Publication of Domesday Book facts for kids

The Domesday Book is a famous record from 1086. William the Conqueror ordered this huge survey of England. It was like a very old census and property list! Over the years, people have created many different versions of the Domesday Book. These versions help us read and understand this important historical document.

The first printed version was made by Abraham Farley in the 1770s. Later, in the 1860s, Henry James led a project to create the first exact copies, called facsimiles. These were made using a special photo process.

During the 1900s, the Victoria County History (VCH) published English translations for many counties. Then, from 1975 to 1992, the Phillimore Edition came out. This version placed the original Latin text next to an English translation. The Alecto Editions, published from 1985 to 1992, offered very high-quality facsimiles and new translations. Today, you can even find digital versions of the Domesday Book online.

Contents

Abraham Farley's First Edition (1773–1783)

In the 1700s, many people were very interested in old records. They wanted to publish histories of English counties. The Domesday Book was perfect for this. It listed properties and was arranged by county. This made it a great source for understanding the history of these areas.

The Society of Antiquaries of London wanted to publish many old records, including Domesday. They faced challenges, like not having enough money or people. But after getting a special Royal Charter in 1751, publishing Domesday seemed more possible.

In 1767, plans began for a full, scholarly edition of the Domesday Book. This was part of a bigger plan to publish other important public records.

Charles Morton, a librarian, was first put in charge in March 1767. But Abraham Farley, who worked at the Exchequer, felt he should lead the project. Farley had managed access to the Domesday Book for many years. He also helped with other record printing projects.

Farley complained to the government that he should be in charge. Morton, in turn, said that staff were making his work difficult. The government also worried about the rising costs. By 1770, Morton had spent a lot of money and needed more.

So, Farley was brought in as a co-editor. But the two men did not get along. After 1774, Farley was mostly in charge by himself.

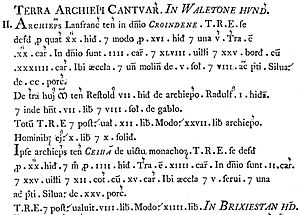

Farley worked very hard on the project. He had a strong connection to public records, especially the Domesday Book. His close friend, John Nichols, helped him. Nichols developed a special "record type" font. This font made the printed edition look as much like the original Domesday Book writing as possible. Farley's edition was finished by March 15, 1783.

Farley's work was very good, but it didn't include extra materials or indexes. So, in 1800, the Record Commission ordered indexes to be made. These were put together by Sir Henry Ellis and published in 1816. They also included four other important surveys from that time.

The Photozincographic Edition (1861–1863)

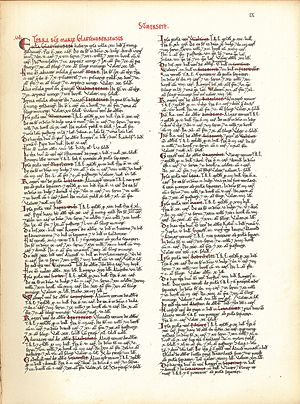

Farley's edition didn't make the Domesday Book widely available. That changed in 1861 with the first photozincographic facsimile edition. A facsimile is an exact copy.

Colonel Henry James, who led the Ordnance Survey, was the main person behind this project. The photozincography process involved taking a photograph and transferring it onto a zinc plate. This plate could then be used for printing. It was a way to make many exact copies.

In 1859, James met with William Ewart Gladstone, who was in charge of the country's money. Gladstone asked if James knew a way to copy old manuscripts. James explained that photozincography was better than other methods, like lithography. He said it would be perfect for making cheap copies of the Domesday Book.

In 1860, James estimated that 500 copies of the entire Domesday Book would cost about £1575. He also showed how affordable it was for a single county. As a test, James was allowed to copy the Cornwall section of Domesday Book in 1861. The test was a success! By 1863, the Ordnance Survey had copied the entire Domesday Book. It was published in 32 county volumes. The copies used red and black ink, just like the original manuscript.

People were very excited about this new invention. Newspapers reported on photozincography and even showed examples of documents copied with the process.

English Translations

Victoria County History (1900–1969)

The Victoria County History (VCH) started in 1899. Its goal was to publish a detailed history of each historic county in England. From the beginning, they planned to include English translations of the Domesday Book sections for each county. These would come with a scholarly introduction and a map.

J. H. Round was chosen to edit the Domesday sections. He translated texts and wrote introductions for several counties. He also oversaw work by other translators. Round retired from the project in 1908.

The VCH continued to publish Domesday translations for many more counties over the years. By 1969, most counties had a VCH translation. Only Gloucestershire was left without a published 20th-century translation from this project.

The Phillimore Edition (1975–1992)

The Phillimore Edition is a special version of the Domesday Book. It shows the original Latin text on the left page and an English translation on the right. It was published by Phillimore & Co. John Morris was the main editor. Each county had its own separate book. The first books came out in 1975, and the last ones in 1986.

The Latin text in this edition is a copy of Farley's earlier printed version. The English translation was done by a team of volunteers. They followed strict rules to make sure the language and terms were consistent. Each book also included notes, lists of names, and a map.

A guide to the Domesday Book, written by Rex Welldon Finn, was published in 1973. A set of indexes for the Phillimore Edition came out in 1992.

This edition quickly became very popular and easy to find. However, some scholars felt the translation made complex historical ideas too simple.

The Alecto Editions (1985–1992)

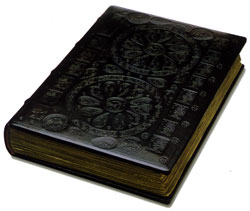

Published between 1985 and 1992, the Alecto Edition is the most complete exact copy (facsimile) of the Domesday Book made so far. There are three types: the "Penny Edition," the Millennium Edition, and the Domesday Book Studies edition. Professor Geoffrey Martin, who was in charge of the original Domesday, called it an "indecently exact facsimile."

This edition also came with an index book, a two-volume English translation, and a set of maps. These maps showed Domesday sites on modern maps.

Facsimile

To make such a high-quality copy, the original Domesday Book was carefully unbound. This allowed each page to be photographed separately. The camera used was huge, about the size of a small car! For safety, it was operated inside a sealed cage.

The Penny Edition was printed on special paper made from cotton. This paper was chosen to feel like the original parchment. The pages were then bound between pieces of 15th-century oak wood. Each book had a silver penny from William I and a special 1986 Elizabeth II penny on its cover. Because of the high cost, each Penny Edition cost £5750, and only 250 were made.

The later Millennium Edition used the same high-quality images and paper. It was bound in two calfskin volumes, similar to how books were bound in the 1100s. This edition was limited to 450 copies.

The Library Version of Domesday used the same paper but had a linen cover for durability. This version also came with indexes, translations, and maps.

Translation

The Alecto Historical Editions translation was published in two books alongside the facsimile. It aimed to be better than the VCH translation. The VCH translation, while good, had some inconsistencies because it was published over 80 years.

A team of experts worked on the Alecto translation. They made sure it was very consistent and corrected. Penguin Books later reprinted the Alecto translation in a single book. It came out in hardback in 2002 and paperback in 2003. This was the first time the Domesday Book translation was published in one volume without the Latin text.

Digital Editions

The Domesday Explorer

The Domesday Explorer was first started by John Palmer and his son Matthew Palmer in 1986. It began as a private project. Later, it received funding and was published on CD-ROM in 2000. Since 2008, it has been available online through the University of Essex.

This digital database includes high-resolution images of the original manuscript pages. It also has the text of the Phillimore translation. You can use it to map searches, see charts of reported livestock, and get statistics for each county.

Commercial Copies

You can also find commercial copies of the Domesday Book:

- The National Archives in London (nationalarchives.gov.uk) offers PDF files of any page for a fee.

- Domesdayextracts.co.uk provides six-page extracts for specific towns or villages.

See also

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |