and Dutch India. During the rule of Iyasu II (1730-1755), the empire was strong enough to fight a war against the Sennar Sultanate.

The Wallo and Yejju clans of the Oromo people became very powerful in 1755. This was when Emperor Iyoas I became emperor in Gondar. These groups became major players during the Zemene Mesafint period, which started in 1769.

Modern Ethiopia was formed under the leadership of the Shawan people, who included both Amharas and Oromos. Important emperors were Tewodros II (1855-1868), Yohannes IV from Tigray (1869-1889), and Menelik II (1889-1913). Menelik II famously pushed back an Italian invasion in 1896.

From 1874 to 1876, the Empire, under Yohannes IV, won the Ethiopian-Egyptian War. They decisively beat the invading forces at the Battle of Gundet. In 1887, Menelik, the king of Shewa, invaded the Emirate of Harar after his victory at the Battle of Chelenqo.

Starting in the 1890s, under Menelik II, the empire's forces expanded. They took control of lands to the west, east, and south. These new areas included lands of the Western Oromo, Sidama, Gurage, Wolayta, and Dizi peoples. The new territories created the modern borders of Ethiopia.

Unlike most of Africa, Ethiopia was never fully colonized. It was accepted as the first independent African-governed state in the League of Nations in 1922. Ethiopia was occupied by Italy after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, but it was freed by the Allies during World War II.

After the war, Ethiopia took control of Eritrea. However, tensions grew between the Amhara and the different ethnic groups in Eritrea. There were also tensions with Oromo, Somali, and Tigray peoples within Ethiopia. Many of these groups wanted to separate from Ethiopia. After the Ethiopian monarchy was overthrown by a military government called the Derg, the country became allies with the Soviet Union and Cuba. This happened after the United States did not support Ethiopia in its fight against Somali separatists. After the military government ended in 1993, Eritrea became a separate country from Ethiopia.

The Meaning of Independence

In March 1896, a very important battle happened between Italian colonial forces and the Ethiopian Empire. This was the Battle of Adwa in northern Ethiopia. The battle was short but very violent, with many lives lost. Emperor Menelik II brought together all Ethiopians, no matter their background, to fight. Millions of Ethiopian citizens marched to protect their African Empire. Ethiopia won this battle, which gave the country a special history of staying independent against European powers.

The Battle of Adwa is a key event for Ethiopian nationalism. For many Ethiopians, the idea of a foreign invasion makes them feel very patriotic. When the Battle of Adwa happened, most of Africa was controlled by European countries. Ethiopia's independence showed that European power was not unbeatable. It gave hope to black nations and people around the world. For many Ethiopians, this moment showed the nation's true purpose.

While the first war against Italy united the country, the 1934 invasion by Benito Mussolini was very divisive. Some historians say the 1934 Italo-Abyssinian war was also like a civil war. This is because political differences within Ethiopia became even bigger during the invasion. This led to a time of strong disagreements that shaped Ethiopian politics after the war.

The Era of Ethnic Federalism

Since 1992, before Abiy Ahmed became Prime Minister, the TPLF had a lot of control over the government. They used their power to bring wealth and development mainly to the Tigray Region. This strong rule by the Tigray people was partly a reaction to the power the Amharas had in media and government. When a few ethnic groups, or even just one, control everything, it can make other groups feel left out. This has sometimes led to violence.

In the early 1990s, the TPLF believed that dividing the country into regions based on ethnicity (called ethnic federalism) would help. They thought it would:

- Reduce fighting between ethnic groups.

- Make sure all areas of the country had fair resources.

- Make government services work better.

They believed this system could achieve these goals without harming economic growth or political stability.

Even though these regions did not have full control over laws or taxes, their creation gave more importance to different independence and ethnic nationalist movements. For Ethiopian Nationalists, this system has made different groups stronger. However, it has also weakened national unity and the idea of Pan-Ethiopianism (unity of all Ethiopians). The increased freedom for these groups, combined with more control by Tigray leaders, created a difficult situation. The ruling group was giving power to ethnic groups but also stopping their political wishes.

For example, after the 2005 elections, the TPLF used force to stop people who disagreed with them. This only made ethnic groups more extreme and increased divisions. Many Ethiopian nationalists believe that ethnic federalism has made politics in Ethiopia a "zero-sum game." This means that for one group to win power, other groups must lose significant power. By pushing aside the idea of a multi-ethnic Ethiopian identity, the TPLF has made ethnic differences stronger. This has created a system where ethnic groups are most important, not political ideas.

In 2015, a plan to expand the capital city, Addis Ababa, into the Oromia area was announced. Thousands of Oromo Youth Liberation Movement Members protested. They demanded more political representation, an end to the plan, and ways to express their disagreement. The ruling party tried to stop these protests with force, but they only grew. Amharas, who were angry about not getting back some of their lands, also joined the protests. These protests, mostly by Oromos and Amharas, demanded fair political representation and influence.

After a 10-month state of emergency, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn resigned. Abiy Ahmed was chosen as the next prime minister. He has mixed Oromo-Amhara family roots, with a preference for his Oromo identity. Since becoming prime minister, he has made big changes. He has allowed political opponents to return, released some political prisoners, and made the economy more open. While his efforts to reform and make the country more democratic have gained support, he has not yet fully addressed the problems of the ethnic federalist system. Many Pan-Ethiopians believe this system is the main cause of ethnic politics and tensions. Ethiopian nationalists think that ethnic federalism must end. They believe this will shift Ethiopian politics from favoring ethnic groups to focusing on ideas. They also think it will create national unity and reduce loyalty to specific ethnic groups, leading to a time of unity and success.

See also

- Ethiopianism