Peshtigo fire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Peshtigo fire |

|

|---|---|

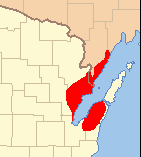

Extent of wildfire damage

|

|

| Location | Peshtigo, Wisconsin |

| Coordinates | 45°03′N 87°45′W / 45.05°N 87.75°W |

| Statistics | |

| Cost | In excess of $5 million (estimated) |

| Date(s) | October 8, 1871 |

| Burned area | 1,200,000 acres (490,000 ha) |

| Cause | Small embers from slash and burn agriculture were caught up in drafts from unusually high winds during a period of extremely dry drought-like conditions. |

| Land use | Logging Industry |

| Deaths | 1,500–2,500 (estimated) |

| Map | |

The Peshtigo fire was a huge forest fire that happened on October 8, 1871. It swept through northeastern Wisconsin, including the Door Peninsula, and parts of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin, with about 1,700 people, was the largest community affected.

This fire burned about 1.2 million acres (4,900 km²) of land. It is known as the deadliest wildfire ever recorded. Experts believe between 1,500 and 2,500 people died. The exact number is hard to know because many records were destroyed.

The Peshtigo fire happened on the same day as the more famous Great Chicago Fire. Even though the Peshtigo fire killed five times as many people, it is often forgotten. Other major fires also happened that day in Michigan, like in Holland, Manistee, and Port Huron. These fires, like many others in the 1800s, were caused by small fires combined with very dry weather.

Contents

What Caused the Peshtigo Fire?

Slash-and-burn was a common way to clear land for farming and building railroads. This method involves cutting down trees and burning the leftover wood and brush. On October 8, 1871, a cold front moved in, bringing very strong winds. These winds caused many small slash-and-burn fires to combine into one giant blaze.

The Firestorm Begins

The combined fires turned into a firestorm. A firestorm is an extremely intense fire. It creates its own wind system. It can reach temperatures of over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,093 °C). Winds inside a firestorm can blow at 110 miles per hour (177 km/h) or faster. It's like "nature's nuclear explosion."

The Peshtigo fire burned between 1.2 and 1.5 million acres of land. Besides Peshtigo, 16 other towns were completely destroyed. The fire caused about $5 million in damage. This would be hundreds of millions of dollars today. Also, millions of trees and animals died. This had a huge impact on the local economy.

Counting the Lost Lives

It's hard to know exactly how many people died. All local records were burned in the fire. Estimates range from 1,200 to 2,400 deaths. A report from 1873 listed 1,182 names of people who died or went missing. More than 350 bodies were buried in a mass grave. This was because no one was left to identify them.

A survivor named Rev. Peter Pernin wrote about the fire. He said a long period of dry weather and human carelessness led to the disaster. He also saw the fire jump across the Peshtigo River. It used bridges and strong winds to burn both sides of the town. Other survivors said the firestorm created a fire whirl. This was like a tornado made of fire. It threw rail cars and houses into the air. Many people saved themselves by jumping into the Peshtigo River or other water sources.

Another fire burned parts of the Door Peninsula at the same time. Some people thought the Peshtigo fire jumped across Green Bay. But it did not. The firestorm likely spread and started a new fire in New Franken. This fire then spread north to Sturgeon Bay.

Was a Comet Involved?

Since 1883, some people have wondered if the Peshtigo and Chicago fires were connected. They thought fragments from Biela's Comet might have caused all the major fires that day. This idea was brought up again in a book and a documentary.

Some strange things about the fires seemed to support this idea. For example, people reported seeing blue flames in basements. Some thought this was burning comet gases. However, scientists now know that blue flames can come from burning carbon monoxide in basements with poor air flow. Also, scientists say there has never been a proven case of a fire started by a meteorite.

In reality, no outside cause was needed. Many small fires were already burning in the area. These were from land-clearing activities. The summer had been very dry, making everything easy to burn. All it took was a strong wind from a weather front to turn these small fires into a huge firestorm.

What Happened After the Fire?

The Peshtigo fire is still the deadliest wildfire in U.S. history.

William B. Ogden, who owned factories in Peshtigo, helped rebuild the town. But it was a slow process. Many buildings, like the woodenware factory, never reopened. Today, Peshtigo has about 3,500 residents.

The Peshtigo Fire Museum tells the story of the fire. It has artifacts, survivor stories, and a graveyard for the victims. A memorial was put up on October 8, 2012, at the bridge over the Peshtigo River. The Peshtigo Fire Cemetery is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Chapel That Survived

The National Shrine of Our Lady of Good Help is a special place in Champion. It was built where a chapel stood during the fire. Sister Adele Brise and others took shelter there and survived. Sister Adele had a vision years before the fire. She said the Virgin Mary warned that people needed to change their ways. When the fire came, many people went to the chapel for safety. They prayed, and hours later, rain came and put out the fire.

The convent, school, chapel, and five acres of land around it were some of the few things that survived. Even animals brought to the chapel grounds were safe. People believed the Virgin Mary had saved them. Some stories of miracles at the chapel followed, but these have not been officially proven.

Tornado Memorial County Park is located where the village of Williamsonville once stood. It is named after the fire whirl that happened there. Only 19 out of 76 residents survived, and Williamsonville was never rebuilt.

Lessons Learned?

The way the land, weather, and small fires came together to create the Peshtigo fire is called the "Peshtigo paradigm." During World War II, the American and British militaries studied this fire. They wanted to learn how to create firestorms for bombing cities in Germany and Japan. They even made small models of wooden buildings to see how to drop bombs to cause a firestorm.

However, the fire did not lead to many changes in how people used forests. Logging continued, and many more large fires happened in the following decades. Wisconsin alone had major fires in 1880, 1891, 1894, 1897, 1908, 1910, 1923, 1931, and 1936. Losing half a million acres of forest each year was common.

See also

Other October 8, 1871 fires

- Great Chicago Fire

- Great Michigan Fire

- Port Huron Fire of 1871

Other fire disasters in the Great Lakes

- Great Hinckley Fire of 1894

- Baudette fire of 1910

- Cloquet fire of 1918

- Thumb Fire of 1881 (see also List of Michigan wildfires)

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |