Jack Johnson (boxer) facts for kids

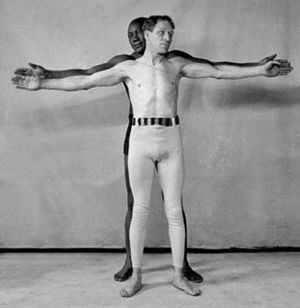

Quick facts for kids Jack Johnson |

|

|---|---|

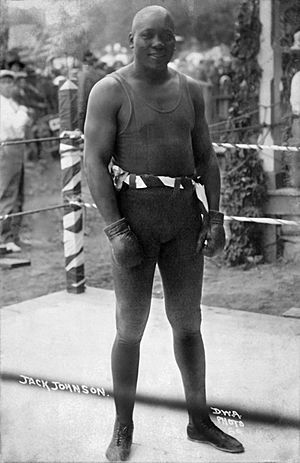

Johnson in 1915

|

|

| Statistics | |

| Nickname(s) | Galveston Giant |

| Rated at | Heavyweight |

| Height | 6 ft 1⁄2 in (184.2 cm) |

| Reach | 74 in (188 cm) |

| Born | March 31, 1878 Galveston, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | June 10, 1946 (aged 68) Franklinton, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 95 |

| Wins | 72 |

| Wins by KO | 38 |

| Losses | 11 |

| Draws | 11 |

| No contests | 3 |

John Arthur Johnson (born March 31, 1878 – died June 10, 1946), known as the "Galveston Giant", was an American boxer. He made history by becoming the first African-American world heavyweight boxing champion. This happened during a time when Jim Crow laws made life very unfair for black people in the United States.

Many people think Jack Johnson was one of the greatest boxers ever. His 1910 match against James J. Jeffries was called the "fight of the century." A filmmaker named Ken Burns said that for over 13 years, Jack Johnson was the most famous and talked-about African-American person in the world. He was important not just in boxing, but also in the history of racism in the United States.

In 1912, Johnson opened a fancy restaurant and nightclub in Chicago. It was special because it welcomed people of all races, which was very rare back then. Johnson was later arrested for supposedly breaking a law called the Mann Act. This law made it illegal to take women across state lines for certain reasons. Many believed these charges were unfair and happened because of his race and his marriages to white women. He was sentenced to a year in prison but left the country. He fought boxing matches overseas for seven years. In 1920, he returned to the U.S. and served his time in prison.

Johnson kept fighting in matches for money for many years. He also ran other businesses and had good deals to promote products. He died in a car crash on June 10, 1946, when he was 68 years old. He is buried in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago. On May 24, 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump officially pardoned Johnson. This meant his past conviction was forgiven.

Contents

Early Life and Boxing Start

Johnson was born on March 31, 1878. He was the third of nine children. His parents, Henry and Tina Johnson, had been enslaved. They worked as a janitor and a dishwasher. His father had also worked for the Union army during the Civil War.

Jack grew up in Galveston, Texas. He went to school for five years. When he was young, he was thin, but like his brothers and sisters, he was expected to work. Even though he grew up in the South, Johnson said that segregation wasn't a big problem in his part of Galveston. He remembered: "As I grew up, the white boys were my friends and my pals. I ate with them, played with them and slept at their homes. Their mothers gave me cookies, and I ate at their tables. No one ever taught me that white men were superior to me."

After leaving school, Johnson worked at the local docks. He tried other jobs too. One day, he went to Dallas and found work exercising horses at a race track. He stayed there until he became an apprentice to a carriage painter named Walter Lewis. Lewis liked watching his friends box, and Johnson started to learn how to fight. Johnson later said that Lewis was the reason he became a boxer.

When he was 16, Johnson moved to New York City. He lived with Barbados Joe Walcott, a boxer from the West Indies. Johnson again found work with horses but was fired for making a horse too tired. When he returned to Galveston, he got a job as a janitor at a gym. He saved enough money to buy boxing gloves and practiced whenever he could.

One time, Johnson was arrested for fighting a man named Davie Pearson. After they were both released from jail, they met at the docks. Johnson beat Pearson in front of a big crowd. He then fought in a summer boxing league against John "Must Have It" Lee. Because prize fighting was illegal in Texas, the fight moved to the beach. Johnson won his first fight and earned one dollar and fifty cents.

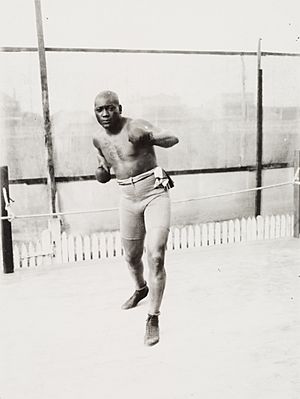

Boxing Career Highlights

Johnson started his professional boxing career on November 1, 1898, in Galveston. He won his first fight by knocking out Charley Brooks in the second round. In his third professional fight, he faced "Klondike" (John W. Haynes) in Chicago. Klondike was a black heavyweight boxer. Klondike won that fight, but Johnson beat him in a later rematch.

Learning from Joe Choynski

On February 25, 1901, Johnson fought Joe Choynski in Galveston. Choynski was a well-known and experienced heavyweight. He knocked out Johnson in the third round. Since prize fighting was illegal in Texas, both boxers were arrested. They couldn't afford the high bail. The sheriff let them go home at night if they agreed to practice boxing in their jail cell during the day. Many people came to watch them. After 23 days, their bail was lowered, and they were released. Johnson later said he learned a lot about boxing during his time in jail. He and Choynski became friends.

Johnson believed that Choynski's coaching helped him become a great boxer. Choynski saw Johnson's natural talent. He taught Johnson how to defend himself, telling him, "A man who can move like you should never have to take a punch."

Becoming a Top Boxer

Johnson continued to win fights. He beat former black heavyweight champion Frank Childs in 1902. By 1903, Johnson had won at least 50 fights against both white and black opponents.

World Colored Heavyweight Champion

Johnson won his first major title on February 3, 1903. He beat Denver Ed Martin to become the World Colored Heavyweight Champion. This title was for black boxers because they were often not allowed to fight for the main world heavyweight title. Johnson held this title for a long time, until he won the world heavyweight title in 1908. He defended the colored heavyweight title 17 times. He beat famous black boxers like Denver Ed Martin, Frank Childs, Sam McVey, and Sam Langford.

World Heavyweight Champion

Johnson really wanted to win the world heavyweight title. But the champion at the time, James J. Jeffries, refused to fight him because Johnson was black. Jeffries then retired. However, Johnson did fight former champion Bob Fitzsimmons in July 1907 and knocked him out quickly.

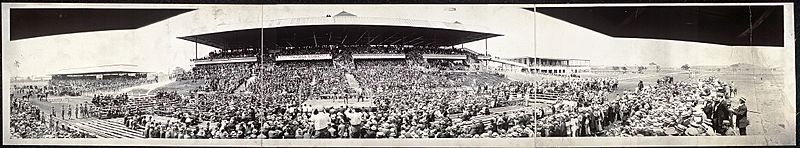

Johnson finally won the world heavyweight title on December 26, 1908. He beat the champion, Canadian Tommy Burns, in Sydney, Australia. Johnson had followed Burns around the world for two years, asking him for a match. Burns finally agreed to fight after promoters promised him a lot of money. The fight lasted 14 rounds before the police stopped it. Johnson was declared the winner in front of over 20,000 people.

After Johnson's victory, many white people were upset. Some, like writer Jack London, called for a "Great White Hope" to take the title from Johnson. The newspapers often wrote racist things about Johnson. The New York Times even wrote that if Johnson won, many black people would misunderstand his victory and think they were equal to white people. As champion, Johnson had to fight many boxers who were called "great white hopes." In 1909, he beat Tony Ross, Al Kaufman, and the middleweight champion Stanley Ketchel.

His fight with Ketchel was supposed to be a friendly exhibition. But in the 12th round, Ketchel hit Johnson hard, knocking him down. Johnson quickly got up, very annoyed. He immediately rushed at Ketchel and hit him with a powerful uppercut, a punch he was famous for. This punch knocked Ketchel out and even knocked out his front teeth. You can see Johnson removing them from his glove in old films of the fight.

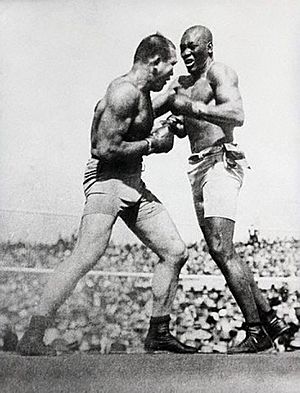

"Fight of the Century"

In 1910, former undefeated heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries came out of retirement to challenge Johnson. Jeffries said he was fighting "for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro." He hadn't fought in six years and had to lose a lot of weight to get back in shape. People wanted Jeffries to "retrieve the honor of the white race" after Johnson's win. At first, Jeffries didn't want to fight. But Johnson and Jeffries signed a deal for the fight. They knew it would make a lot of money.

Jeffries stayed out of the public eye before the fight, while Johnson enjoyed the attention. Many boxing experts thought Johnson was in much better shape than Jeffries. Before the fight, Jeffries said he would try to knock Johnson out quickly. Johnson simply said, "May the best man win." There was a lot of racial tension and gambling around the fight. Most people bet on Jeffries to win.

The fight happened on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada. About 20,000 people watched. Johnson was much stronger and faster. He completely controlled the fight. By the 15th round, Jeffries had been knocked down twice, which had never happened to him before. Jeffries' team stopped the fight to prevent him from being knocked out.

Johnson later said he knew he would win in the 4th round. He hit Jeffries with an uppercut and saw a look on his face that told him Jeffries was losing hope. After the fight, Jeffries admitted, "I could never have whipped Johnson at my best. I couldn't have hit him. No, I couldn't have reached him in 1,000 years."

The "Fight of the Century" earned Johnson $65,000, which is like millions of dollars today. This win proved that Johnson was a true champion. Famous boxer John L. Sullivan said that Johnson won fairly and clearly. He admired Johnson's skill and fair play.

Riots and Aftermath

Johnson's victory caused race riots across the United States on July 4, 1910. Many white people were angry and felt ashamed that a black man had beaten their "great white hope." Black people, however, were overjoyed. They celebrated Johnson's win as a victory for racial progress. Black poet William Waring Cuney wrote about how black people reacted to the fight. Across the country, black communities held parades and prayer meetings.

Riots broke out in many cities, including New York, Baltimore, and St. Louis. In total, riots happened in over 25 states and 50 cities.

Film of the Fight

A film of The Johnson–Jeffries Fight became very popular. It was watched by more people than any other film at the time. Many states and cities in the U.S. banned showing the film of Johnson's victory. This movement to stop the film spread quickly.

Two weeks after the fight, former President Theodore Roosevelt, who loved boxing, wrote an article. He said that films of boxing matches should be banned, and even all prize fights in the U.S. He said that boxing led to cheating and gambling. The controversy around the film led Congress to ban showing prizefight films across state lines in 1912. This ban was lifted in 1940.

In 2005, the film of the Jeffries–Johnson "Fight of the Century" was added to the United States National Film Registry. This means it was considered important enough to be saved.

Keeping the "Color Bar" in Boxing

Even after Johnson became world champion, the "color bar" (meaning black boxers were kept separate) still existed. For the first five years of his reign, Johnson did not fight any black opponents. He refused matches against talented black heavyweights like Joe Jeanette, Sam Langford, and Harry Wills.

Some people said Johnson avoided fighting black boxers because he could make more money fighting white boxers. This upset the African-American community. They felt that Johnson, as the first black world champion, should have given other black boxers a chance at the title, since opportunities to fight top white boxers were rare for them. Jeanette criticized Johnson, saying, "Jack forgot about his old friends after he became champion and drew the color line against his own people."

Johnson vs. Johnson

When Jack Johnson finally agreed to fight a black opponent in late 1913, it wasn't Sam Langford, who was the current colored heavyweight champion. Instead, Johnson chose to fight Battling Jim Johnson, a less famous boxer.

The fight was scheduled for 10 rounds on December 19, 1913, in Paris. It was the first time in history that two black boxers fought for the world heavyweight championship. However, the fight seemed more like an exhibition. A sportswriter reported that the crowd became angry because neither boxer seemed to be fighting seriously.

Jack Johnson kept his championship because the fight was a draw. After the match, he said his left arm was injured in the third round, which prevented him from using it properly.

Losing the Title

On April 5, 1915, Johnson lost his title to Jess Willard. Willard was a cowboy from Kansas who started boxing at 27. The fight took place in Havana, Cuba, in front of 25,000 people. Johnson was knocked out in the 26th round of a planned 45-round fight. Johnson had won almost every round, but he started to get tired after the 20th round. Willard hit him with heavy body punches before the knockout.

Years later, Johnson was rumored to have said he purposely lost the fight. Some thought he did this to get his Mann Act charges dropped because Willard was white. Willard joked, "If he was going to throw the fight, I wish he'd done it sooner. It was hotter than hell out there." Most people believe Willard won the fight fairly.

After His Championship

After losing his world heavyweight title, Johnson never fought for the colored heavyweight title again. He remained popular and even recorded music in the 1920s. Johnson continued to box, but he was getting older. He fought professionally until 1938, when he was 60 years old. He lost 7 of his last 9 fights. Many people think that fights after he turned 40 shouldn't really count on his record, as he was mostly fighting to earn money.

He also took part in "cellar" fighting, which were unadvertised matches for private audiences. Johnson's last time in the ring was on November 27, 1945, at age 67. He fought three one-minute exhibition rounds against two opponents, Joe Jeanette and John Ballcort, to help sell U.S. War Bonds.

Boxing Style

Jack Johnson had a unique boxing style. Unlike many boxers of his time, he often started by hitting first but then fought defensively. He would wait for his opponents to get tired. As the fight went on, he would become more aggressive. He often aimed to wear down his opponents rather than trying for a quick knockout. He was very good at dodging punches and then quickly hitting back. Johnson made his fights look easy, as if he had more energy to spare. But when he needed to, he could show powerful moves and punches. In some films of his fights, you can see him holding up an opponent who might have fallen, giving them a chance to recover.

Personal Life

Johnson earned a lot of money from promoting products. He had expensive hobbies, like car racing and buying fancy clothes, jewelry, and furs for his wives. Once, he was stopped for a $50 speeding ticket. He gave the officer a $100 bill and told him to keep the change because he was going to drive back at the same speed. In 1920, Johnson opened a nightclub in Harlem called the Club Deluxe. It was a "Black and Tan" club, meaning it welcomed both black and white customers. He sold it three years later, and it became the famous Cotton Club.

Some people in the African-American community, like scholar Booker T. Washington, did not approve of Johnson's lifestyle. Washington said it was "unfortunate that a man with money should use it in a way to injure his own people."

Johnson challenged the rules about where black people belonged in American society. He broke social rules by having relationships with white women. He also liked to verbally tease other men, both white and black, inside and outside the boxing ring. When a reporter asked him how he stayed so strong, Johnson supposedly joked, "Eat jellied eels and think distant thoughts."

In 1911, Johnson tried to join the Freemasons in Scotland. He was accepted, but there was a lot of opposition because of his race. His membership was later ruled illegal, and his fees were returned.

In July 1912, Johnson opened an interracial nightclub in Chicago called Café de Champion.

Johnson wrote two books about his life: Mes combats in 1914 and Jack Johnson in the Ring and Out in 1927.

In 1943, Johnson attended a church service in Los Angeles. During a time of race riots in Detroit, he publicly said he believed in Christ during a service led by evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson. She welcomed him as he raised his hand in worship.

Marriages

Jack Johnson was married three times. All of his wives were white. He met Etta Terry Duryea in 1909 and they married in 1911. Etta died in 1912.

In the summer of 1912, Johnson met Lucille Cameron, an 18-year-old from Minneapolis, at his nightclub. He hired her as his secretary. Soon after Etta's funeral, they were seen together as a couple. They married on December 3, 1912. Cameron filed for divorce in 1924.

Johnson met Irene Pineau in 1924. After she divorced her husband, they married in August 1925. Johnson and Pineau stayed together until his death in 1946. When a reporter asked Irene what she loved about him at his funeral, she said, "I loved him because of his courage. He faced the world unafraid. There wasn't anybody or anything he feared."

Legal Troubles and Pardon

On October 18, 1912, Johnson was arrested. The charge was that his relationship with Lucille Cameron broke the Mann Act. This law was about taking women across state lines for certain reasons. Lucille Cameron, who soon became his second wife, refused to help the police, and the case was dropped. But less than a month later, Johnson was arrested again on similar charges.

This time, a woman named Belle Schreiber, who he had known earlier, testified against him. In June 1913, Johnson was found guilty by an all-white jury. Many believed the charges were unfair because the events happened before the Mann Act was passed. He was sentenced to a year and a day in prison.

Johnson left the country before going to prison. He went to Canada and then to France. He lived outside the U.S. for seven years, fighting boxing matches in Europe, South America, and Mexico. Johnson returned to the U.S. on July 20, 1920. He turned himself in at the Mexican border and went to prison in September 1920. He was released on July 9, 1921.

Presidential Pardon

In 2018, President Donald Trump officially pardoned Johnson after many years of people asking for it. A pardon means his past conviction was forgiven. People had tried to get Johnson pardoned by previous presidents, but it didn't happen. In 2009, Senator John McCain, along with others like filmmaker Ken Burns and Johnson's great-niece, asked President Barack Obama for a pardon. Congress also passed a resolution asking Obama to pardon Johnson.

In 2016, another request for Johnson's pardon was sent to President Obama. This time, they mentioned a law that said Congress believed Johnson should get a pardon. The United States Commission on Civil Rights also voted to "right this century-old wrong."

Famous boxers like Mike Tyson and politicians like Harry Reid and John McCain supported the campaign. They started online petitions asking for the pardon.

Finally, in April 2018, President Donald Trump announced he was thinking about pardoning Johnson. He had talked with a boxing committee and actor Sylvester Stallone. Trump pardoned Johnson on May 24, 2018, 105 years after his conviction. The ceremony included special guests from the boxing world and Sylvester Stallone.

Death

On June 10, 1946, Johnson was in a car crash on U.S. Highway 1 near Franklinton, North Carolina. He had driven away angrily from a segregated diner that refused to serve him. His friend survived the crash, but Johnson was injured. He was taken to the nearest black hospital, St. Agnes Hospital, 25 miles away in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he died. He was 68 years old.

Johnson was buried next to his first wife, Etta Duryea Johnson, in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago. His grave was unmarked for a while, then had a stone with just "Johnson" on it. After Ken Burns made a film about Johnson's life in 2005, a new, smaller gravestone was added. It reads: "Jack / John A. Johnson / 1878-1946" and "First black heavyweight / champion of the world." Johnson's signature is on the back of the stone.

Legacy

Jack Johnson was one of the first people inducted into The Ring magazine's Boxing Hall of Fame in 1954. He was also inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1993. In 2005, the film of his 1910 fight with Jeffries was added to the U.S. National Film Registry because it was "historically significant."

During his boxing career, Jack Johnson fought 114 times. He won 80 matches, with 45 knockouts.

Johnson's impact on boxing was huge. He was a pioneer for future black boxers, especially Muhammad Ali. Ali often said that Jack Johnson influenced him. Ali felt that America treated him unfairly, just like Johnson, because of his opposition to the Vietnam War and his connection to the Nation of Islam.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Jack Johnson on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.

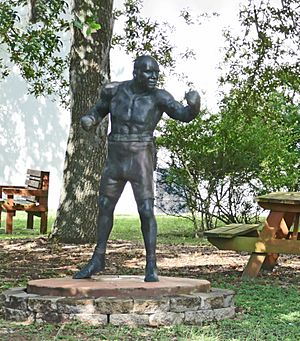

In 2012, the city of Galveston dedicated a park to Johnson. It's called Jack Johnson Park and has a life-size bronze statue of him.

In Popular Culture

- The first film about Johnson's career was The Burns-Johnson Fight in 1908.

- Folksinger Lead Belly mentioned Johnson in a song about the Titanic.

- Johnson's story is the basis for the play The Great White Hope and its 1970 film.

- In 1970, a film called Jack Johnson was made using old footage. Miles Davis created the music for it.

- In 2005, filmmaker Ken Burns made a two-part documentary about Johnson's life called Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson.

- The podcast History on Fire by historian Daniele Bolelli also told Johnson's story.

- Hip hop artists like Mos Def have honored Johnson in their music.

- During World War One, British soldiers used "Jack Johnson" to describe large, black German artillery shells.

- Artist Raymond Saunders painted Jack Johnson several times.

- In Joe R. Lansdale's 1997 short story The Big Blow, Johnson is a character fighting during the 1900 Galveston hurricane.

- The Royale, a play by Marco Ramirez, is inspired by Jack Johnson's life.

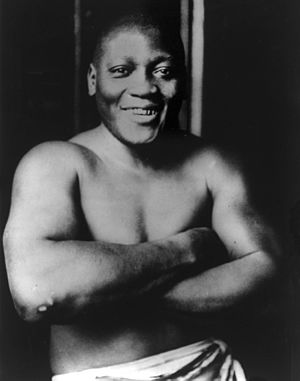

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jack Johnson (boxeador) para niños

In Spanish: Jack Johnson (boxeador) para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |