Parachuting facts for kids

Four skydivers with deployed parachutes in Bex, Switzerland

|

|

| Highest governing body | Fédération Aéronautique Internationale |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Mixed-sex | Yes |

| Type | Air sports |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | No |

| World Games | 1997 – 2017 |

Parachuting is an exciting sport and fun activity. It involves jumping from an aircraft, like a plane, and using a parachute to float safely back to the ground. Many people think of it as an extreme sport because it involves some risks.

Contents

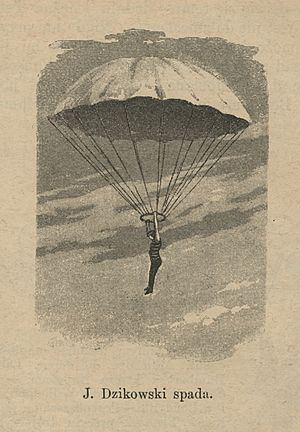

The History of Parachuting

The very first parachute jump was made by André-Jacques Garnerin on October 22, 1797. He invented the parachute and jumped from a hot air balloon about 3,200 feet above Paris! His parachute looked very different from today's parachutes.

Later, in 1919, Leslie L. Irvin made the first planned free-fall jump. This was a big step because his parachute had a "ripcord" that he could pull to open it. Before this, in 1914, a woman named Tiny Broadwick had an unplanned free-fall when her parachute line got stuck. She had to cut it and open her parachute by hand to get free.

Over time, the military started using parachutes. They used them to help pilots escape from damaged aircraft. Later, they used parachutes to drop soldiers into battle zones. Parachuting became an international sport in 1952.

What is Parachuting Used For?

Parachuting is a popular hobby and a competitive sport. In 2018, people made 3.3 million jumps in the United States alone!

Militaries around the world use parachuting to deploy soldiers and supplies. Special forces often use free-fall parachuting to enter areas quietly. Some forest firefighters, called "smokejumpers" in the United States, even parachute into remote areas to fight forest fires.

In the past, pilots and passengers sometimes used parachutes to escape from aircraft that were in trouble. This was common during World War I and World War II. Today, it's less common because modern planes often have ejection seats for emergencies.

Staying Safe While Skydiving

Safety is very important in skydiving. In many places, like the U.S., skydivers must wear two parachutes: a main parachute and a reserve (backup) parachute. A certified expert called a "parachute rigger" regularly checks and repacks the reserve parachute.

Many skydivers also use an automatic activation device (AAD). This device is like a small computer that opens the reserve parachute automatically if it senses the skydiver is still falling too fast at a certain low height. Some countries even require AADs for new jumpers. Skydivers also use altimeters (devices that show their height) to know when to open their parachutes.

Risks in Skydiving

Most injuries or accidents happen when a skydiver makes a mistake while steering their parachute. This can lead to landing too fast.

Changing wind conditions can also be risky. Strong winds or sudden changes in wind direction can make landings harder and more dangerous.

Sometimes, two or more skydivers under open parachutes can collide. This is called a "canopy collision." If parachutes get tangled, they might collapse. Skydivers then have to quickly release their main parachute and open their reserve. This is very dangerous if it happens too close to the ground.

Equipment can also fail, but this is rare. Only about 1 in 750 main parachute deployments have a problem.

Some types of parachuting, like BASE jumping (jumping from buildings, antennas, spans, or earth), are much riskier. These are usually only done by very experienced jumpers.

Most places require skydivers to be at least 18 years old.

Weather and Visibility

Skydiving in bad weather, like thunderstorms or strong winds, is very dangerous. Good skydiving centers will stop jumps when the weather is poor. It's also usually against the rules to jump through clouds, as skydivers need to see clearly to avoid other aircraft.

Learning to Skydive

You can even practice skydiving without jumping from a plane! Vertical wind tunnels let you experience freefall indoors, and virtual reality simulators help you learn to control a parachute.

When you're ready to jump, there are different ways to learn:

- Static line: A rope attached to the plane opens your parachute automatically as you jump.

- Instructor-assisted deployment: An instructor helps you deploy your parachute.

- Accelerated free fall: Two instructors hold onto you during freefall, teaching you how to control your body.

- Tandem skydiving: You are strapped to an experienced instructor who handles everything. This is a popular first jump!

How a Parachute Opens

When a skydiver reaches the right height, they pull a small handle. This releases a tiny parachute called a "pilot-chute." The pilot-chute catches the air and pulls out a bag containing the main parachute.

The main parachute unfolds slowly. A special piece of fabric called a "slider" helps control how fast the parachute opens. This prevents the parachute from opening too quickly, which could damage it or hurt the skydiver. As the parachute opens, the skydiver slows down a lot, from about 190 miles per hour to about 28 miles per hour.

If the main parachute doesn't open correctly, the skydiver can pull a "cut-away" handle. This releases the main parachute. Then, they pull another handle to open the reserve parachute. Some systems have a special line that helps open the reserve parachute even faster.

Skydiving Competitions

Skydivers compete in many different events, both indoors (in wind tunnels) and outdoors. World Championships are held every two years. Some popular events include:

Accuracy Landing

In "Classic Accuracy," skydivers try to land as close as possible to a small target, only 2 centimeters wide! They jump from about 3,300 to 4,000 feet and open their parachutes quickly. An electronic pad measures how close they land. The person with the lowest total score (meaning they landed closest to the target) wins. This sport is exciting to watch because the action happens very close to the ground.

Canopy Formation

This event, also called CREW, involves skydivers opening their parachutes soon after leaving the plane. They then fly very close to each other to create different shapes and formations. They often "dock" by putting their feet into another person's parachute lines. Because they are so close, skydivers carry a special knife in case they get tangled.

Formation Skydiving

Formation Skydiving (FS) started in California in the 1960s. In this event, skydivers link up with each other in freefall to create different formations. The goal is to build specific shapes as quickly and cleanly as possible before opening their parachutes.

Style

Style is like the sprint of parachuting. It's an individual event done in freefall. Skydivers try to gain as much speed as possible (over 250 miles per hour!) and then perform a series of turns and flips very quickly and smoothly. Their jumps are filmed from the ground, and judges score their performance based on speed and accuracy.

Drop Zones

A "drop zone" (or DZ) is the area where skydivers jump and land. It's usually located next to a small airport. A drop zone is also the name for the entire skydiving business, including the staff like instructors, pilots, and people who pack parachutes.

Skydiving Equipment

A skydiver's main equipment includes:

- A container/harness system (the backpack that holds the parachutes)

- A main parachute

- A reserve (backup) parachute

- Often, an automatic activation device (AAD)

Other important items are a helmet, goggles, a jumpsuit, an altimeter (to check height), and gloves. Many skydivers also wear cameras, like GoPros, to record their jumps.

Skydiving equipment can be expensive. A new container and harness might cost between $1,500 and $3,500. Main parachutes can be $2,000 to $3,600, and reserve parachutes cost $1,500 to $2,500. AADs are around $1,000. However, most equipment is built to last and can be used by several people before it needs to be replaced. Experts called riggers check the equipment to make sure it's safe.

Traveling with a Parachute

If you own a parachute and want to travel with it on a plane, it's best to carry it with you in the cabin if possible. This prevents it from being damaged in the baggage hold.

However, since most parachutes have an automatic activation device (AAD), which might contain small explosive parts or unusual metal pieces, going through airport security can be tricky. It's a good idea to tell the airline when you book your ticket that you're traveling with a parachute. You should also bring documents like:

- The AAD's explanation card, which shows what it looks like on an X-ray scanner.

- Documents from the airline or airport that say these devices are allowed.

- The parachute's instruction book, which explains all its parts.

These documents can help airport staff understand what's inside your parachute bag.

Amazing Parachute Jumps and Records

- In 1914, Tiny Broadwick made the first manual free-fall jump.

- In 1962, Eugene Andreev (from the USSR) set a record for the longest free-fall parachute jump. He fell for 24,500 meters (about 80,380 feet) from an altitude of 25,458 meters (about 83,523 feet). He did this without a special drogue chute to slow him down.

- In 1960, Captain Joseph Kittinger of the United States Air Force made a series of high-altitude jumps for research. His most famous jump was from 102,800 feet (about 19.5 miles up!). He fell for over 4 minutes, reaching speeds of 614 miles per hour, before opening his parachute at 14,000 feet. He set many records that day.

- In 2012, Felix Baumgartner broke Kittinger's records. He jumped from 128,100 feet (about 24 miles up!) and became the first skydiver to break the speed of sound, reaching 833.9 miles per hour (Mach 1.24). Kittinger was even part of Baumgartner's mission control team!

- In 2014, Alan Eustace broke Baumgartner's record for the highest fall, jumping from 135,908 feet (about 25.7 miles up!).

Other Records

- Most Jumps: Don Kellner holds the record for the most parachute jumps, with 46,355 jumps by 2021!

- Most Jumps by a Woman: Cheryl Stearns (U.S.) has made 20,000 jumps. She also made 352 jumps in just 24 hours!

- Youngest Skydiver: Erin Hogan was the world's youngest skydiver in 2002, doing a tandem jump at age 5. This record was broken in 2003 by a 4-year-old from New Zealand.

- Oldest Tandem Skydiver: Irene O'Shea made a tandem jump in Australia at 102 years old in 2018!

- Largest Free-Fall Formation: In 2006, 400 people linked together in freefall in Thailand.

- Largest Female-Only Formation: In 2009, 181 women from 26 countries jumped together to form a large shape.

- Largest Head-Down Formation: In 2015, 164 skydivers linked up while falling head-first towards the Earth.

- Oldest Civilian Parachute Club: The Irish Parachute Club, founded in 1956, is the oldest in the world.

Images for kids

-

Parachutists jumping from an Ilyushin Il-76 of the Ukraine Air Force (2014)

See also

In Spanish: Paracaidismo para niños

In Spanish: Paracaidismo para niños

- List of paratrooper forces

- Banzai skydiving

- Dolly Shepherd

- Parachute landing fall

- Paratrooper

- Space diving

- Speed skydiving

- Space Games

- The First School of Modern SkyFlying

- Skydiver day

- High-altitude military parachuting

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |