Podosphaera macularis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Podosphaera macularis |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Leotiomycetes |

| Order: | Erysiphales |

| Family: | Erysiphaceae |

| Genus: | Podosphaera |

| Species: |

P. macularis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Podosphaera macularis (Wallr.) U. Braun & S. Takam., (2000)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Alphitomorpha macularis |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Podosphaera macularis (formerly known as Sphaerotheca macularis) is a tiny plant disease, a type of fungus, that causes a problem called powdery mildew. It's like a white, dusty coating that appears on plants. This fungus can infect many different plants, including chamomile, strawberries, and especially hops.

Contents

How This Fungus Attacks Plants

The fungus that causes powdery mildew on hop plants is now called Podosphaera macularis. This fungus is known to infect only hop plants, including those grown for decoration and wild ones. Some types of hop plants are naturally strong against this fungus, like the "Nugget" variety. However, scientists have found ways for the fungus to infect even these strong plants in the lab.

When a hop plant gets sick, the first signs are yellow spots on its leaves. These spots might turn gray or white as the plant grows. You might also see white, fuzzy patches, which are actually parts of the fungus. These patches often appear on the leaves. Sometimes, the fungus can even infect the hop cones (the part of the plant used in brewing). If this happens, a brown, damaged spot might appear on the cone.

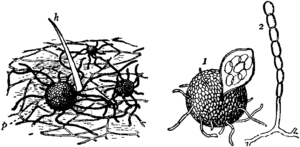

If two different types of this fungus are present, they can form tiny black dots on the underside of the leaves. These dots are called cleistothecia, and they help the fungus survive and spread.

Perfect Conditions for the Fungus

This fungus can grow very quickly. Under the right conditions, it can produce up to 20 new generations in just one growing season! The best conditions for Podosphaera macularis to grow include not too much sun, enough moisture in the soil, and a lot of plant food (fertilizer).

The fungus grows best when the temperature is between 18 and 25 degrees Celsius (about 64 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit). It also likes it when the temperature doesn't change much between night and day. For example, if it's at least 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit) at night and around 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit) during the day, the risk of infection goes up.

High humidity and the right temperature are important for the first infection, usually in late spring. During this time, the tiny black dots (cleistothecia) swell up and burst, releasing spores that start the infection. Later in the summer, from mid-July to August, other types of spores spread the disease. These spores grow best around 18 degrees Celsius (64 degrees Fahrenheit). They don't need wet leaves to grow, but light rain can help by making the air humid and reducing sunlight.

Since most of the fungus lives on the outside of the plant, very hot temperatures (over 30 degrees Celsius or 86 degrees Fahrenheit for more than three hours) and very dry air can stop it from growing or spreading. Strong rain and wind can also wash away or blow away the spores, which helps prevent the disease. Sunlight can kill the spores too, but as hop plants grow, their dense leaves can block the sun from reaching the fungus.

Its Impact on Farmers

In 1997, powdery mildew was first found in hop farms in the United States Pacific Northwest. In Washington state, this disease caused a huge loss of crops, costing farmers about $10 million. At that time, sulfur was one of the only treatments available that worked against the fungus.

By 1998, the disease had spread to Idaho and Oregon. Farmers started using methods developed in Europe to fight it. These methods included a lot of manual work, removing infected parts of plants, and using special sprays called fungicides. Even though these methods helped control the disease, they were very expensive. In 1998, it cost about $1400 per hectare (about 2.5 acres) each year to manage the disease.

In 2001, a company that buys hops refused to accept half of a special type of hop from Oregon. This was because the hop cones turned brown after being dried due to the fungus. This led to another $5 million in losses that year. These financial problems caused some hop farmers to go out of business.

Today, hop powdery mildew is still a problem every year in all hop-growing areas of the United States. While scientists are still learning more about Podosphaera macularis, the ways farmers now manage the disease have helped the hop industry recover. The amount of disease has gone down, and the cost to control it has been reduced to about $740 per hectare. This means that hop farming in the Pacific Northwest can continue to thrive. Error: no page names specified (help).

See also

In Spanish: Podosphaera macularis para niños

In Spanish: Podosphaera macularis para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |