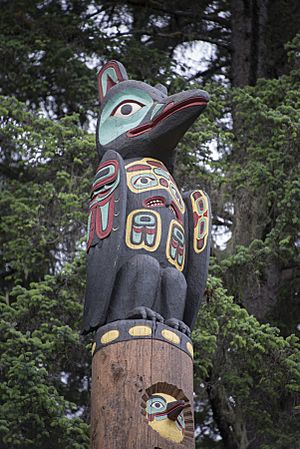

Philosophy and religion of the Tlingit facts for kids

The Tlingit people had a special way of understanding the world. Their beliefs, though not written down like a rulebook, guided how they lived and saw everything around them.

Between 1886 and 1895, many Tlingit people changed their religion to Orthodox Christianity. This happened because their traditional healers, called shamans, couldn't cure new diseases like smallpox that came from other parts of the world. Some people believe they chose Orthodox Christianity to avoid becoming too much like the "American way of life," which was linked to Presbyterianism. Russian Orthodox missionaries even translated their church services into the Tlingit language. After they became Christians, some of the old Tlingit beliefs started to fade away.

Today, some young Tlingit people are looking back at their traditional beliefs for ideas, comfort, and a stronger sense of who they are. Even though many elders became Christian, Tlingit people now often find ways to connect both Christianity and their traditional culture.

Contents

Two Sides of the World

The Tlingit people saw the world as having two main parts that were opposite but connected. The clearest example is the difference between the bright water and the dark forest that surrounded their homes in Southeast Alaska.

The water was very important for travel and for getting most of their food. The ocean surface was flat and wide, and most dangers on the water were easy to see. Light reflected brightly off the sea, making it one of the first things people saw. While dangers could hide beneath the surface, they were usually easy to avoid with care. Because of this, the water was seen as a safe and reliable place. It represented the clear and visible parts of the Tlingit world.

In contrast, the thick and mysterious rainforest of Southeast Alaska was dark and misty, even on sunny summer days. Many dangers lurked there, like bears, falling trees, muddy swamps, and the risk of getting lost. It was hard to see far in the forest, and there were few clear landmarks. Food was also much harder to find compared to the seashore. Walking in the forest usually meant going uphill on steep mountains, and clear paths were rare. So, the forest represented the hidden and mysterious forces in the Tlingit world.

Other opposite ideas in Tlingit thinking included wet versus dry, hot versus cold, and hard versus soft. A wet, cold climate made people want warm, dry shelter. The traditional Tlingit house, built from strong red cedar wood with a warm central fireplace, showed their ideal of warmth, hardness, and dryness. This was very different from the soggy forest floor, which was covered with soft, rotting trees and squishy moss, making it uncomfortable to live in.

The Tlingit valued three qualities in a person: hardness, dryness, and heat. These could be seen in many ways. For example, the hardness of strong bones or a strong will. The heat given off by a healthy person or the heat of strong feelings. And the dryness of clean skin and hair, or the sharp, dry smell of cedar wood.

Understanding Life and Spirits

The Tlingit people believed a living being had several parts:

- k̲aa daa — This is the body, the physical outside of a person.

- k̲aa daadleeyí — This means the flesh of the body.

- k̲aa ch'áatwu — This is the skin.

- k̲aa s'aaghí — These are the bones.

- x̲'aséikw — This is the vital force or breath, like the energy that keeps you alive.

- k̲aa toowú — This is the mind, thoughts, and feelings.

- k̲aa yahaayí — This is the soul or shadow, your true essence.

- k̲aa yakghwahéiyagu — This is a ghost or spirit that returns.

- s'igheekháawu — This is a ghost found in a cemetery.

The physical parts of the body, like flesh and skin, don't have a life after death. Flesh decays quickly and usually has little spiritual meaning. However, bones are very important in Tlingit spiritual beliefs. Bones are the hard and dry parts that remain after something dies. They are a physical reminder of that being.

For animals, it was very important to handle and get rid of their bones correctly. If bones were not treated with respect, the animal's spirit might be upset. This could stop the animal from being reborn. For example, a salmon that came back to life without a jaw or tail would not want to swim in the same stream again.

In humans, the backbone and the eight "long bones" of the arms and legs were especially important. The number eight was special in Tlingit culture. If a person was cremated (burned after death), their bones had to be collected and placed with those of their clan ancestors. If not, the person's spirit might be unhappy in the afterlife. This could cause problems, like the ghost haunting people, or the person not being reborn properly.

The source of life was found in xh'aséikw, the essence of life. This is similar to the Chinese idea of qi, which is a special energy needed for something to be alive. In Tlingit thought, this could also mean breath. For example, a shaman would test if someone was alive by holding a soft feather above their mouth or nose. If the feather moved, the person was breathing and alive, even if their breath couldn't be heard. This meant they still had x̲'aséikw.

A person's feelings and thoughts were part of their k̲aa toowú. This was a very basic idea in Tlingit culture. When a Tlingit person talked about their mind or feelings, they would say ax̲ toowú, meaning "my mind." So, "Ax̲ toowú yanéekw" (I am sad) literally means "My mind is pained."

Both x̲'aséikw (vital force) and k̲aa toowú (mind/feelings) were believed to end when a being died. However, the k̲aa yahaayí (soul/shadow) and k̲aa yakghwahéiyagu (ghost) were thought to be immortal. They continued to exist in different forms after death. The k̲aa yahaayí was seen as a person's true essence, shadow, or reflection. It could even refer to how a person looked in a photo or painting. It was also used to describe someone acting or looking different from who they truly were.

Life After Death

The Tlingit practice of cremation showed the importance of heat, dryness, and hardness. The body was burned, which removed all the water with great heat. Only the hard bones were left behind. The soul was believed to go near the warmth of a great bonfire in a spirit world house. If a body was not cremated, the soul would be in a cold place near the door. The hardest, most physical part of the spirit was reborn into a family member of the same clan.

Shamans and Their Powers

A shaman was called an ixht'. They were important healers and could also tell the future. People would ask them to cure the sick or to get rid of those who practiced witchcraft.

It's not quite right to call them "witch doctors" because the shaman's practices were very different from a witch's. Calling them a "medicine man" is also not correct. The Tlingit term for a "medicine master" was naak'w s'aati, which was actually their word for a witch.

The shaman's name, their songs, and the stories of their visions belonged to their clan. A shaman would seek spirit helpers from different animals. After fasting for four days, the animal would "stand up in front of him" before entering him, and he would gain its spirit. The animal's tongue would be cut out and added to the shaman's collection of spirit helpers. This is why some people called them "the spirit man."

Future shamans were sometimes chosen by the elders of a Tlingit community even before they were born. The elders believed they knew what people would become. A boy training to be a shaman would be taught how to approach graves and handle special objects. Touching shaman objects was strictly forbidden for anyone except the shaman and their helpers. In fact, the elders had a special word just for when a child tried to touch or play with a shaman's things. This word was said with a serious tone, and that was all that was needed to stop them.

Today, there are no shamans among the Tlingit people, and their specific practices will likely not be brought back. However, shaman spirit songs are still performed in ceremonies, and their stories are retold during those times.

The Mysterious Kushtakas

The Kushtaka (pronounced kû'cta-qa) are the feared Land Otter People. They are said to be human from the waist up and otter-like below. Land otters are excellent at catching fish. The Tlingit believed that people who drowned often married (and became) land otters. Land otters could also help cause drownings. They were seen as mysterious and potentially dangerous beings.

However, if they were controlled properly, the land otter could be very helpful to fishermen who went into special, sacred areas beyond normal human places. Those who drowned and married land otters (and their land otter children) could return to their human families. They would help them, usually by helping them catch lots of seafood. The land otters could only eat raw food. If they ate cooked fish, they would die. As supernatural beings, after being on the water, they had to get back to land and find shelter before the raven called, or they would die.

People who drowned and were saved by the Kushtaka were known as Kushtakakhaa. They lived with the Kushtaka, but because they were once human, they would sometimes visit their old communities. As Kushtakakhaa, they had the power to change people's minds and even change their own shape.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |