Pathé Records facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pathé Records |

|

|---|---|

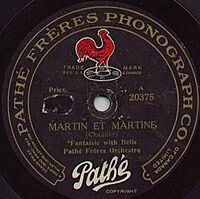

Pathé disc label

|

|

| Parent company | Pathé |

| Founded | 1890 |

| Founder | Charles Pathé Émile Pathé |

| Defunct | 1928 |

| Status | Inactive |

| Genre | Jazz |

| Country of origin | France |

| Location | Paris |

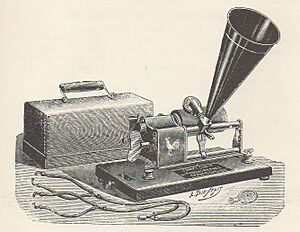

Pathé Records was a famous company from France that made and sold music records and phonographs (old-fashioned record players). They were active from the 1890s all the way through the 1930s! They became a big name in the music world.

Contents

How Pathé Records Started

The Pathé record business was started by two brothers, Charles and Émile Pathé. They used to own a popular restaurant in Paris. In the mid-1890s, they began selling phonographs and cylinder records made by other companies like Edison and Columbia.

Soon after, the brothers designed and sold their own phonographs. They also started selling their own pre-recorded cylinder records. By 1896, the Pathé brothers had offices and recording studios not just in Paris, but also in big cities like London, Milan, and St. Petersburg.

Pathé's Records: Cylinders and Discs

In 1894, the Pathé brothers began selling their own phonographs. At first, Pathé made phonograph cylinders. They kept making these cylinder records until about 1914.

Pathé made cylinders in different sizes. Besides the standard size (about 2.25 inches wide), they made larger ones. The "Salon" records were 3.5 inches wide, and the "Stentor" records were 5 inches wide. The "Le Céleste" records were the biggest commercial cylinder records ever made! They were 5 inches wide and 9 inches long.

Pathé's Disc Records

In 1905, the Pathé brothers started making disc records. These were different from other companies' records in a few ways:

- The sound was recorded "vertically" in the groove, not side-to-side.

- The groove was wider, so you needed a special ball-shaped needle to play them.

- The discs spun at 90 rpm, which was faster than the usual 75 to 80 rpm.

- Originally, the music started in the middle of the record and spiraled out to the edge.

In 1916, Pathé changed to the more common way of making records. The music started at the edge and spiraled inward. They also used a more normal speed of 80 rpm and started using paper labels instead of text stamped into the record.

Pathé discs came in many sizes, like 10, 10.5, and 11.5 inches. They also made very large 20-inch discs that played at 120 rpm! But these huge records were expensive and broke easily, so they didn't sell for long.

Pathé Records Around the World

In France, Pathé became the biggest and most successful company for cylinder records and phonographs. However, their cylinder records weren't very popular in other countries like the United Kingdom and the United States, where other brands were already well-known.

Even though their cylinders didn't do well abroad, Pathé's disc records sold successfully in many countries. These included the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and Russia.

How Pathé Made Master Recordings

Pathé was one of the first companies to record music on one type of material and then copy it to the final records. In their studios, they cut master recordings onto large, fast-spinning wax cylinders. These were called "Master Cylinders."

Later, they would copy the music from these Master Cylinders onto the different types of Pathé cylinders and discs they sold. This way, the same song could be available on many different record formats.

Playing Pathé Records

Pathé discs usually needed a special Pathé phonograph with a sapphire ball-shaped needle. The good thing about this sapphire needle was that it lasted a long time. You didn't have to change it after every record!

Since most other records and phonographs used a different way of playing, you could buy special attachments. These attachments let you play standard records on a Pathé phonograph, or play Pathé records on a regular phonograph.

New Types of Records

In 1920, Pathé started making "needle-cut" records, first for the US market. These records were made to work with standard phonographs and were called Pathé Actuelle. The next year, these "needle-cut" records came to the United Kingdom. Soon, they were selling more than the vertical-cut Pathé records, even in Europe. Pathé stopped trying to sell their vertical-cut discs outside France in 1925, but they kept selling them in France until 1932.

In mid-1922, Pathé launched a cheaper record label called Perfect. This label became very popular in the 1920s and lasted until 1938, even after the main US Pathé label stopped in 1930.

In January 1927, Pathé started using new electronic microphone technology for recording. Before this, they used a purely mechanical way to capture sound.

In December 1928, the Pathé phonograph businesses in France and Britain were sold to the British Columbia Graphophone Company. In July 1929, the American Pathé record company joined with the new American Record Corporation.

Today, the Pathé and Pathé-Marconi record labels and their music collection still exist. They were part of EMI and are now part of Parlophone Records. The film part of Pathé Frères still exists in France.

See also

- List of record labels

- Pathé News

- Pathé Pictures

- Pathé Records (Shanghai & Hong Kong)