Rewi Alley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rewi Alley

QSO MM

|

|

|---|---|

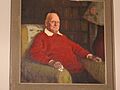

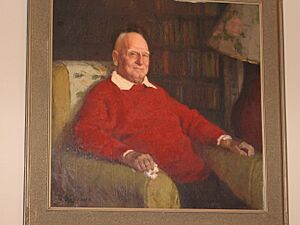

Portrait of Rewi Alley by Deng Bangzhen. Located in CPAFFC offices, Factory Street, Dongcheng District, Beijing. Once in the Italian Embassy, later in Rewi Alley's residence.

|

|

| Born | 2 December 1897 Springfield, New Zealand

|

| Died | 27 December 1987 (aged 90) Beijing, China

|

Rewi Alley was a famous New Zealander who spent 60 years of his life helping people in China. He was born in New Zealand in 1897 and passed away in China in 1987. In China, he was known as Lùyì Aìlí.

Rewi was a writer and a political activist. This means he worked to bring about social and political change. He became a member of the Chinese Communist Party, a political group that aimed to create a communist society in China. He played a big part in setting up special factories called Chinese Industrial Cooperatives and schools like the Peili Vocational Institute (also known as Bailie Vocational Institute or Beijing Bailie University). These places helped train people and create jobs. Rewi Alley wrote many books about China in the 1900s, especially about the big changes happening there. He also translated many Chinese poems into English.

Contents

Rewi's Early Life and Family

Rewi Alley was born in a small town called Springfield in New Zealand. He was named after Rewi Maniapoto, a brave Māori chief who fought against the British army in the 1860s.

Rewi's father was a teacher, and his mother, Clara, was a leader in the movement that fought for women to have the right to vote in New Zealand. Their strong interest in helping society and in education influenced all their children:

- His brother, Geoff, became a famous rugby player (an All Black) and later New Zealand's first National Librarian.

- His sister, Gwendolen (Gwen Somerset), was a pioneer in early childhood education.

- His younger sister, Joyce, became an important nursing leader.

- His brother, Philip, was a university lecturer in engineering.

In 1916, Rewi joined the New Zealand Army and went to fight in France during World War I. He won a special award called the Military Medal for his bravery. While in France, he met Chinese workers who were helping the Allied armies. After the war, he tried farming in New Zealand for a while.

Moving to China and Helping Others

In 1927, Rewi decided to move to Shanghai, China. He first thought about joining the police, but instead, he became a fire officer and then a factory inspector. This job showed him how much poverty there was in China and how some Westerners treated Chinese people unfairly.

He joined a group that studied politics and social issues. This made him think more about helping people. A terrible famine in 1929 made him realize how much the people in Chinese villages were suffering. He used his holidays to travel around rural China and help with relief efforts. In 1929, he adopted a 14-year-old Chinese boy named Duan Si Mou, whom he called Alan.

After a short visit back to New Zealand, where Alan faced racism, Rewi became the Chief Factory Inspector in Shanghai in 1932. By this time, he was secretly a member of the Chinese Communist Party. He adopted another Chinese son, Li Xue, whom he called Mike, in 1932.

When war broke out with Japan in 1937, Rewi Alley started the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives. These were small factories run by groups of people working together, often in rural areas, to produce goods needed for the war effort and daily life. He also started schools, which he named Bailie Schools after his American friend Joseph Bailie. A famous writer, Edgar Snow, said that Rewi Alley brought "guerrilla industry" to China, meaning he helped set up small, flexible industries that could operate even during wartime.

In 1945, he became the headmaster of the Shandan Bailie School after the previous head, George Hogg, passed away.

Life After the Communist Victory

After the Chinese Communist Party won the civil war in 1949, Rewi Alley was asked to stay in China and continue his work. He wrote many books and articles praising the new government of the People's Republic of China. Even when he faced difficulties during the Cultural Revolution (a period of social and political upheaval in China), he remained dedicated to his beliefs and held no hard feelings.

Rewi Alley was able to travel around the world, often giving talks about the importance of stopping nuclear weapons. The New Zealand government was proud of his connections with important Chinese leaders. In the 1950s, he was offered a special honor (a knighthood) but turned it down. He also supported North Vietnam during the Vietnam War. In 1985, he received another honor from New Zealand, the Queen's Service Order. At the ceremony, New Zealand's Prime Minister, David Lange, called him "our greatest son."

Rewi's Death and Lasting Impact

Rewi Alley passed away in Beijing on December 27, 1987. Just weeks before his death, New Zealand's Prime Minister, David Lange, spoke highly of him on his 90th birthday.

Rewi Alley's former home in Beijing is now used by the Chinese People's Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries.

There are several places that remember Rewi Alley:

Memorials to Rewi Alley

Springfield Memorial

In his hometown of Springfield, New Zealand, there is a large memorial dedicated to Rewi Alley. It includes a stone carving and panels that tell the story of his life.

Lanzhou City University Memorial Hall

In 2017, a three-story building called the Rewi Alley Memorial Building was opened at Lanzhou City University in China. It's a free museum that shows Rewi Alley's history and how much he helped China as an educator and a friend to other countries.

Shandan Memorial House

In Shandan, China, there is a replica of the house where Rewi Alley lived when he was the headmaster of the original Bailie School. It shows some of his belongings, like his bed, typewriter, and books, giving a glimpse into school life in the 1940s.

Rewi's Thoughts on China and New Zealand

Rewi Alley often shared his deep feelings about both his birth country, New Zealand, and his adopted country, China.

He believed that to truly understand China, one needed to be among its ordinary people. He recognized that China's journey to become free from foreign control and its past problems came at a huge cost. He felt that Western countries should appreciate China's fight during World War II, saying that without China's resistance, Japan might have reached Australia and New Zealand.

Rewi chose to support China's struggle. He saw China as his family and felt a strong loyalty to it, even though he knew it had its own challenges. He said that his experiences in China, especially seeing the endurance of Chinese laborers during World War I, made him want to help the country. He felt he owed China something for the important lessons he learned there.

He always considered himself a New Zealander, even if some in New Zealand didn't see him that way. He loved New Zealand and believed its people were generally fair and practical. However, he also saw a "fascist streak" in New Zealand, remembering a time when police on horseback attacked unarmed workers. He vowed to stand up against such unfairness. He knew some New Zealanders saw him as a "traitor" for his communist views, but he believed he had only betrayed their idea of what a Kiwi should be, not New Zealand itself. He always loved his home country.

Rewi's Writings

Rewi Alley said that writing was his way of helping people understand what was happening in China. He felt he had to share his experiences. He admitted he wasn't a perfect writer or poet, but it was his important work.

Poetry Collections

- Peace Through the Ages, Translations from the Poets of China, 1954

- The People Speak Out: Translations of Poems And Songs of the People of China, 1954

- Fragments of Living Peking and Other Poems, 1955

- Beyond the Withered Oak Ten Thousand Saplings Grow, 1957

- Human China, 1957

- Journey to Outer Mongolia: A Diary with Poems, 1957

- The People Sing, 1958

- Poems of Revolt, 1962

- Tu Fu: Selected Poems, 1962

- Poems of Protest, 1968

- Poems for Aotearoa, 1972

- Over China's Hills of Blue: Unpublished Poems and New Poems, 1974

- Today and Tomorrow, 1975

- Snow over the Pines, 1977

- The Freshening Breeze, 1977

- Li Pai: 200 Selected Poems, 1980

- Folk Poems from China's Minorities, 1982

- Pai Chu-i:Selected Poems, 1983

- Light and Shadow along a Great Road – An Anthology of Modern Chinese Poetry, 1984

Other Books

- Gung Ho, 1948

- Leaves from a Sandan Notebook, 1950

- Yo Banfa! (We Have a Way!), 1952

- The People Have Strength, 1954

- Man Against Flood – A Story of the 1954 Flood on the Yangtse and of the Reconstruction That Followed It, 1956

- Sandan: An Adventure in Creative Education, 1959

- China's Hinterland – in the Great Leap Forward, 1961

- Travels in China: 1966–71, 1973

- Prisoners: Shanghai 1936, 1973

- Refugees from Viet Nam in China, 1980

- Six Americans in China, 1985

- At 90: Memoirs of my China Years, 1986

- Rewi Alley, An Autobiography, 1987

Images for kids